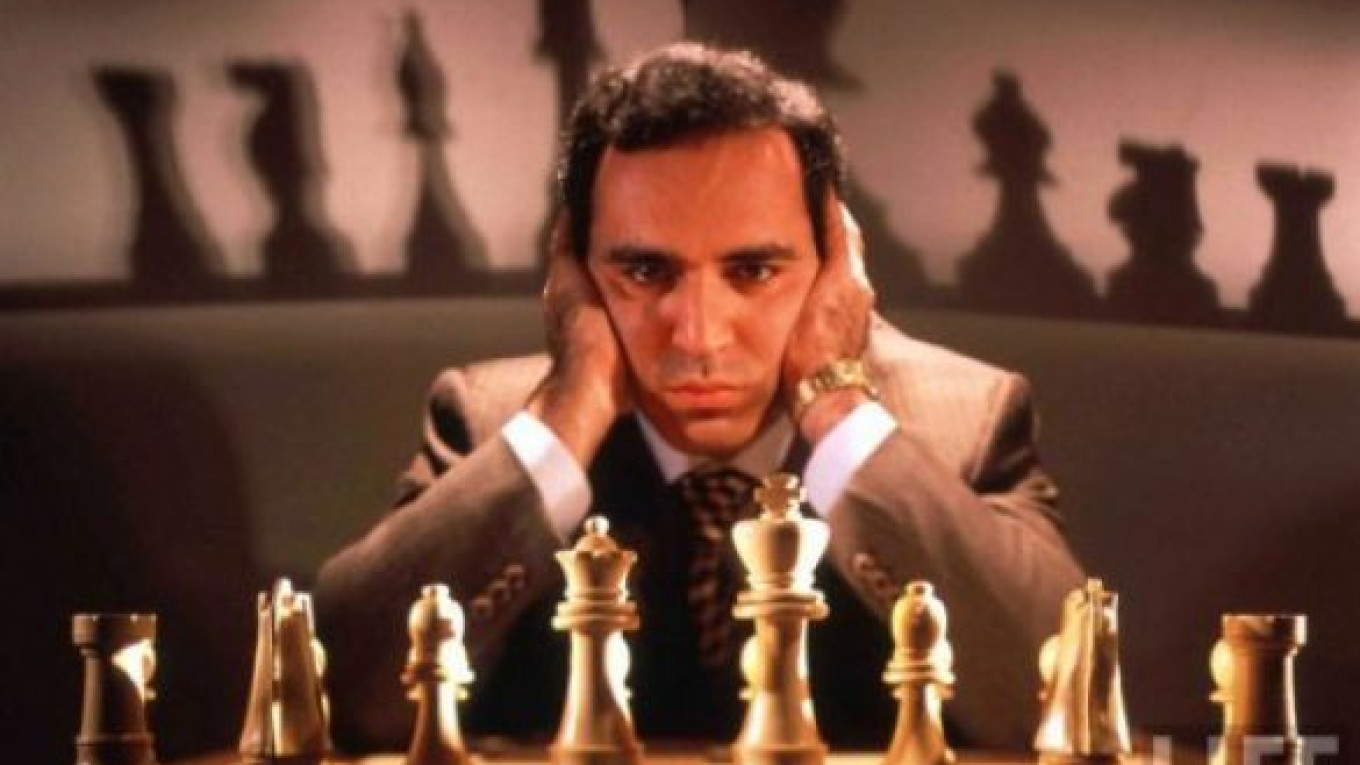

Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion-turned-political-opposition-stalwart, told a news conference in Geneva that he would not return to Russia for fear of criminal prosecution for his political activities, his website reported Wednesday.

Kasparov's announcement comes amid fears of a new wave of emigration of opposition-minded intellectuals, a fear intensified by the departure of liberal economist Sergei Guriev last week. Guriev's exit from Russia, which many believe was forced, was seen by experts as a major blow to civil society.

The news of Kasparov's plans to stay abroad is likely to intensify those fears.

Kasparov, 50, co-founded the opposition movements The Other Russia in 2006 and Solidarity in 2008, but he has kept a low profile for years, reportedly lobbying the interests of the Russian opposition abroad and providing financing.

He left Solidarity in April, citing his disagreement with the participation of the movement's members in elections, all of which he called "illegitimate."

Rumors about Kasparov's possible emigration were first floated on Twitter by Solidarity co-leader Ilya Yashin in April, in response to Kasparov's declaration that he'd quit as the movement's co-leader.

At that time, Kasparov said the rumors about his emigration were "greatly exaggerated" and that he was spending a lot of time abroad to persuade foreign governments to pass legislation similar to the U.S. Magnitsky Act, which imposed economic and travel restrictions on a number of Russian officials deemed by the U.S. to be implicated in human rights abuses at home.? ?

The chess legend says he began having “serious doubts” about returning after learning he might be involved in a criminal investigation.

But at Wednesday's news conference, Kasparov confirmed his intention to stay away from Russia.

"Right now, I have serious doubts that I would be able to travel out again if I returned to Moscow," Kasparov said, his official website reported.

"So, for the time being, I am refraining from returning to Russia," he said.

Kasparov had flown to Geneva to pick up the UN Watch Morris B. Abram Human Rights Award on Wednesday, which he was awarded for his "long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in Russia," according to a UN press release.

"I kept traveling back and forth until late February, when it became clear that I might be part of this ongoing investigation into the activities of political protesters," Kasparov told the news conference, referring to the criminal case opened into clashes between police and protesters at last year's anti-Kremlin rally.

Sergei Davidis, co-leader of Solidarity, which Kasparov left in April, told The Moscow Times that Kasparov had received two summons to the Investigative Committee to testify as a witness in the criminal case into the alleged mass riots that took place at that rally on Moscow's Bolotnaya Ploshchad.

"There are grounds to fear that Kasparov might be held responsible as an organizer, and if not, that his freedom to travel may be limited, which is very important for Kasparov due to his chess and political activities," Davidis said by telephone.

Kasparov was not listed among the official organizers of last year's May 6 opposition rally, nor was any other opposition leader, but he did march in front of a column of protesters, along with other opposition leaders.

One leader of last year's protest, Left Front head Sergei Udaltsov, is currently under house arrest awaiting trial on charges of plotting mass riots, which carry a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison. A dozen and a half of others have been prosecuted either on charges of plotting or taking part in the mass riots.

Anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny, who also helped lead last year's rally, is standing trial for the alleged large-scale theft of timber from state-owned KirovLes, a trial that many see as politically motivated.

Some of Kasparov's current and former political associates have accused him of cowardice and of letting the opposition movement down.

Vladimir Milov, a co-founder of Solidarity who quit the movement in 2009, accused Kasparov in April of getting "wildly frightened" of the possible limitation of his freedom of travel in connection with the Bolotnoye case, Milov wrote on his Livejournal blog at the time.

Milov said it was a "disgrace" that Kasparov repeatedly urged ordinary citizens to take part in unauthorized rallies while he himself had abstained from such rallies since 2007, when he spent his first five days in pretrial detention on administrative charges linked to participation in an opposition rally.

Yashin echoed a similar sentiment, writing on his blog on Ekho Moskvy's website in April that Kasparov "would have been very useful in Russia now when the bulldozer of repressions is running over innocent people."

"His intelligence and authority would have come in very handy here," Yashin wrote, noting that while Kasparov avoided unauthorized rallies since his 2007 arrest, Navalny and Udaltsov were "persistent" despite repeatedly ending up behind bars on administrative charges.

Others were more supportive of Kasparov's activities abroad.

Davidis, of Solidarity, said: "It is understandable that Kasparov, who can take advantage of his position while he is abroad and use his authority … prefers to be useful."

Denis Bilunov, a former senior member of Kasparov's movement United Civil Front and of Solidarity, said Kasparov would have "opportunities to take part in the political process" even if he is located abroad, particularly by communicating with associates over the Internet.

"Garry is watching everything that is happening in Russia very closely," Bilunov said by telephone.

In the past few years, Kasparov has spent a great deal of time teaching chess in the United States,? where he was reported by The New York Times to have bought an apartment in 2009.

But according to comments made in an article in April on Kasparov.ru, he has only Russian citizenship.

Contact the author at n.krainova@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.