Feb. 1 marked what would have been the 80th birthday of Boris Yeltsin, the first president of the Russian Federation and the first popularly elected leader in the country's long history. In Yekaterinburg, President Dmitry Medvedev laid a wreath at a new monument dedicated to Yeltsin and called on the nation to be grateful for his service to his country. In Moscow at a concert to honor Yeltsin, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin cited Yeltsin's enormous role in giving the country a "second birth." For several days, Russia's mass media was filled with reports, discussions and programs dedicated to Yeltsin and his presidency.

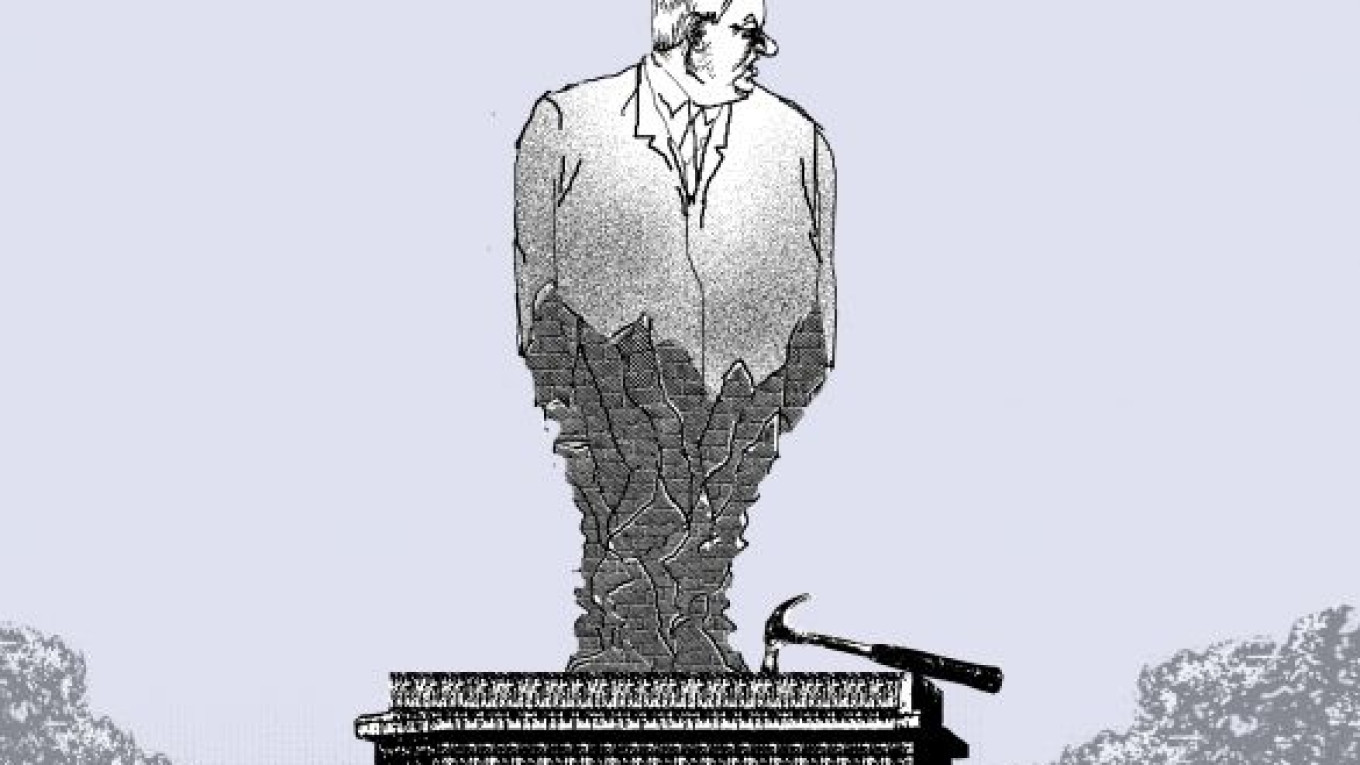

This did not, however, signal a substantive re-evaluation of Yeltsin, his presidency and the early period of Russia's statehood. Yeltsin remains a misunderstood and maligned figure in the country. More often than not, he is portrayed as a cartoon figure, and his long and multifaceted life in politics is usually reduced to a few acts, which are often misrepresented. But Yeltsin was a complex and contradictory man and leader, and his term as president was marked by several distinct phases.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s when I worked closely with him, he was energetic, forthright and clear-sighted, courageous in making hard decisions and taking full responsibility for them.

The greatest victories of his political career were in that period. When the Belavezha Accords were signed by the leaders of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine on Dec. 8, 1991, and then ratified by these countries' parliaments, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Its dissolution marked the end of the Cold War and the arms race, which had cost so much in material, spiritual and human resources and threatened the world with nuclear conflagration. The Soviet empire was dissolved peacefully from within, without civil war, battles over territory and property or mass-scale human dislocation. Liberated from the ideological yoke of Soviet totalitarianism, the nations that made up the Soviet Union were free to determine their own futures. Millions of former Soviet citizens began to enjoy rights and freedoms that were unthinkable during the Soviet era but were now codified in their constitutions.

Yeltsin and the first Russian government inherited a country that was bankrupt, in political ruins with billions of dollars of debt — and without any of the political, social or economic institutions of a modern state. Its citizens were exhausted by material deprivation and the politics of talk without action. As secretary of state during the first months of the new Russian government, I can attest that there were real risks of total economic collapse, famine and civil unrest. But a mere eight years later, when Yeltsin resigned from his post of president on Dec. 31, 1999, the Russian Federation had built the foundations of a functioning political system and economy, however imperfect.

These were the indisputable triumphs of Yeltsin's rule. Its tragedy lies in the fact that Yeltsin ?€” and we who served in his government ?€” failed to realize the potential of the Belavezha Accords to create a new democratic community of free nations. The power of the people was suppressed by the interests of bureaucrats who used the first stage of state and capitalist development to enrich themselves and strengthen or re-establish authoritarian rule. This occurred in part because Yeltsin categorically refused, no matter how often or how strongly we urged him, to establish a political party that would directly connect society and the leadership, especially on the question of essential economic reforms.

Yeltsin's refusal to form a political party was the understandable reaction of a former party boss who had observed and endured the malevolent supremacy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. But without a structure for constructive dialogue between the people and their rulers, the reforms were not a national effort. Instead, they were experienced as an extraordinary hardship.

This lack of real dialogue also opened a path for subjective decision making in the top echelons of power and later led to presidential rule in league with a group of oligarchs under Yeltsin and then siloviki under Putin and Medvedev. Constitutional presidential authority began to be used to curtail democratic freedoms and competitive market relations. Ultimately, the presidency turned into another version of Russian autocracy, complete with the anti-democratic appointment of successors.

There are millions of Russians who are bitterly disappointed in the course our country has taken. But there is no "end of history." It is never too late to return to values of freedom and democracy, to fulfill the promise of the peaceful transformations that were begun, but not finished, 20 years ago. To move forward and to modernize Russia, we first need to live through our past, to analyze and understand the lessons of our history and to honor those who dedicated their lives to ending the stranglehold of totalitarianism.

Last week at a conference dedicated to Yeltsin, I proposed that we dedicate a living symbol of freedom: a square with monuments to former human rights activist Andrei Sakharov, who helped us comprehend the value of freedom, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who legitimized that value and made it part of our language, and Yeltsin, who brought that value to life. Freedom Square would not be a museum of the past, but a place to gather, reflect, discuss and argue ?€” a place where we can commit anew to the values of freedom, democracy and dignity for all. That would be the best way to honor Boris Yeltsin.

Gennady Burbulis was secretary of state under Boris Yeltsin from 1991-92.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.