Now that the global financial crisis has abated, this is a good time to take Russia’s pulse. We have just edited a book with 12 chapters written by Russians and Americans. The consensus from the authors was clear: Russia has weathered a perfect storm of oil price decrease, reversed capital flows and political isolation following the August 2008 war with Georgia. Russia’s short-term prospects appear neither dramatic nor problematic.

Yet Russia faces serious structural challenges in the long-run. The book’s authors unanimously concluded that the current system is no longer suitable for the challenges ahead and is facing a dead end. This includes the economy, politics, the rule of law, Gazprom, the Commonwealth of Independent States, foreign relations in general, foreign economic relations and the armed forces.

This discussion is reminiscent of the one in the 1970s about how the Soviet Union would transition from “extensive” growth based on the mobilization of resources to “intensive” growth based on increased efficiency and productivity. The big difference is while reform of the Soviet economic system was not possible, reform of the current state-capitalist system is. In some cases, such as in the military, reform has already started. But if Russia is to succeed in the long run, it urgently needs more comprehensive restructuring.

The good news is that Russia has substantial assets — natural resources and human capital — and huge potential for further change. These changes are not going to be easy, but if they happen the country will be able to capitalize on the true value of its assets.

One of the most profound structural problem facing Russia’s future development is the erosion of federalism, the inevitable result of consolidating so much authority in the Kremlin under the power vertical model. Other broad areas of structural concern are the rule of law, state regulation of enterprise and innovation. Disturbingly, corruption has gotten worse since 2000. One consequence is that big companies are given an unfair advantage over small firms. This hampers the development of small businesses, which are important drivers of innovation in the West, as well as in Bangalore and other global technology centers. Apart from the software industry, Russia’s high technology is concentrated in large state corporations.

Rampant corruption is arguably the largest factor obstructing the country’s ability to develop its infrastructure. Another of Russia’s great problems is demography. President Dmitry Medvedev captured the scope of the problem when he said: “Every year there are fewer and fewer Russians, alcoholism, smoking, traffic accidents, the lack of availability of many medical technologies, and environmental problems take millions of lives. And the emerging rise in births has not compensated for our declining population.”

Important reforms are taking place in the military, where Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov is pushing ahead despite strong resistance from the officer corps.

In foreign policy, Russia’s current dilemma is: modernize or marginalize. It makes little sense for Russia to oppose the West. Instead, it should aspire to emulate and join the West. Russia does not have the resources to pursue a separate course. Arguably, the most important issue is whether Russia finally will be able to accede to the World Trade Organization. The country has little to gain from the development of the Customs Union with Kazakhstan and Belarus, which would instead represent Russia’s marginalization.

The current strategic outlooks of Russia and the United States vary greatly. U.S. President Barack Obama has gone out of his way to reset U.S.-Russian relations. The key line in his big speech at Moscow’s New Economic School on July 7, 2009, was: “America wants a strong, peaceful, and prosperous Russia.” The U.S.-Russian relationship has improved considerably since its low point following the war with Georgia, but its potential remains unfulfilled.

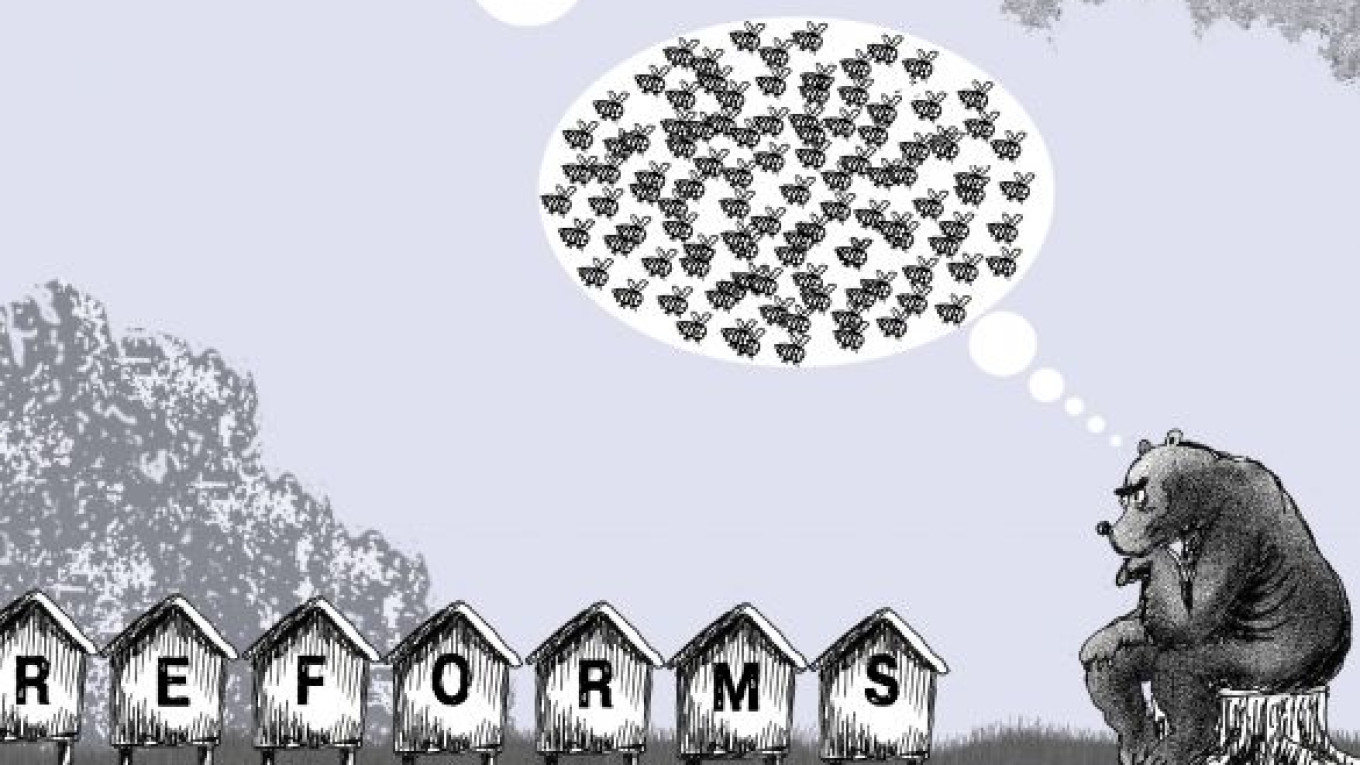

At present, the Russian leadership has a great opportunity. While it is evident that the current economic model cannot deliver sufficient growth in the next several years and the main problems are plain, the Kremlin does not face any apparent immediate internal or external threats. Therefore, the Russian government can launch reforms if it finds the political will and courage to do so.

But, of course, reforms always involve costs, not least to the insiders. The big question for the next couple of years is whether the stark analysis of Russia’s shortcomings, which have been largely overlooked by the country’s leaders, will prompt adequate reforms.

Anders Aslund and Andrew Kuchins, along with Sergei Guriev, are co-editors of the new book “Russia After the Global Economic Crisis.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.