When the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum opens next week, a traditional fixture of the event will be conspicuously absent: renowned economist Sergei Guriev.

During the forum, Russian officials will undoubtedly repeat the usual lines about the country's untapped potential, its attractiveness as a gateway between Asia and Europe and its tremendous investment opportunities. But the other standard phrase used to pitch Russia at these forums — that the country has a "rich, educated human capital" — will sound particularly hollow amid Guriev's forced exit from Russia.

Guriev's forced exile is a disturbing wake-up call for all Russians who want a modern, democratic society.

Two weeks ago, Guriev announced from Paris, where his wife and two children live, that he would not return to Russia for fear of being named as a defendant in a possible third criminal case against former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky. "There is no guarantee that I won't lose my freedom [in Russia]," he told Ekho Moskvy on May 31. Guriev resigned as rector of the New Economic School, which he had turned into one of the country's top graduate programs in economics, and from the boards of Sberbank and four other companies.

Guriev's "crime" was co-authoring a 2011 report for then-President Dmitry Medvedev's human rights council in which he explained why the second criminal case against Khodorkovsky was unfounded, a conclusion that had been clear even to the most casual observer. In addition, Guriev donated 10,000 rubles ($320) last year to the anti-?corruption fund of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who is currently facing criminal charges in an embezzlement trial that many consider to be politically driven.

When an investigator from the Investigative Committee appeared in Guriev's office in April for a third round of questioning, the official unexpectedly pulled out a warrant to seize Guriev's computer hard drive and asked him if he had an alibi, presumably for a third Khodorkovsky trial.

After this, Guriev concluded that he had quickly gone from being a "witness" in the Khodorkovsky criminal case to effectively becoming a "defendant."

Shortly thereafter, he fled to Paris. Guriev feared that if he remained in Moscow much longer, investigators would pay another surprise visit, but this time with a new warrant to seize his passport and place him under house arrest.

Guriev's exit is a tremendous loss for Russia — at least for its progressive elements that want to pull the country in a new, modern direction. Guriev, an internationally recognized economist and former visiting professor at Princeton University, could have worked in any number of Western countries over the past 15 years, but he decided to stay in Russia and try to build a more modern, liberal and democratic Russia. In addition to developing the New Economic School, his other main modernization projects included participation in Open Government, Skolkovo and the president's human rights council.

As rector and professor at the New Economic School, Guriev's goal was to train young Russians to become innovative leaders, managers, economists and financial experts capable of modernizing Russia. And he was tremendously successful in this role, with roughly 80 percent of New Economic School graduates working in Russia in top-level positions at leading financial, consulting, real estate development and manufacturing companies.

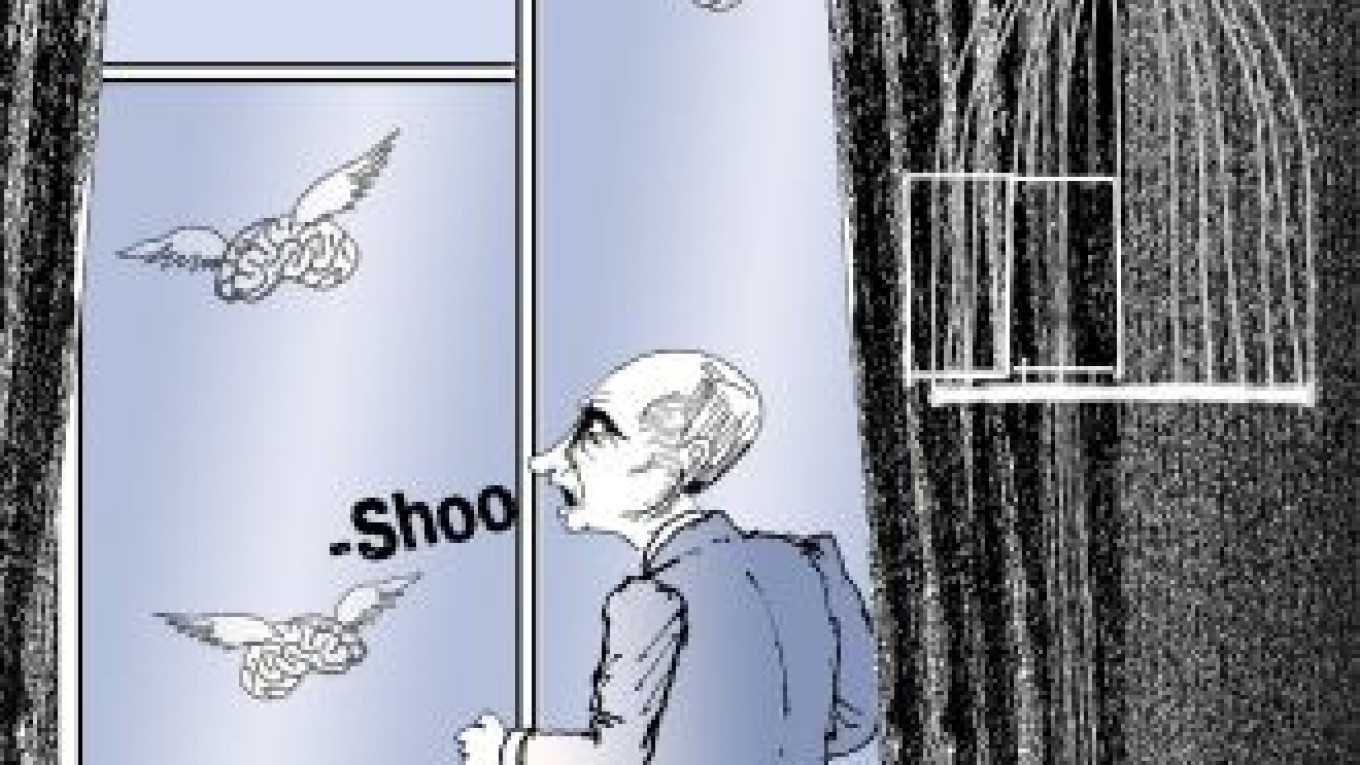

Yet Guriev's exile is a disturbing wake-up call for all Russians who want a modern, democratic society. Many will now question more than ever whether it makes sense to invest their future in a country that humiliates and persecutes its best, innovative talent.

So much for Medvedev's "Golden 100" list of top Russian talent, where Guriev, 41, had occupied a top position. And so much for the Kremlin's attempts to improve its image through "soft power."

The Kremlin's campaign against Guriev and others like him will only exacerbate the outflow of talent, and brain drains are always accompanied by capital drains. Yet it seems that the Kremlin has no real interest in stopping either of these drains.

"If he wants to leave, let him leave," President Vladimir Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov said on May 28, speaking of Guriev.

Notably, the Kremlin held the same disdain for Hermitage Capital head Bill Browder. The British businessman was once the Kremlin's favorite poster boy for selling Russia to global investors, but in 2006 the authorities declared him a "threat to national security" and denied him a visa after he started exposing corruption in Gazprom and other state companies.

The Kremlin's crackdown on members of its free-thinking, creative class is consistent with the Kremlin's strategy of controlling dissent and strengthening its power vertical. In a May 31 interview on Ekho Moskvy, opposition leader Boris Nemtsov said the Kremlin wants to rid itself of talented, independent-thinking Russians like Guriev. All the Kremlin and its army of bureaucrats need is enough qualified ?— and, most important, loyal — professionals to work in Gazprom, Rosneft and other natural resources companies, Nemtsov said, plus a few million to service them.

In other words, the Kremlin's dream is to create a Eurasian version of Saudi Arabia with its closed political institutions, state-sanctioned corruption and a largely servile, passive population that is content with living off government handouts.

The campaign against Guriev may also indicate an attempt by the Kremlin to exert more control over the field of economics. In an open letter published in late May, a group of 15 leading Russian economists wrote: "There has already been a period in our history when economic science and economic analysis was fully controlled by the state. It is well known how it turned out for the Soviet economy."

Guriev's downfall could mean the rise of people like retrograde, Kremlin-loyal economist Sergei ?Glazyev, who currently serves as Putin's economic adviser. It could also mean a return to the Soviet-style, distorted and ingratiating economic analysis in which Putin will be bombarded daily with good news about the country's inflated production figures and how great the economy is performing.

Above all, Kremlin's campaign against Guriev underscores the complete shallowness of its "modernization drive." True innovation, modernization and economic development is possible only when people are free — free to express their opinion, free to start their own creative projects and free from government abuse of power.

"I am a free person," Guriev told Slon in an interview in May 2012, explaining why he was not afraid of giving money to Navalny, Putin's bête noire. "As long as I don't break the law, nobody can prohibit me from speaking or doing what I want."

Or so he thought.

Guriev, like all normal Russians, shared Medvedev's banal belief that "freedom is better than no freedom." And that is precisely why he fled to Paris.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.