Will Russia plunge into chaos and darkness after President Vladimir Putin leaves? While it's understandable that propaganda-brainwashed Russians might truly think so, it comes as a surprise when U.S. analysts repeat the same idea.

"Knowing the weakness of the liberal opposition and the strength of Putin's security apparatus, it's hard not to fear that his replacement will make us long for the days of his thuggishly predictable unpredictability," warns Julia Ioffe on The New Republic. "If the U.S. gets rid of Putin they will have no ability to control what happens next," threatens Mark Adomanis on Forbes.

Such pessimistic estimates, however, are hardly well grounded. Russia's 140 million citizens should be capable of replacing their president with someone who isn't living "in another world," as German Chancellor Angela Merkel said of Putin.

The analysts who are scared of post-Putin Russia usually raise the following points: 1) Putin ruined all independent institutions and made himself the only arbiter of power. This will lead to chaos once he leaves the Kremlin. 2) Putin is the only constraint on Russia's highly motivated and organized nationalists, who will transform the country into a fascist regime once he leaves. 3) Personalistic regimes are rarely followed by democratic systems, so what's the point of replacing apples with apples?

Let's consider those arguments step by step.

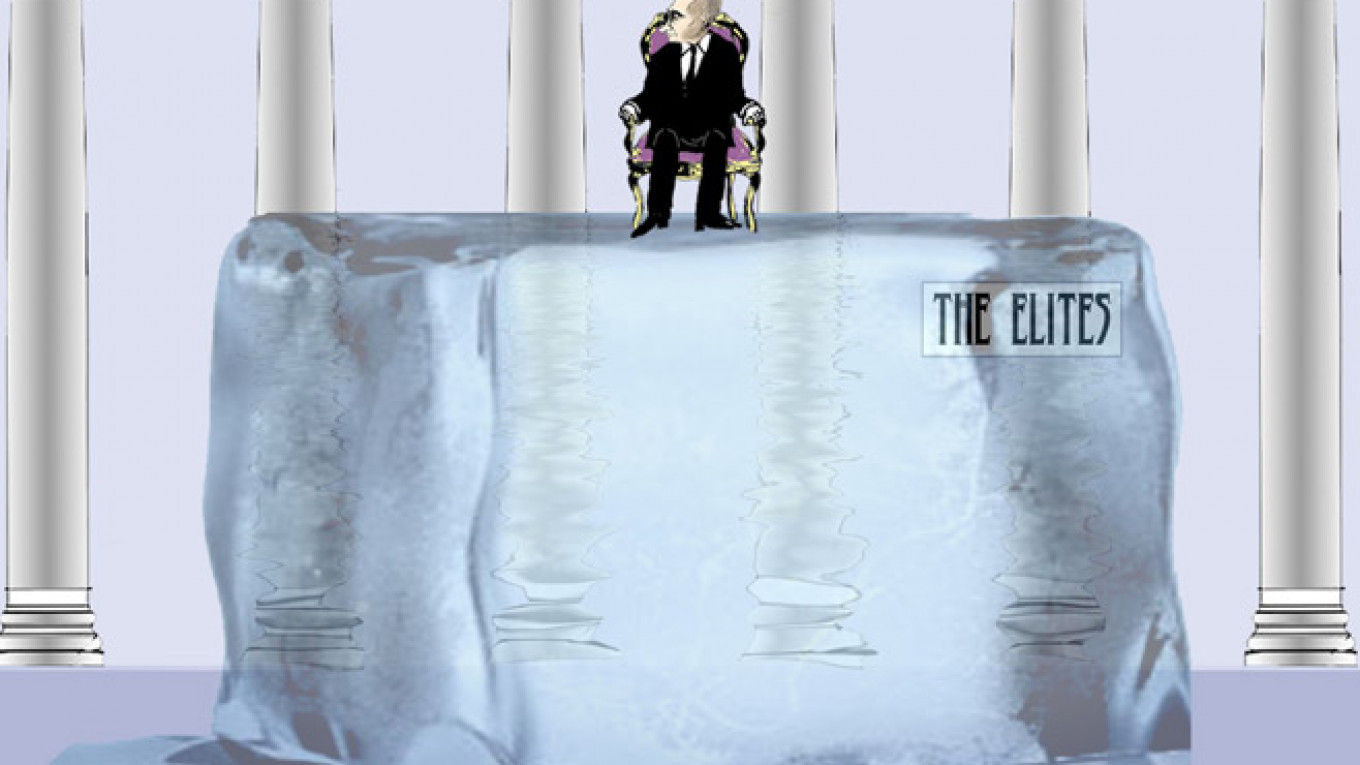

First, it's true that Putin has successfully set up an autocratic political system over the last 15 years. By destroying opposition parties, putting their leaders under arrest and blocking popular mobilization, the Kremlin has succeeded in limiting the Russian population's interest in politics. The resulting void between the authorities and the people has led to complete alienation between the elites and the masses.

But Russia would not be lost to chaos if Putin disappeared. Instead, it would empower one of the more politically successful segments in Russian society today: the liberal white-collar opposition movement. No other social group in the last 20 years has been remotely able to mobilize 100,000 to 200,000 protest participants (as they managed in 2011-12 protests), or the 630,000 Muscovites who voted for opposition candidate Alexei Navalny during last year's election for Moscow mayor.

The very demobilization of most of Russian society is also a guarantee against the emergence of nationalistic groups. Many Russians might repeat certain ideas they hear on the television, but they won't stand up for those ideas. The swings in Russian's public opinion on the major issues prove that point. For example, the support for military invasion in Ukraine dropped 20 percent from February to June following the softening of the media propaganda discourse.

Second, the threat of nationalists rising to power is over-exaggerated. Analysts argue, for instance, that the Russian public's support for eastern Ukrainian separatists is evidence of a rising tide of radical nationalist sentiment. In private conversations, however, even nationalists express doubts that a rebel defeat would lead to public backlash in Russia. The passivity and amorphousness of the post-Soviet population prevents nationalist mobilization in Russia.

And although Russians strongly support the idea of "Russia for the Russians," they are not opposed to this being moderated by civilized democratic institutions. The rise in nationalistic feelings is in large part due to huge illegal immigration from Central Asia, which in combination with poor policing has led to a surge in ethnic tensions. But a democratic solution provided by Navalny — introducing immigration visas with Central Asia — gathered substantive support in Moscow during last year's mayoral election. No radical nationalist has ever enjoyed a remotely comparable level of support in today's Russia.

Third, it is true that personalistic dictatorships like Putin's lack mechanisms for transferring power into democratic hands. But that doesn't mean the next government will be the same or even worse.

Take Ceausescu's Romania, for example. When Romania's severe Stalinist autocracy suddenly collapsed in 1989 (as a result of an elite split supported by a popular movement), it did not immediately result in democracy. But it laid the groundwork, and today Romania is an imperfect but a stable and relatively free democracy. There is no reason to assume that after Putin comes the deluge.

And although personalistic systems are hard to break, they are vulnerable to external shocks. Bad economic conditions particularly threaten them because the incumbents are thus deprived of the resources used to buy the loyalty of elites and constituencies.

Interestingly, the fragmentation process seems already to have started within the Russian elite. Last week Deputy Economic Development Minister Sergei Belyakov apologized on Facebook for a recent government decision to prop up the state budget using pension money. Although Belyakov was dismissed from the government the next day, the event itself rocked the Russian blogosphere, which had never before seen a high-ranking minister apologize to the people.

Finally, on Aug. 11, Novaya Gazeta — one of the very few remaining independent Russian newspapers — published a leaked private discussion among high-ranking Russian officials, ministers and oligarchs. The participants debated whether to accept Crimean football teams into Russia's league, and how to achieve that without provoking sanctions against them personally.

Despite expressing their loyalty for "Putin's decisions," some of the oligarchs showed strong dissatisfaction with decisions made by the Russian authorities and the resulting losses in their incomes and asset value. It is noteworthy that the sanctions, which have only been in place for a few months, have already led to substantial tensions within pro-Kremlin circles.

If the current trend continues, a potential power change might go as follows:

The tensions and dissatisfaction among pro-Kremlin elites will increase, followed by new mobilization of the Russian white-collar class (the social stratum most strongly hit by the sanctions and Putin's own recent food ban).

Once the discontented elites observe a severe level of unrest among the general population, they will start uniting and promoting their political candidates on different levels of Russia's political system: mayors, governors, local parliaments, etc.

As Putin continues to lose his popularity along with political support from different levels of Russian society, the elites will come up with an alternative candidacy that allows for a compromise between Russian business, soft-liners and the West (such as, for example, former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin). Of course, given the cowardice and weakness of dissent within pro-Kremlin elites, the process is likely to develop very slowly and gradually. But the above description provides a less gloomy scenario of future power transfer in Russia.

And there is one more reason we should be comfortable with a change in Russia's leadership. The very nature of personalistic dictatorships means that personality matters a whole lot. And so even if Russia is ruled by yet another autocrat, that ruler is unlikely to have Putin's unique disregard for the pre-existing world order.

Maria Snegovaya is a Ph.D. student at Columbia University and a columnist at Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.