But his father's bedtime stories about the apocryphal relative resurfaced when Tchalenko unearthed a 1903 telegram sent by his great-uncle, an officer in Tsar Nicholas II's army, that would help him piece together a mysterious chapter of his family history.

Now, Tchalenko -- a London-based earthquake geologist descended from emigres who fled Russia after the Revolution -- has told that story in a forthcoming book about his great-uncle, Alexander Iyas. Compiled from dozens of previously unpublished dispatches and photographs, the book paints a portrait of an earnest and humane officer caught up in the so-called "Great Game," the imperialist struggle between Russia and Britain for control of Central Asia.

Iyas, a Finnish linguist, was assigned in 1901 to the Persian outpost of Turbat and charged with checking passing caravans for signs of plague. The British, however, suspected him of reconnoitering. Whether or not he was a spy, Iyas fixed his eye on more than unseemly corpuscles during his stay in Persia: He brought with him a new-model Kodak Panoram camera, and in addition to photographing the village women, camel caravans and servants who populated his life, he also sent diligent dispatches back to St. Petersburg.

It was one such dispatch that reacquainted Tchalenko with the man his father had called "Uncle Alex."

After an earthquake shook Persia in 1903, Iyas wrote up a description of the event for his superiors in the Russian capital. The British intercepted the telegram, redirecting it to London.

Sixty-five years later, Tchalenko was studying another earthquake in the region. After a trip to Iran, he was combing through accounts of past tectonic activity when he came across Iyas' report in the archives of the British Foreign Office in London. Tchalenko's father had never talked much about his family, and the name Alexander Iyas meant nothing to the scientist. But the detail and accuracy of the telegram -- with its place names and numbers of casualties -- stuck with him.

A 1973 earthquake brought Tchalenko back to Iran, this time near the Turkish border. While reading reports on earlier earthquakes, he found a newspaper clipping about the 1914 death of Iyas, then the Russian consul in the nearby town of Soujbulak. Iyas had been beheaded by a band of Ottoman Kurds, his head piked and displayed by his killers.

Tchalenko immediately knew the consul was his Uncle Alex.

"It was that he had been not simply beheaded, but that his head had been placed on a lance before an invading army," Tchalenko said last week, speaking by telephone from France. "I put two and two together and called my father in Beirut."

Tchalenko's father, an archaeologist based in Lebanon, could not be reached due to the civil war raging in the country at the time. So Tchalenko called his father's relatives in Helsinki. They confirmed that Iyas and Uncle Alex were indeed the same man, and they quickly sent a parcel of the consul's things "that they were happy to get rid of." Among the dusty icons and medals were 300 photographic negatives. These were to become the backbone of Tchalenko's book, "Images From the Endgame: Persia Through a Russian Lens 1901-1914."

Saqi Books Iyas trained his camera at this encampment, located in what is now northwestern Iran, in the summer of 1914. | |

The exact circumstances of Iyas' death will probably never be known, but what is certain is that Ottoman Turkish troops, in league with Kurdish fighters, captured Soujbulak in December 1914. Shortly afterward, Iyas was beheaded.

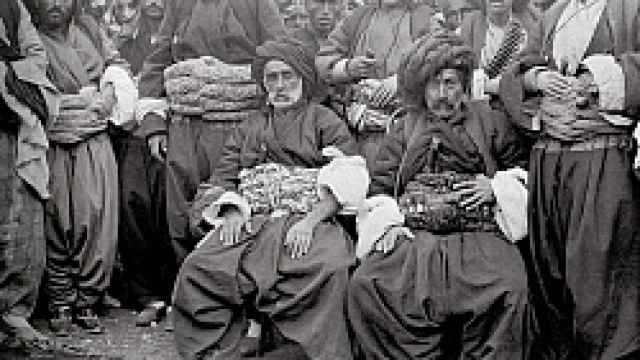

Tchalenko speculated that the killers might have had dealings with Iyas before the attack on Soujbulak that led to his death. In August 1913, Iyas had photographed the nervous-looking leader of the Kurdish Piran tribe with an army of Kurdish Mangur men arrayed behind him. The two tribes had been skirmishing, and Iyas had brokered a truce. Did these warriors, grimacing and ill at ease before Iyas' camera, turn and kill the man they had trusted enough to bring in as a negotiator?

After uncovering the photo, Tchalenko and a translator had argued about the spelling of the name of the Mangur chief (it ended up as Bayz Pasha Mangur). On a lark, Tchalenko huffily ran a Google search on "Mangur" and found the tribe's official web site.

He was able to locate Bayz's great-grandson, who lives in exile in Britain with his daughters, a doctor and psychiatrist. Tchalenko and the Mangur scion -- both displaced from their ancestral homelands -- met at a London cafe.

"I told him, 'You guys participated in the beheading of my great-uncle,'" Tchalenko recounted. "We got that out of the way at the start."

But reconciling blood grudges with ancient enemies was a simple matter compared with gaining access to the archives of the Russian Foreign Ministry. When Tchalenko tried in 2002 to find his relative's files at the ministry, he hit a brick wall.

"Nobody like that exists," came the reply. Tchalenko had to point to footnotes citing Iyas' telegrams in Mikhail Lazarev's book "The Kurdish Question (1891-1917)" before the ministry allowed him in.

Once given the run of Iyas' dispatches, Tchalenko learned that the consul was not afraid to take a stance against the slash-and-burn imperialism of the Russians.

Although Russia was allied with Persia, Iyas praised the ability of their Turkish enemies in ruling the border region: "Since the Turkish withdrawal, the order they introduced has vanished, only to be replaced by the usual attributes of any Persian administration: inertia, indifference, folly and helplessness."

Saqi Books Iyas took this photo of two Kurdish leaders in August 1913, just after negotiating a truce between their skirmishing tribes. | |

Iyas' honesty is reflected in his photography as well as his letters. Rather than pose his subjects in a studio or romanticize their otherness, Iyas walked about the markets, fields and deserts and captured what he saw.

A photograph from the winter of 1913-14 shows three men and a child walking along a muddy path in Soujbulak. One of the men adjusts his cloth belt, looking down while the others press on. Other photographs show servants, traders, foreign missionaries or local hunters proudly carrying their falcons.

Tchalenko likened Iyas' approach to that which his son, Luke -- a photographer and a former Moscow Times staff member -- displayed when on assignment in Beslan after the siege of School No. 1. "Luke photographed people in their houses, just as they were. With Iyas as well, there's an empathy with the subject," he said.

Today, the corners of present-day Iran and Iraq where Iyas took his photographs are once again commanding the world's attention. Tchalenko believes his great-uncle's example could well contain a lesson for soldiers, diplomats and policymakers in the 21st century.

"It's important not to defend to the hilt what is being done in the name of your country," he said, "but to ask what you actually think about it."

"Images From the Endgame: Persia Through a Russian Lens 1901-1914" is to be published in Britain by Saqi Books later this month.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.