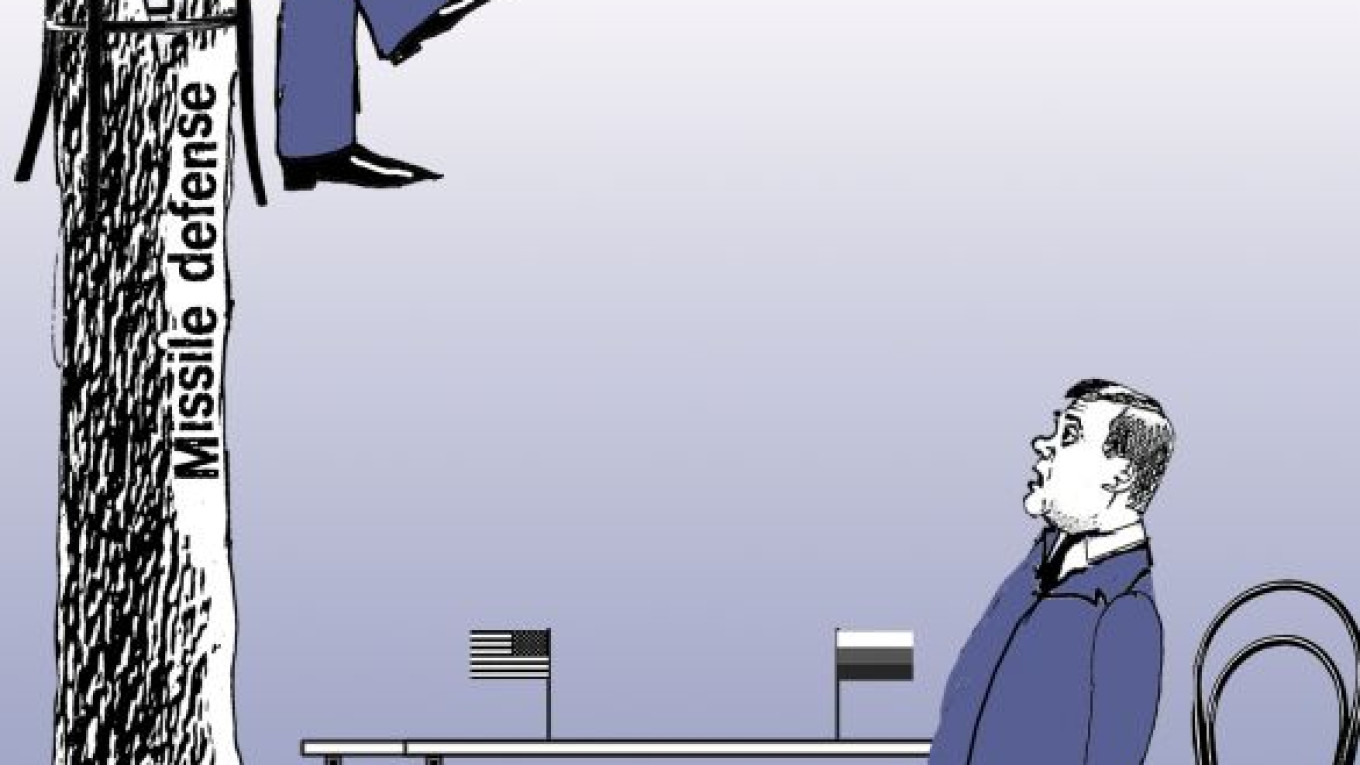

On Nov. 23, President Dmitry Medvedev — who, by the way, is still president — announced the measures with which Russia would respond if the United States deploys its missile defense system in Europe. Many commentators in the West and Russia agreed that there was nothing new in his threats to withdraw from the New START treaty with the United States and deploy Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad, saying his rhetoric was aimed primarily at Russian voters during a national election season.

That is largely true. Medvedev is clearly doing everything he can to avoid looking like a political lame duck or being eclipsed by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s vigorous election campaign. The “firm” and “patriotic” foreign policy stance is needed as a counterweight to the Kremlin’s vague economic agenda, the growing popular discontent over the ruling tandem’s return to power and the never-ending dominance of United Russia.

But that is only an initial and very superficial analysis. It would be a mistake to explain the Russian leadership’s most important strategic foreign policy and defense decisions purely on the basis of domestic policy considerations. In emphasizing those particular factors, observers tend to underestimate Russia’s real national security concerns. In fact, Russian history demonstrates that the foreign policy picture heavily influences the internal dynamics of this country. In fact, the Western forces’ cynical and colonialist foray into Libya, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s banal “wow” upon hearing of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi’s death, or the bloodthirsty comments made by U.S. Senator John McCain for the benefit of U.S. voters have done more to ensure Putin’s return to the Kremlin than could Central Elections Commission head Vladimir Churov.

It would be wrong to focus on the propagandistic aspect of Medvedev’s statements while ignoring the underlying message — namely that they denote the beginning of a crisis with the United States on nuclear arms and the overall strategic relationship between the two countries. This crisis has many dimensions, and the disagreement over missile defense is only its most striking manifestation.

The fundamental reason behind Washington’s activity in the field of missile defense is its desire to achieve complete security for the entire continental United States. That goal drives all of Washington’s national security policy and thinking.

However, today’s technology and economic situation make it impossible to create a missile defense system capable of guaranteeing protection against a massive nuclear attack. That is why the United States has chosen to work toward this goal in stages, first creating a “limited” missile defense system to stop missiles fired by “rogue states.” However, it is obvious that any “limited” missile defense system would be no more than an interim step toward building a full-scale missile defense system to provide guaranteed protection of U.S. territory against any nuclear missile attack. A lack of desire is not stopping the United States from creating and deploying a full-scale missile defense system now, but technological and economic constraints make it infeasible at present.

Thus, any “limited” versions of a U.S. missile defense system — provided it really is directed against missiles coming from Iran or North Korea — would essentially be “experimental trial runs” designed to perfect the technology needed for the later deployment of a full-scale missile defense system to protect the continental United States.

Of course, Washington’s missile defense goal is to achieve complete and unassailable national security. But as former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger aptly said, “Absolute security for one means no security for the rest.” And that is the concern underlying Russia’s position regarding any configuration of the U.S missile defense system.

At the same time, it is clear that Russia has no realistic way to stop or delay Washington’s plans to pursue its missile defense program. There is a strong consensus among U.S. lawmakers and the public on the need to achieve the greatest possible protection of the nation’s territory against any foreign missile attack, including possible strikes from Russia or China. For its part, Russia has nothing to offer in return for Washington’s belief that absolute invulnerability is attainable. Recall that when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev met with U.S. President Ronald Reagan in Reykjavik in 1986, he offered complete nuclear disarmament in return for a U.S. promise to abandon its Strategic Defense Initiative. That proposal was rejected. Washington’s missile defense program is closely linked to the idea of global hegemony that underlies all U.S. foreign and defense policy.

As a result, negotiating with the United States on missile defense is entirely futile — a conviction that negotiations in recent years have only reinforced in the minds of Russian leaders. Every attempt to draw the United States into an agreement on some form of restriction has proven completely fruitless. In effect, all interactions with the United States on this question have only confirmed the nature of Washington’s “long-term” missile defense policy — one that ultimately threatens the basis of nuclear deterrence and, consequently, the very foundation of Russia’s national security.

Under such circumstances, Russian leaders are faced with a choice: either continue making futile attempts to negotiate with Washington on missile defense or resort to a contingency plan. As experienced leaders with a realistic grasp of world affairs, Medvedev and Putin should have had a “Plan B” all along — and they did. It was that plan that Medvedev disclosed on Nov. 23. Of course, domestic policy considerations played some role, but the main significance of the speech was that Russia is officially putting Plan B into action. It would be very unwise for anyone to ignore that clear signal.

Not surprisingly, Medvedev said nothing new in those statements, and the measures he announced are already being implemented. Russia’s Plan B has been under development for a long time. Development and testing have long been conducted on new nuclear warheads and upgraded missiles to carry them. These include the Lainer, Avangard and Yars missiles — with the Yars already in production. A network of new long-range early warning radar stations is under construction, one of which is the station being built in Kaliningrad. Systems are also being developed for the “destruction of the information and control apparatus of missile defense systems.” In this regard, recall that the Sokol-Echelon program for destroying U.S. early warning satellites was renewed in 2010. Also under way is the scheduled replacement of Tochka-U missiles systems with the new Iskander-M missiles in Russian army brigades. And of course, those upgrades will eventually be applied to the 152nd missile brigade in Kaliningrad as well.

And now, thanks to the increase in Russian defense spending through 2020, many of those programs can be accelerated and moved toward serial production and deployment. With that in mind, Medvedev was able to put Plan B into action. Russia continues to focus on the military and technical means required for countering the U.S. missile defense system. At the same time, the resources needed for implementing Russia’s Plan B are realistic and relatively modest. What’s more, the gradual and rather slow way that the U.S. missile defense system is being developed makes it possible for Russia to implement the program Medvedev has announced.

Ruslan Pukhov is director of the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies and publisher of the journal Moscow Defense Brief.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.