What if Sabonis, a 220-centimeter Lithuanian and one of the most stunning talents in the history of the game, had left the Soviet Union for the NBA during his prime in the mid-1980s?

What if his once-powerful legs had not been ravaged by on-court injuries and freak off-court accidents?

And what if, even after his injuries, he had immediately taken his game to the United States as the Soviet Union was collapsing?

For basketball connoisseurs, the answer to these questions is as evident as it is depressing: He would have been one of the greatest centers in NBA history.

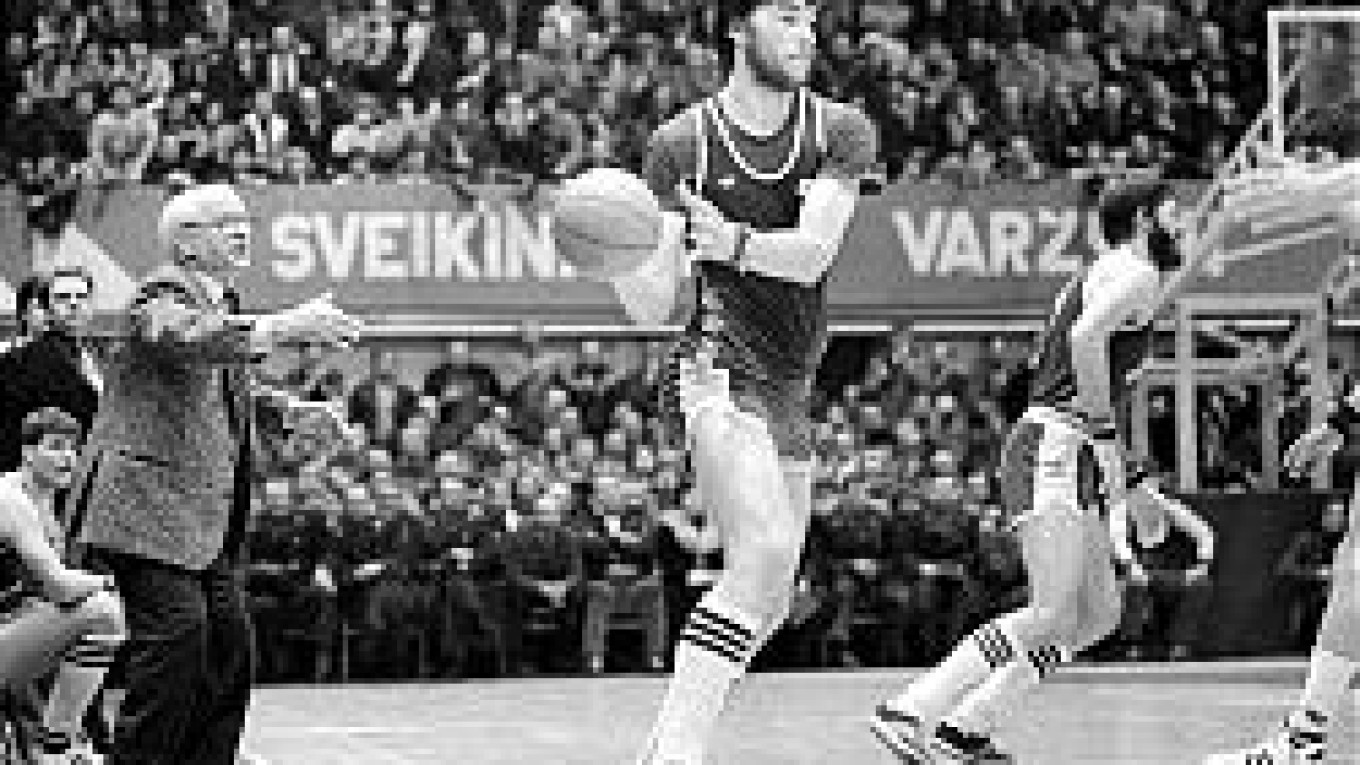

Sabonis, 39 on Friday, is in Moscow on Thursday to suit up for his hometown club, Zalgiris of Kaunas, Lithuania, against European powerhouse CSKA Moscow.

The occasion is a Euroleague match-up between the two clubs that were Soviet basketball's fiercest rivals in the 1980s. It is likely one of Sabonis' last playing appearances in Moscow, as he winds down his career at the club he started out with.

In Lithuania, where basketball is sacred, Sabonis is a god. In the rest of the European hoops world, he is only a step down from deification.

Glancing at his resume, it's not hard to see why. Except for an NBA championship, he has won practically everything there is to win in basketball.

He won three Soviet championships with Zalgiris, national and European club championships with Spanish club teams, two European Championship gold medals and one Olympic gold medal. He was named European Player of the Year six times in the 1980s and 1990s, and MVP of the 1985 European Championships.

But apart from championships and personal accolades, Sabonis is as renowned for a flair and versatility rarely seen in a player his size. He was a giant who played the game like a guard, grabbing rebounds and leading fastbreaks, eventually whipping a no-look pass to an unsuspecting teammate or stopping on a dime to drain a 3-pointer.

In a 1986 article on Sabonis in The Atlantic Monthly, American basketball guru Pete Newell described one of the most unbelievable plays he'd ever seen.

"A rebound bounced high off the rim and over toward the corner," Newell recounted. "Sabonis went up for it way out there, took the ball in one hand and -- still up in the air, off balance -- swept the ball backhand, like a discuss thrower in reverse, and hit a teammate in stride downcourt 86 feet away for an easy layup. I'd never seen a play like it."

Unfortunately, NBA fans never saw Sabonis at the top of his game showing his genius against America's best.

The Portland Trail Blazers selected the Lithuanian legend in the 1986 draft, but it was basically a throw-away pick, considering the Soviet authorities were not anxious to let a hero from one of their more restless republics seek fame and fortune in the West.

Furthermore, Sabonis' legs were proving fragile. He ruptured an Achilles tendon in 1987, and later aggravated the injury when he fell down the stairs racing to answer a phone call. His skill and ingenuity were it still intact, but he would never regain the spryness and spring of his youth.

Sabonis left the Soviet Union to play in Spain in 1989, eventually landing with Real Madrid in 1992. Having nothing left to win in Europe, he finally tried his luck in the NBA in 1995, joining the Trail Blazers. But by then he was a shadow of his former self.

Despite the injuries, a massive center with a deft understanding of the game is hard to come by, and Sabonis spent a stellar seven seasons with Portland, giving the team a presence in the middle and quickly becoming a fan favorite with his circus passes. He retired from the NBA last season, going home to Lithuania to play for Zalgiris.

Injuries and bad timing aside, just how good could Sabonis have been?

Mike Dunleavy, who coached Sabonis in Portland, said in 2001 that no center in the NBA at that time could have handled Sabonis in his prime, not even the game's most dominant player, the Lakers' Shaquille O'Neal.

Controversial college coaching great Bobby Knight was no less impressed when he saw the 17-year-old Sabonis play against his Indiana University squad during the Soviet national team's 1982 U.S. tour.

"I thought he was as good a prospect as I had ever seen," Knight said afterward. "He was stronger than Bill Walton. I couldn't get over what potential he had. Such a great raw talent."

But perhaps no one is more qualified to comment on Sabonis' potential than Alexander Gomelsky.

Gomelsky, the patriarch of Soviet and Russian basketball who coached CSKA against the center's Zalgiris teams, was at the helm of the Sabonis-led Soviet national team that won the gold medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, defeating a U.S. squad led by future hall-of-fame center David Robinson in the semifinals.

"He was the greatest European player of the last 100 years," Gomelsky told The Moscow Times this week. "He came to the NBA too late, obviously. But when you talk about players like Walton, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bill Russell, Sabonis was certainly on that level."

Only about 5,000 fans will get to see Sabonis live in Thursday's Zalgiris-CSKA match-up at the CSKA Universal Sports Complex. The game has been sold out for two weeks, with the army team marketing it as "CSKA vs. 224 centimeters of Sabonis."

Anyone else interested in seeing the aging legend play will have to watch the 9 p.m. broadcast on 7TV.

And even though Sabonis is far from being the player that once had NBA scouts drooling, the politically loaded history of the CSKA-Zalgiris rivalry offers an intriguing backdrop.

Kaunas, Lithuania's second-largest city and a town where sports fans watch Zalgiris games in dance clubs before the disco ball is lowered, became a key symbol for the growing Lithuanian nationalist movement of the late 20th century.

It was out front of the Kaunas Musical Theater in 1972 where a student named Romas Kalanta immolated himself to protest Soviet rule, sparking a student rebellion that was put down by Soviet troops.

But because Lithuanians had little hope of putting up any armed resistance to the Soviet Union, they turned to sports as a means of symbolically defeating the oppressors, said Arunas Pakula, manager for international operations at Zalgiris and a basketball journalist for the Vilnius newspaper Lietuvos Rytas.

"When our boxer Algirdas Socikas knocked out the Soviet great Nikolai Korolyov after World War II, there was a national celebration," Pakula said. "There were old women in the villages who didn't know anything about sports, but they knew who Algirdas Socikas was."

No team was a greater symbol of Lithuanian resistance that Zalgiris.

"CSKA was the Red Army team, and people identified the Red Army with all of the evils that came to Lithuania, " Pakula said. "So when CSKA came to Kaunas, everybody wanted to see Zalgiris beat them. There would be 100,000 ticket requests, and the gym only had 5,000 seats."

But even a zealous fan base isn't enough on its own to win championships, and from 1945 to 1984 the dominant Red Army team won 21 Soviet championships, including nine straight titles from 1976 to 1984. Zalgiris managed to win just one during that stretch, in 1951.

Zalgiris' fortunes began to change in the 1980s with the emergence of Sabonis, and at the height of the rivalry the Kaunas club defeated CSKA in the finals three seasons in a row from 1985-87.

In addition to the on-court battles and political symbolism, the Zalgiris-CSKA rivalry was marked by Lithuanian fears of behind-the-scenes intrigues in Moscow to rob the country of its top players.

The Lithuanians were deathly afraid that CSKA would pull out the trump card that allowed the team to fill its ranks with the Soviet Union's best young players: the draft.

As the official club of the Red Army, CSKA had the advantage of being able to draft young athletes for military service, though the players typically spent more time in sneakers and tank-tops than in fatigues and ***valenky***, traditional Russian winter boots.

In order to prevent Sabonis from being drafted and suiting up for CSKA, in the early 1980s he was matriculated into an agriculture institute in Kaunas. Though he rarely if ever attended classes, Pakula said there was one stipulation he had to adhere to.

"Once a month or so, he would have attend an evening faculty meeting at the institute and talk about basketball," Pakula said. "The room was always packed for those meetings. All of the professors wanted to hear him talk."

Other Lithuanian players were also enrolled in the institute for the same purpose, Pakula said, but the less talented ones actually had to attend classes.

Legend has it that as a backup plan to avoid being drafted, Lithuanian officials had prepared a document confirming that Sabonis had adopted two children from a local orphanage, thus giving him a military deferral as a father.

Despite CSKA's habit of stacking its roster with the top talent from every corner of the Soviet Union, Gomelsky said he never dreamt of trying to snatch Sabonis from his homeland.

"Of course we could have [drafted him], but I didn't want to do it," Gomelsky said. "The coaches in Lithuania knew that I wanted them to play excellent basketball up there.

"Plus, Sabonis would have never come to Moscow to play for CSKA," Gomelsky said. "Anybody who knows him knows that he could never play for the Red Army against his native country. He is so popular there, he could become president of the country if he ever wanted to."

Gomelsky's mention of Sabonis' political prospects isn't just a stray comment.

His status as a national hero has prompted media speculation that he could take up a political career in Lithuania once he hangs up his sneakers for good. But he has consistently downplayed any such suggestions.

"I still have a lot of work to do in basketball," Sabonis told Kommersant Sport this week. "There are already enough people ? looking for lucrative jobs [in politics] without me."

But according to Pakula, Sabonis has already been offered to assume one high-profile presidential duty.

Pakula said a Lithuanian state television station has decided not to ask President Rolandas Paksas to hold the annual address to his countrymen ahead of the New Year.

Paksas is facing impeachment over a scandal concerning his office's alleged connections with Russian organized crime.

According to Pakula, television representatives have asked Sabonis to give this year's speech instead, an offer that the player has declined.

"But he's been sick this past week," Pakula said. "So maybe he'll change his mind when he's feeling better."

Officials at state-run television stations LRT and LNK said they did not know of such an offer.

Basketball stars-cum-politicians are not without precedent in Lithuania. In October 2000, Gediminas Budnikas, who rose to fame as a Zalgiris and Soviet national team player in the 1960s and 1970s, was elected mayor of Kaunas, though he resigned three months later.

Pakula said he doubts that Sabonis will ever throw his 300 pounds into the political arena, but admits he would certainly find supporters among the electorate should he ever decide to run for office.

"Everybody would vote for him," he said.

Lithuanian basketball fans may yet have to add another, "What if?" to the list.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.