Compared to their U.S. counterparts -- such as commentator Anna Quindlen, who wrote of her desire to "drive a stake through Barbie's plastic heart," or Tom Forsythe, who photographed Barbie in a blender -- Goralik and the artists of "Barbiezone" take a more measured approach to Barbie. Their emotional distance is natural for people who first encountered the toy as adults.

Goralik described her first reaction to Barbie in an interview last weekend. It was in Israel in 1989, shortly after the Goraliks had emigrated from the Soviet Union, and 14-year-old Linor was buying a present for a little girl. "First I saw a Barbie in a green dress, then I saw that there was a Barbie for every taste," Goralik recalled. "I remember thinking that these people were geniuses."

Mattel's "marketing genius" is the central thesis of "Hollow Woman," as Goralik traces how the company has adjusted Barbie over the last five decades to follow developments in fashion, child-rearing, the women's movement and the sex makeup of the workforce. "Barbie's professions and Barbie's outfits are not innovations," Goralik said. "They aren't forcing anything on us from above."

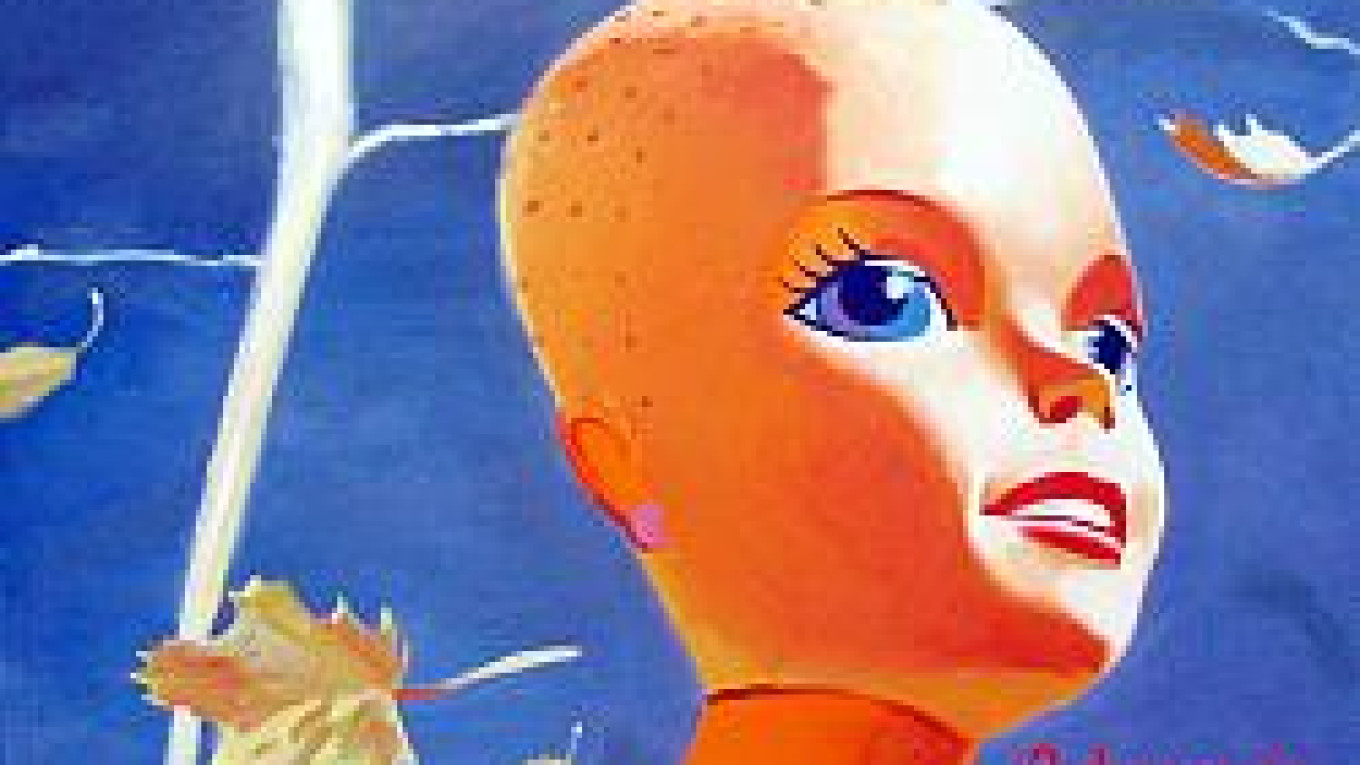

Barbie so eloquently summarizes mass culture that she makes an easy target for artists looking for a medium to express their criticism of consumerist values. The result is hundreds of sculptures and photographs of Barbie dolls contorted, chopped up and otherwise molested. Goralik dismissed this art. "You take something that's clean and make it dirty," she said. "Very funny."

Georgy Nikich, the curator of "Barbiezone" at RuArts, took a similar stance. "If you look up Barbie on the Internet, you'll come up with dozens of sites with pictures showing 'What I would do with Barbie,' all of them negative," Nikich said by telephone Monday. "The only positive site about Barbie is Mattel's."

Nikich said that the works at "Barbiezone" do not attack the doll, but "give her a new life." It might seem that Dmitry Tsvetkov's work is an exception. Tsvetkov, who has sewn cloth grenades and suits of money, contributed seven coffins for Barbie. But Nikich does not view Tsvetkov's work as criticism. "For a glamour girl like Barbie, seven coffins are like seven pairs of panties -- one for every day of the week," Nikich said. "Tsvetkov is simply giving her an accessory she doesn't have yet."

Other works address Barbie-related themes without referring to the toy directly. In "Fur Coat," a sculpture by Rostan Tavasiyev, a plush bunny sheds its gray pelt and dons a new pink one for the winter, unlike the other rabbits, who turn white to hide in the snow from predators. "Barbie is a superwoman, whose hypertrophied sexuality attracts attention," Tavasiyev said by telephone Tuesday. "And this bunny wants to be a superbunny -- he wants people to notice him, to like him."

Nikich suggested that the artists of "Barbiezone" had reacted to the toy in much the same way that Goralik did as a teenager. "To them, she is a very successful economic project," he said. "Russian artists don't see Barbie as an enemy."

The hostility toward Barbie expressed by Western artists and intellectuals could come from their adolescent perceptions of her as an unattainable ideal. "Barbie is like the queen bee of the high school," Goralik said. "She does all the right things, she's friendly, she helps people, she's beautiful, she's perfect."

So when the unpopular kids grow up, they use Barbie to act out their fantasies of violence against the prom queen. Goralik compared Mattel's lawsuits, like the one against the artist Forsythe for his distortions of the doll, to "the reaction of the most popular girl in school when she finds out everyone hates her."

Natives of the former Soviet Union, in contrast, are unlikely to associate Barbie with a real person. If they see Barbie as anything more than a hot product, it is as a remote fairy-tale creature, too ethereal to be disfigured. In the last chapter of "Hollow Woman," titled "Barbie in Russia," Goralik relates how a friend was reading an book about the United States in which a Soviet scholar slammed Barbie for extolling materialism, when she turned the page and saw a picture of the doll. "The photograph emitted the light of another world," Goralik quotes her friend as writing. "I lost my head from the realization that on other planets, in the universe where that girl was from, there's also life -- different, completely different, and perhaps better."

"Hollow Woman: The World of Barbie From Within and Without" (Polaya Zhenshchina. Mir Barbi Iznutri i Snaruzhi) is published by NLO. "Barbiezone" (Barbizona) runs through Dec. 20 at RuArts Gallery, located at 10 1st Zachatyevsky Pereulok. Metro Kropotkinskaya. Tel. 201-4475.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.