It has been a punishing week for the ruble, and for many, the ghosts of previous crises feel all too near.

Despite the Central Bank pouring more than $1 billion a day into propping it up, the Russian currency fell 3 percent against the dollar — contributing to a 6 percent slide since the beginning of the year — and reached an all-time low against the euro.

Banks reported a surge in customers clamoring for hard currency, while commentators fretted about how far the slide could go. Battling to restore confidence, Economic Development Minister Alexei Ulyukayev on Tuesday backpedaled on plans to free float the ruble by 2015, and the Central Bank on Thursday pledged unlimited interventions to keep the ruble firm.

Russia was not alone, at least, as worries about slowing economic growth in China and anticipation — confirmed on Wednesday — of an easing of monetary stimulus in the U.S. diminished investor confidence in emerging markets worldwide.

But throughout the descent and despite reports of Russians hurrying to dump their rubles for euros and dollars, seasoned expatriates looked on with the knowledge that business, as always, will continue.

For American Bill Pigman, the volatility of his chosen home's currency first made itself known one fine day in 1994.

"I remember sitting at a restaurant and realizing that all this money that I have got, 35 percent of it, just went poof, disappeared," Pigman said.

Pigman, who now runs a fleet of school buses as well as importing and exporting construction equipment, has seen just about every face that business in Russia has to offer, including the innards of a jail cell in the early 2000s when his Russian partner stole their business from under him and orchestrated his and his wife's arrests.

The financial crisis of 1998 cost Pigman $500,000. A shipment of machinery he had sent to a gold mine under a letter of credit from Inkombank, then one of the largest commercial banks in Russia, went unpaid as the banking system crumbled and Inkombank vanished overnight.

But operating on the edges of a volatile currency has had its benefits as well — Pigman remembers the crisis of 2009 as his "best year" for exporting heavy equipment.

"No one knew what anything was worth, and they were right," he said.

Practices from those troubled times have already resurfaced, with certain sellers who used to accept payment in rubles now demanding dollars, he added.

Crises Remembered

While the image of a falling exchange rate provokes grim associations in Russia, the current decline has little in common with the perfect storm of late 2008 and 2009, when a host of external circumstances, among them the world economic crisis and plunging price of oil, pulled the currency down from 28 rubles to the dollar in December to 36 in February.

Nor can it be compared to the mass of internal issues that struck the country in 1998, said Daniel Wolfe, an American entrepreneur and finance executive with more than 20 years experience in Russia.

Nonetheless, memories of the steep inflation and government default that accompanied the ruble's descent remain in the population's financial thinking. "Part of the reason people get worried is that they conflate the exchange rate with other major problems," Wolfe said.

This anxiety has lingered also in the attitudes of some employees, who during previous devaluations have been known to ask that their salaries be pegged to a hard currency.

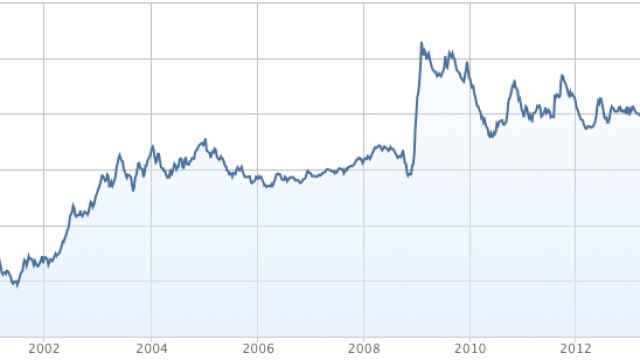

The ruble-dollar exchange rate from Jan. 1, 1998 to Jan. 30, 2014. The graph begins just after the ruble's redenomination. At the end of 1997, the rate was just under 6,000 rubles to the dollar.

The ruble-euro exchange rate from Jan. 1, 2000 to Jan. 30, 2014. The euro was launched in 1999.

But in his current position on the board of directors and management board of Kvadra, a utility company owned by billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov with 13,000 employees in the Moscow region, Wolfe does not anticipate this will be an issue.

"The reality is that the local economy is now largely de-dollarized, so I think there will be a lot less of that than five years ago and certainly much less than there was 10 years ago, when the economy was much more reliant on hard currency and hard currency imports," he said.

Austrian Owen Kemp, the former managing director of Hewlett Packard in Russia, can also recall times when employees asked for their salaries to be fixed in foreign currencies or simply requested pay raises when the ruble weakened.

"I understand why employees ask for this pegging. But of course they ask for it when the fluctuation is good for them and not when it is bad … so international corporations usually ignore them and sit it out," Kemp said.

From Kemp's perspective, the current decline is nothing to be too concerned about, even though, as a consultant for a number of high-tech companies, a rise in the price of imports could strike his clients' sales.

"Those that are more or less seasoned in their work in Russia don't tend to panic about something like this ... Over the decades, this has been a very stable, very promising market, and of course if you have so many advantages of growth and opportunity then you can accept the occasional bump in the road," he said.

Trust Elusive

The long-term view is easier for international corporations to adopt than it is for Russian individuals, who to this day are often unwilling to hold their savings in the Russian banking system.

This tendency to keep money in foreign currencies and offshore accounts is a worrying sign, and "not a recipe for the development of the economy," said American economist and Moscow resident Martin Gilman.

Now director of the Higher School of Economics' Center for Advanced Studies, Gilman's personal and professional connection with Russia stretches over two decades, including a period as the director of the International Monetary Fund's Moscow office.

Although he considers the present devaluation "very mild," Gilman recognizes that it awakens painful memories as well as reasonable concerns among Russians with foreign travel plans or assets and debts abroad.

In his estimation, a prolonged devaluation of the ruble, which some analysts have predicted, is by no means inevitable so long as the government and the Central Bank tighten monetary policy.

While recognizing the global factors that struck the currencies of Turkey and other emerging markets this week, Gilman also sees in the decline of the ruble an unintended consequence of Central Bank policies.

As part of preparations to set the ruble into free float and institute inflation targeting by the beginning of 2015, the regulator made certain adjustments — such as widening the corridor within which the Central Bank strives to maintain the exchange rate while still intervening to prop up the ruble — which suggested to investors that the ruble could be overvalued, Gilman said.

At the same time, when state revenue for 2013 was higher than anticipated, the government funneled the unexpected funds into the banking system while making additional liquidity available to commercial banks late in the year.

Unwilling to keep funds in an overvalued currency, the banks then poured the money into the foreign exchange market, buying up dollars and euros and, consequently, undermining the ruble exchange rate, Gilman said.

The same trend was seen in the banking system's responses to the crises of 1998 and 2008, he added, when the Central Bank responded by pumping money into financial institutions that immediately converted them into hard currency.

Provided there is no external crisis, "we could expect that a tightened monetary policy would firm up the ruble, and we may even find that where the ruble is now would be its nadir, really its lowest point," Gilman said.

Philosophical Outlook

Others, Wolfe among them, hold to another view — that the current devaluation is the ruble's natural descent to its market price, where it would have been if not for the Central Bank's management of the exchange rate.

"If you look at the economy and inflation over the last few years, there should have been about 5 percent devaluation of the ruble against the dollar anyway, and it has not happened. So it makes percent sense that if the government takes away its support we should expect a 15 or 20 percent decline in the ruble exchange rate vis-a-vis the dollar," Wolfe said.

While this will present problems for importers and for companies with foreign currency costs or debts, Wolfe said the decline will probably have a positive effect on the Russian economy in the long term, with demand abroad stimulating export and the increased price of imports encouraging local production.

If you live entirely within the ruble economy, there is little need to worry about the exchange rate — but for foreigners whose economic lives are spread among multiple currencies, there will be a price, and there is little that you can do to insulate yourself, Wolfe said.

"I have expenses in the U.S., so the devaluation does cause me some personal pain, but such is life. It is not the Russian government's job to worry about my U.S.-based costs," he said.

And so choosing to work in Russia remains, as it has been for many years, a matter of weighing the risks against the substantial opportunities.

Whether ultimately the ruble rises or falls, for Bill Pigman, with children to bus to school each morning and equipment to buy and sell, the ruble's instability is simply the price you pay for doing business in Russia.

Pigman operates in multiple currencies — he is paid in euros by schools, in dollars by private communities, and in rubles by individual families — and avoids long-term ruble-based contracts.

"We, the workers of the world, the businessmen of the world, what we know for sure is that we do not know where the exchange rate is going," Pigman said. "So you hedge, you hedge."

Correction: An earlier version of this story suggested that the ruble had fallen by 6 percent to the dollar in the week to Jan, 30. In fact, it fell by 3 percent over that week, and by 6 percent in the month to Jan. 30.?

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.