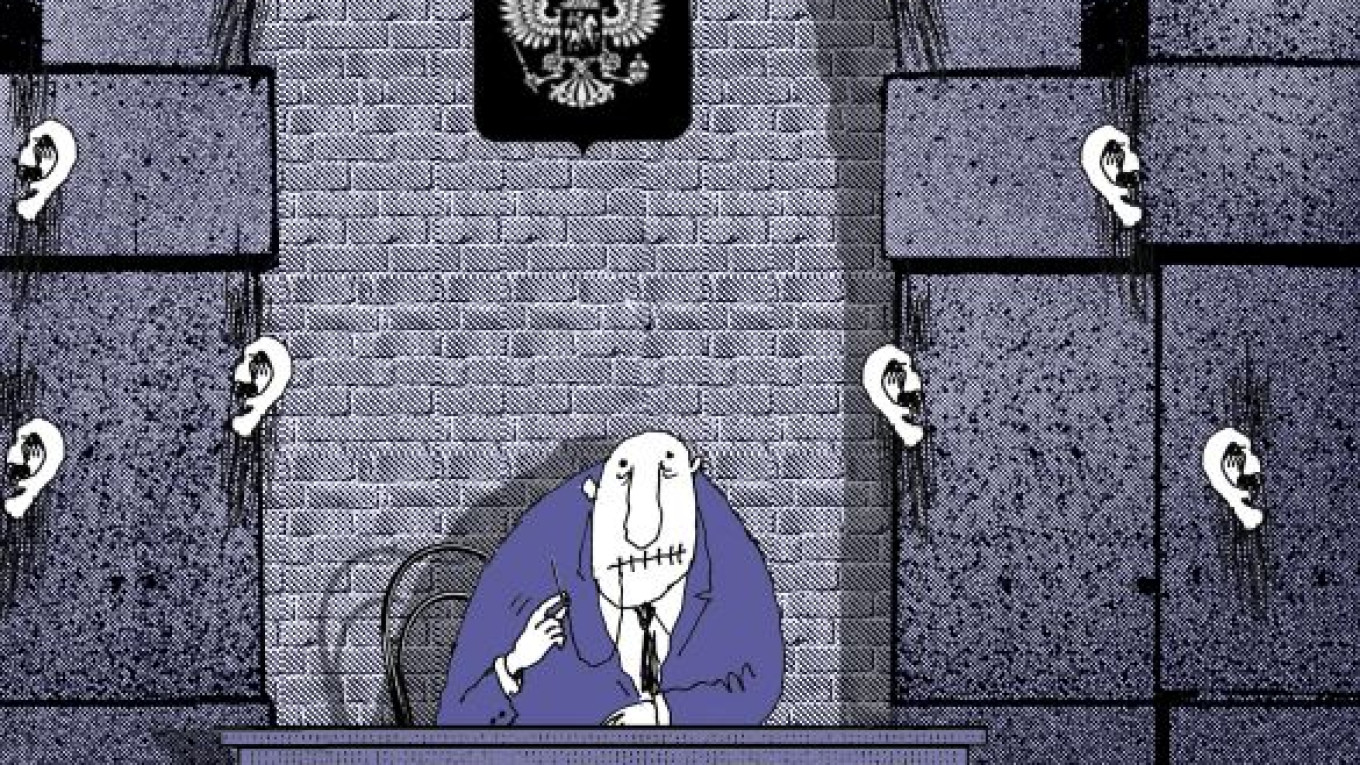

The primary goal of the recent State Duma bill that expands the definition of treason is political. As with the other repressive laws passed this summer and fall, Russians have begun feeling the heavy impact of the treason bill even before it has become a law.

The Federal Security Service has kept a typically low profile until recently, deliberately staying in the shadows of the Investigative Committee and Interior Ministry. This behavior is inconsistent with the "new nobility" status that the agency held throughout the 2000s.

Meanwhile, the opposition, which had preferred to stage pickets outside the offices of the Investigative Committee, switched to picketing FSB headquarters on Lubyanka after the anti-opposition film "Anatomy of a Protest 2" was broadcast on NTV, opposition figure Sergei Udaltsov was charged with trying to organize mass riots and opposition activist Leonid Razvozzhayev was abducted in Kiev.

As a result, rumors began circulating at Lubyanka that President Vladimir Putin had made several critical comments about the effectiveness of the work of the country's main intelligence agency. For example, when FSB generals met with Putin at the Kremlin on July 18, Putin made a direct demand that the FSB "deal in a timely manner with attempts to destabilize the social and political situation in the country."

After this comment, many at Lubyanka thought that recently announced personnel cuts at the FSB might reflect the Kremlin’s discontent with the intelligence agency's passivity. But by mid-?September, the FSB had come up with a response to the president's criticism that deployed the tactics that have served the agency so well over the past 12 years: The FSB demanded new powers by reviving a treason law that was shelved four years ago.

The bill contains two major new features: It significantly increases the number of people who could be considered a traitor under the Criminal Code, and it gives the intelligence agency the right to conduct surveillance on them indefinitely.

The bill also expands the definition of treason to mean "providing consulting or other types of work to a foreign state, foreign or international organization" if that organization acts against Russia's security interests.

In addition, treason charges can be used not only against those who reveal state secrets, but also against journalists, nongovernmental organizations and anyone else who receive "secret" information from any source.

Another dangerous feature of the bill allows for "counterintelligence operations," including covert searches, surveillance and wiretapping, which can be used against any person suspected of giving or receiving secret information. What's more, these operations can be carried out indefinitely.

In Russia, treason always has been more of an ideological than a legal concept, a leftover from the Soviet-era Criminal Code. Now, even before charges have been filed against a single individual, the legislation is helping the Kremlin bring a new chill of fear over the entire country.

Just as with the law requiring NGOs to register as "foreign agents," the loose definition of treason means that virtually anyone the authorities want to punish can fall under this legislation. As a result, consultants, members of NGOs, scientists, professors and journalists have become increasingly wary because they could easily come into contact with a foreigner or other person who the authorities believe has access to "secret information." Even bureaucrats have been frightened into limiting their contacts with the outside world as a precautionary measure.

All of this has only made the Russian state apparatus even more secretive and opaque. By a strange coincidence, the Duma passed the bill on treason during the second and third readings on Oct. 23, exactly 10 years after the Dubrovka theater siege in Moscow. Notably, during and after the hostage crisis, the Kremlin focused its wrath on journalists who dared to write unflattering reports about the intelligence agency's botched rescue operation that resulted in 130 deaths. Ever since, the authorities have become increasingly convinced that they have more to lose than to gain by allowing "enemy forces" such as the media and NGOs to monitor their activities.

With the new treason legislation, the Kremlin has now made it clear that it considers any attempt by civil society to question its monopoly on power as a threat to the state itself.

Andrei Soldatov is an intelligence analyst at Agentura.ru and co-author of "The New Nobility: The Restoration of Russia's Security State and the Enduring Legacy of the KGB."

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.