A Russian museum has put the work of an Uzbek photographer, currently under arrest in Tashkent and facing a trial for photos of her native land, on display in a sign of support for her and her work.

The exhibition of work from Umida Akhmedova’s 2007 book, “Men and Women from Dawn to Dusk,” went on display in Nizhny Novgorod’s State Museum of Photography late last month and will now travel to Rostov and Omsk before returning to Nizhny.

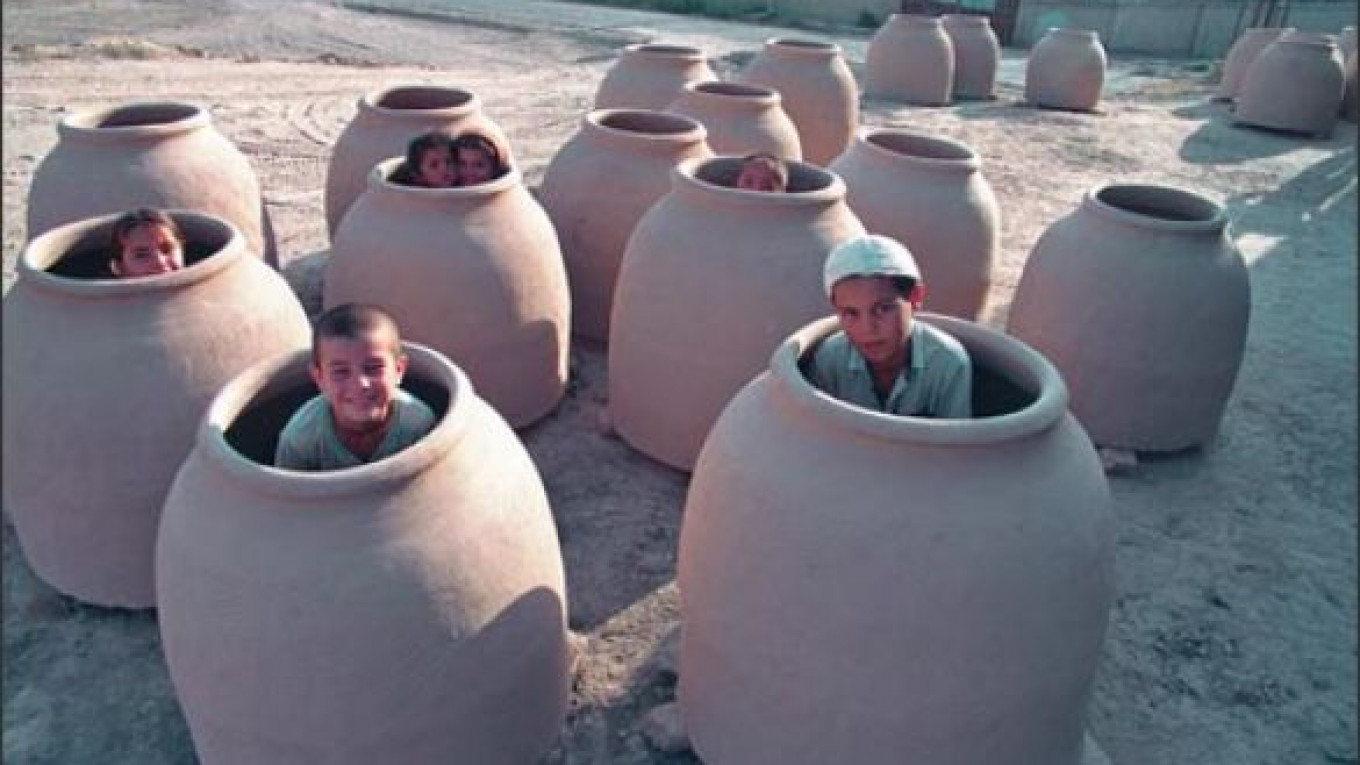

The images have brought accusations of defamation and damage to Uzbekistan’s national image from the Central Asian government.

Akhmedova’s work is “kind and beautiful,” said Vera Tarasova, director of the museum, who met Akhmedova last year and decided to put on the show as a way of showing Akhmedova’s innocence.

“People have the chance to get more closely acquainted with the photography from the album,” she said. “If a person never saw the work of Umida Akhmedova … but just read the information about the accusations, he might think that Umida Akhmedova really shows something terrible in her photographs. Coming to the exhibition, every person had a chance to … hold in their hands this album and understand the absurdity of the accusations.”

The 111 scenes mainly from rural Uzbekistan show the men, women and children of the country in a gentle manner.

“Never in my life did I think that my photographs, taken with such enormous love toward my people, could turn out to be defamatory against my people!” Akhmedova wrote in a letter to Tarasova last month.

The project, which was financed by the Swiss Embassy’s Gender Program in Tashkent, portrays traditions and everyday life in Uzbekistan with a focus on gender inequality.

First questioned about her work in Tashkent in November 2009, Akhmedova is currently awaiting trial and has been banned from leaving the country.

If convicted, she will face up to three years in prison or six months hard labor, news portal Ferghana.ru reported.

Also under investigation is her 2008 documentary film “The Burden of Virginity,” made with her husband, filmmaker Oleg Karpov, which focuses on the social repercussions of the Uzbek wedding custom in which brides have to prove their virginity before marriage.

Akhmedova, 54, has been a photographer for more than 20 years. She has worked for, among others, The Associated Press and has won several prizes for her photos. She has also made numerous documentary films.

The expert panel in charge of Akhmedova’s criminal investigation concluded that “a foreigner, not having seen Uzbekistan, after seeing the album, will come to the conclusion that this is a country where people live in the Middle Ages. The photographer purposefully puts emphasis on the difficulties of life. In particular, she tries to portray our women as victims.”

Museum staff, journalists and photographers in Nizhny Novgorod have signed a letter asking the Uzbek government to guarantee Akhmedova’s well-being and drop all forms of harassment against her and other human rights workers in Uzbekistan.

Human Rights Watch has called on Uzbek authorities to drop what they say are slanderous charges against Akhmedova and to allow her to carry on with her work. “The charges against Umida Akhmedova reveal the absurd lengths the government will go to silence independent expression. … The case sets a dangerous precedent and is a threat to all Uzbek artists,” Europe and Central Asia director Holly Cartner wrote in a statement published on the organization’s web site.

One visitor to the exhibit wrote in the guest book: “I saw the photography of Umida Akhmedova and was reminded of the years I lived in Tashkent. Her work brought back memories of my childhood. All her photographs are done with love, and what’s more, they portray an accurate image of the Uzbek people in all areas of life. In the photographs, I didn’t see anything that could start a criminal trial. Umida reminded me of my homeland. Her exhibition is done very professionally. Thank you for the joy again, at least I see my fellow Uzbeks.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.