The growing number of victims in southern and eastern Ukraine — including Friday's tragedy in Odessa that resulted in at least 46 dead — indicate that the political crisis has grown into a social and humanitarian one. The upheaval in Ukraine — and Russia's reaction to it — is the delayed consequences of the collapse of the Soviet empire and the remnants of the Soviet mindset.

The Soviet collapse in 1991 was largely a peaceful event for Russia and Ukraine, the largest of the former Soviet republics. While the bloody, armed conflicts in Abkhazia, Tajikistan, Nagorno-Karabakh and the self-proclaimed Transdnestr republic destabilized these regions, they did not touch Russia directly. Even the two Chechen wars were not considered by many Russians to be an internal conflict in the strict sense of the word, although they took place on Russian territory.

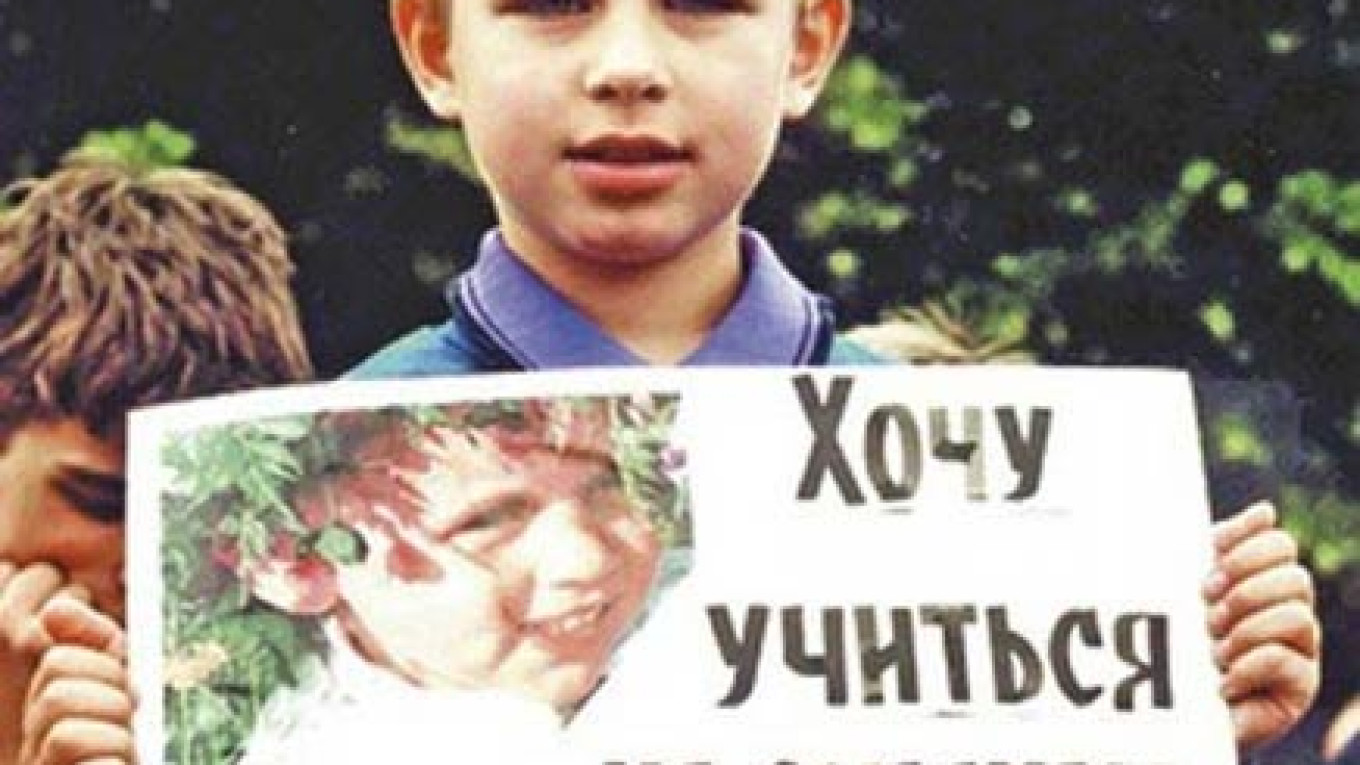

Ukraine received its independence in 1991 without any blood being spilled, but it had its share of serious economic and social problems over the past 23 years. In February, Ukrainians finally lost patience after two decades of enduring one incompetent and corrupt regime after another. It turns out that the desire for revolution was never fully overcome but only put on hold.

The acute crisis in Ukraine will force the authorities in Kiev and Ukrainians to confront a number of fundamental questions:

Will Ukraine align itself with Europe or Russia?

Will it enjoy real sovereignty or have to depend on a Big Brother?

Can the country unite on the basis of a new national identity, or will it break apart as a result of an attempt to institute "federalization" in the pro-Russian eastern and southern regions?

Crimea had been part of pre-revolutionary Russia — part of the territory won by Catherine the Great's imperial conquest in the 18th century. Then, Crimea was transferred to Ukraine during the Soviet era. President Vladimir Putin likely views the annexation of Crimea as a symbolic link with Russia's glorious imperial history, including the "Soviet empire."

Many believe that Russians can have no other identity other than as former Soviet citizens. We can assume that the Kremlin's frequent references to a larger "Russian world" ? — one consisting of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers located within and outside of Russia — is intended to renew that aging Soviet identity.

Putin's notion of a developing a broad-based "Russian world" extends beyond Russia's borders. After all, millions of ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers are concentrated in the former Soviet republics. But developing the "Russian world" necessarily contradicts the interests of neighboring nations, which will not want to sacrifice their territory — or citizens — to serve Russia's interests.

Twenty-two years ago, another federation collapsed that had been held together by a common ideology and geopolitical factors. The resulting war turned out to be the most destructive armed confrontation in post-World War II Europe. The Bosnian war was caused by the destruction of a multi-ethnic state. As a result, the Serbian people found themselves divided by the borders of the newly formed states.

In that conflict, the refusal to reject old patterns of behavior in the face of the new reality came at the cost of tens of thousands of lives and millions of refugees.

This article appeared as an editorial in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.