Today, his official title is detainee JJJBJC at the prison camp at the U.S. naval base on Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

He is one of eight Russian citizens identified by Russian investigators among the hundreds of detainees suspected of having links to the Taliban or al-Qaida. They were seized by U.S. troops in Afghanistan earlier this year.

Three of the eight, including Gumarov, come from Tatarstan, two from the republic of Kabardino-Balkaria in the North Caucasus, and one each from Muslim communities in Bashkortostan and the Chelyabinsk and Tyumen regions of western Siberia.

One had been an imam in his local mosque, another a wrestling champion, and a third a police lieutenant.

Most of them were seized while fighting against U.S. troops and the forces of the Northern Alliance near Kunduz in early 2002, according to Russian investigators.

At least half, and perhaps all, of the Russian detainees had arrived in Afghanistan before Sept. 11, 2001, at a time when the country was not thought of in the West as synonymous with Islamic terrorism. If it was thought of at all it was as a desolate territory where belligerent tribes were attempting to create a society based on a literal interpretation of the Koran.

Igor Tkachyov, the chief investigator of the North Caucasus branch of the Prosecutor General's Office and the head of a team of Russian investigators who visited the detainees at Guantanamo last month, said they told him they had gone to Afghanistan in search of a society where they could study Islam and feel at home.

"They are religious fanatics who underwent very serious brainwashing -- somebody found a crack in their psyche and made them believe they have to live under Sharia law," he said in a recent interview in the town of Yessentuki, in the southern Stavropol region.

Even though they could face harsh punishment in the United States, most of them do not wish to return to Russia, Tkachyov said. Russia has been pushing for their extradition.

Alexei Malashenko, an Islamic expert at the Moscow Carnegie Center, said each of the detainees may have had a different reason for going to Afghanistan, but the underlying attraction was likely the same.

"For Muslims, the idea that somewhere in the world there exists a place where life is fair and commanded by Islam is ineradicable," he said. "It could be that at a certain moment for this handful of people Afghanistan represented such a place and they took a risk in going there."

If they had stayed in Afghanistan longer, they may have become disillusioned, he added, just as they probably were with life in Russia after the demise of the Soviet Union.

For Gumarov, who after the collapse of the Soviet Union became a successful businessman trading in fertilizers, the desire to live under the laws of Islam grew so strong that in late 2000 he abandoned his wife and four children and two aged parents for Afghanistan.

"He told us he would go and see life there and, if he liked it, he would bring us all there," said his 70-year-old father, Shaifi Gumarov. "When I asked him what he would do abroad, Ravil said he was ready to tend sheep if he could live under the rule of Islam."

His mother, Sariya, who said their family was never religious, showed photographs of Ravil, a lanky man with dark hair. In most of them, he is happily embracing his fair-haired wife and children.

"We were common Soviet people, we never studied Islam or had any interest in religion, and I remember how my children made fun of my father, their grandfather, when he prayed, saying he was doing his exercises," she said.

Ravil, who never smoked or drank alcohol, started to pray and attend a mosque in 1997. He grew a beard, and his wife, Lilia, and two daughters began wearing headscarves when they went out.

His relatives said they could not explain the drastic change.

"He was not a man to be easily induced to do something," said his sister Rimma. "If there was any brainwashing in his case, a really sophisticated technique must have been used."

"We didn't understand what he was after. For us, he lived a wealthy life, had a good home and a car and could afford to help us out," said Sariya, a small, gray-haired woman who lives with her husband in a decrepit nine-story apartment building in Naberezhniye Chelny. "But he said that he wanted to live in a fair society, he didn't like life in Russia after perestroika and wanted to live according to Sharia and the rules of Islam."

Gumarov, like all but two of the Guantanamo detainees, went to Afghanistan via Tajikistan, according to Tkachyov.

"These men would go to Dushanbe, where they got in contact with members of the Islamic opposition to Tajik President Emomali Rakhmonov, who helped them get to Afghanistan," the investigator said.

Once there, the newcomers found themselves in a kind of totalitarian sect commanded by the Taliban, Tkachyov said. They were not allowed to be alone and had to do everything together, obeying strict regulations that left no time for anything else but prayers, he said.

The news of Ravil Gumarov being among the detainees in Cuba reached his relatives in March. None of them believed it until they received a postcard from him from Guantanamo in July, his mother said.

"In the first lines of the letter he wrote that he was safe and sound. The rest of the text was blackened by censorship," Sariya Gumarova said.

The last letter from him came in October. "I am fine. Sorry for leaving you in your old age without support. My journey has been prolonged by the will of Allah. Be Muslims, say your prayers. The Almighty has promised that we will meet," she read, her voice trembling and her eyes watery with tears behind her thick glasses.

Ravil Gumarov's wife sold their apartment and property in Naberezhniye Chelny and moved to her relatives' home in the regional capital, Kazan, fearing reprisals from authorities and neighbors.

"For many, Ravil is a stain on Tatarstan's image," his sister Rimma said.

Ravil Gumarov was an active member of a mosque called Tauba (Penance in Arabic), which is widely considered a stronghold of radical Islam in Tatarstan.

The white marble mosque with an angular star-shaped roof is the largest in eastern Tatarstan. It stands out from the prefab buildings that surround it in Naberezhniye Chelny, a city of 600,000 that sprang into existence in 1972 when Russia's major truck-producing factory, KamAZ, was founded on its outskirts.

An Imam

For MT Kudayev, at age 18, posing in his family's kitchen in the village of Khasanya. He left home three years later. | |

In the late 1980s, Naberezhniye Chelny earned nationwide notoriety for its violent youth gangs, and to save her teenage son, Airat, from the street, Amina Khasanova sent him to the newly opened madrassa called Yildyz, which means Star in Tatar.

Airat Vakhitov, now 27, entered the religious school in 1991 and five years later became imam of the Tauba mosque. At the end of 1999, after a troubled stint in Chechnya and with the Federal Security Service on his tail, he disappeared. Vakhitov turned up in Guantanamo with Gumarov and another compatriot from Chelny, Ravil Mingazov.

At the age of 6, her son had been hit by a car and suffered a brain injury, Khasanova said. Two years later he barely survived meningitis.

As a boy, Vakhitov suffered from terrible headaches and was unable to learn a single verse by heart in the Soviet school he attended, she said.

But after half a year at the madrassa, which was run by lecturers from Arab countries, he surpassed all other students in religious studies and was sent to continue his education at a madrassa in Turkey, she said. But he fled from there because the teachers beat students with sticks, according to his mother, a heavy women who was wearing a white headscarf.

Vakhitov crossed the border, was seized by Georgian border guards and put in a prison for juveniles. He spent several weeks there until his father went to bring him home.

Vakhitov returned to the Yildyz madrassa. "There were Arab teachers there and they gave him a very good knowledge of Islam," his mother said.

Foreign teachers of Islam flooded into Muslim regions of Russia in the early 1990s, often setting up their own madrassas and generously donating money for building new mosques and repairing old ones. The Islam they taught was radically different from the Islam that Russian Muslims had known from Soviet times.

Most of the foreigners were later expelled from Russia for preaching Wahhabism, an aggressive brand of Islam that calls for overthrowing secular authorities and establishing self-governing Muslim communities with laws based on the Koran.

The seeds sown by these missionaries sprouted in the North Caucasus. In 1998, the residents of several Dagestani villages drove out the Russian authorities and established the self-governed Muslim enclave of Karamakhi. It lasted for more than a year before Russian warplanes leveled the villages in September 1999.

But in Tatarstan, where state power has remained strong and is still concentrated in the hands of former Communist Party boss Mintimir Shaimiyev, such a rejection of secular authority was always out of the question. Those looking for an Islamic way of life had to look elsewhere.

Vakhitov went to Chechnya. After troops pulled out to end the 1994-96 war, Chechnya was de facto independent and became a haven for radical Muslims from all parts of the world.

They established institutions to equip students with the religious knowledge necessary for jihad and to train them in guerrilla warfare. The most notorious training camp in Chechnya was Institute Kavkaz, set up by Khattab, the Chechen warlord of Arabic origin who was killed earlier this year.

One Dagestani-based Islamic fundamentalist who visited one such camp in 1998 described its students as follows:

"These young men were real mujahedin, the warriors of Islam," he said in an interview last summer, on condition of anonymity. "In the camps they got what they missed in secular life: a common goal, a sense of community and the spirit of masculine camaraderie."

Several times before the second conflict began in 1999, Chechen emissaries from such training camps showed up at Tauba and recruited young men, luring them with prospects of better religious education from foreign preachers, one of the Tauba mosque's laymen said on condition of anonymity.

Under Suspicion

For MT Rasul Kudayev winning a wrestling match at age 8. Ten years later he was the Kabardino-Balkaria champion. | |

Vakhitov made several trips to Chechnya, the last one in early 1999.

That time, his mother said, one of his friends, Abu Bakar, told Chechens that the young imam was an FSB spy. According to investigators, Abu Bakar is an ethnic Udmurt named Alexei Ilyin who adopted Islam and attended Yildyz together with Vakhitov. Ilyin is reported to be on the national wanted list for fighting with Chechen rebels.

Chechens threw Vakhitov into a pit and he spent two months there, said Khasanova, his mother. "Chechens regularly beat Airat, damaging his kidneys, but he prayed and read the Koran the whole time and they could not kill him."

In April 1999, he was passed to a Tatar living in Grozny, who helped him return home. "The Chechens took away his documents, but Allah led my son safely through 14 passport checks on his way back," she said. Soldiers and police routinely accept bribes to let people without proper documents through checkpoints.

Vakhitov returned to his work at the mosque but he had changed, Tauba members said.

"He was an excellent public speaker, knew Arabic and could explain the Koran, but outside the mosque he turned into a very aggressive type who would attack people with his fists or even pull out a knife," one of them said. "Sometimes he would take a fancy skullcap from a worshiper and then not return it."

Another mosque layman said some of Vakhitov's sermons were anti-Semitic and he denounced the actions of the Russians in the North Caucasus as the second military conflict unfolded.

In October 1999, Tatarstan's Supreme Mufti Gusman Iskhakov asked Vakhitov to resign from the post of imam. A day after Vakhitov complied with the request, he was arrested by the FSB on charges of participating in illegal armed formations in Chechnya.

"My son was the best candidate for a show arrest at a time when Moscow was declaring a counter-terrorism operation," Khasanova said. "He talked too much, calling on Muslims not to trust the Kremlin's declared objectives in that war."

Suffering from inflammation of the lungs, Vakhitov was released 10 weeks later after investigators failed to come up with evidence against him. He was freed on a written promise not to leave the city until the investigation was over, his mother said.

At the end of the year, the FSB returned for him with an arrest warrant, but Vakhitov was not at home, Khasanova recalled. She notified his friends about the FSB visit, and he went on the run.

The Yildyz madrassa was shut down in September 2000 after some of its former students were implicated in terrorist attacks. Two of the 11 convicted in a December 1999 bomb attack on the Urengoi-Pomary-Uzhgorod gas pipeline, which traverses Tatarstan and supplies several European countries, had attended Yildyz. One of the suspects in the September 1999 apartment bombings in Moscow, Denis Saitakov, also was educated there.

Vakhitov went to Afghanistan via Dushanbe, his mother said. As he crossed the Afghan border together with a companion, they were seized by Taliban fighters who accused them of being Russian spies and locked up in a Kabul jail, she said.

When the U.S.-led military operation in Afghanistan started in the fall of 2001, Vakhitov was transferred to a jail in Kandahar. There he was found in December 2001 by a reporter for the French newspaper Le Monde, who was with the advancing U.S. troops.

"I spent seven months in Afghanistan, locked in a total darkness. Two nights a week we were beaten until dawn and they screamed, 'Confess, you brute, that you are the KGB agent,'" Vakhitov was quoted by Le Monde as saying. "They slit my friend Yakub's throat open in front of me, then hung me up by my hands and whipped me with electrical wire."

The Le Monde reporter allowed Vakhitov to call home on his satellite phone.

"'I am free, I am free,' he kept telling me," his mother said. "I asked him whether he had observed the fast during Ramadan in Afghanistan, he said no, and, knowing that it disappointed me, he told me he had learned the whole Koran by heart while in the Kandahar jail."

It is not clear how Vakhitov ended up in Guantanamo after being released from the Taliban jail.

The first letter from him reached Khasanova at the end of September. "Write me whether you are alive and healthy. I haven't heard from you for eight months and I am worried," he wrote.

"I put my hopes in Allah that my son will be back one day," Khasanova said. "And I pray he will not be tried in Russia. My son was looking for a refuge in Afghanistan and he cannot return to a Russian jail."

In Vakhitov's absence, the Yildyz madrassa was reopened under another name and only for female students.

The Tauba mosque now has two new imams, both educated in Saudi Arabia. Among its parish are men of Wahhabi appearance, who wear a beard but with the mustache shaved off. The mosque also is attended by women in standard urban attire -- such as fur hats and shorter skirts than required for strict observers -- and children in bright winter outfits, giving it a friendly, family atmosphere.

Vakhitov's mother said her son has a fiancee who will wait for him until he returns home.

A Wrestling Champion

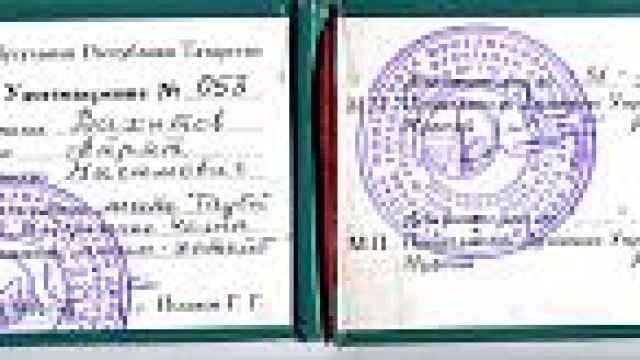

For MT Airat Vakhitov's identification card, issued by Tatarstan's Muslim Religious Board and signed by the mufti. | |

Another Guantanamo detainee, Rasul Kudayev, is not so fortunate. His fiancee married another man while he was in Afghanistan.

Kudayev, 24, is a native of Kabardino-Balkaria and in 1996 he won the republic's wrestling championship.

He was raised by his mother in the Balkar village of Khasanya, near the capital, Nalchik. The family's one-room house of crumbling brick now faces the skeleton of what would be the largest mosque in Kabardino-Balkaria. The construction has been dragging on now for 13 years.

His mother, Fatima Tekayeva, a nurse, said she brought him to Islam 10 years ago but he was never a devout Muslim.

"Rasul attended wrestling practice with much greater zeal and regularity than he attended the mosque or prayed," Tekayeva said reproachfully. She was wearing a white headscarf and a woolen dress that covered all of her body except her hands.

She divorced Kudayev's father when the boy was 10 and raised him and his elder half-brother on her own. Even by local standards, the family lives in poverty. The house's only room has a wooden floor, but the floor in the corridor and in the kitchen, where the family's life goes on, is cold concrete. There are hardly two mugs or forks that match.

Their home, however, is constantly full of young people who come to pay their respects to Tekayeva, known in the neighborhood for her piety.

"The police call me a spreader of Wahhabism among the young. But look at these Wahhabis," she said, pointing to her visitors -- young men, some chain-smoking and clean-shaven, sitting around a clumsy homemade table and chatting with her elder son, Arsen Mokayev.

They said Kudayev was a talented athlete and a regular teenager. Like his brother, he smoked, despite Islam's prohibition, and never showed any fervor in his religious duties. Judging by family photographs, he had never grown a beard.

A young ethnic Balkar man like Kudayev has little opportunity in his native republic. Balkars comprise only 10 percent of the population in Kabardino-Balkaria, which is governed mainly by Kabardins. Like the Chechens, the Balkars were deported to Central Asia by Josef Stalin in the 1940s, and after they returned to the North Caucasus, they never regained sufficient political power to match the Kabardins.

After completing the sixth grade, Kudayev stopped going to school so he could help his mother at home. Even without attending classes, he passed the school examinations, but he was not accepted at police school because the family could not collect the money for the necessary bribe, his brother said.

Kudayev earned some money by doing odd jobs, but he spent most of his time at home, going out mainly for wrestling practice.

In late 1999, he told his family he was going to Central Asia to further his career in sports. His coach, whose family had been deported to Kyrgyzstan, had told him there were good prospects for athletes in the region, his brother said.

Kudayev called his mother half a year later, just to tell her that he was fine. "When I asked him where he was calling from, he hung up," Tekayeva said.

She learned in April that her son was in Guantanamo. "I was watching a television report from Cuba and suddenly saw an inmate in an orange robe who walked exactly like my son, with his hands deep in his pockets," she said. "Then when Russian investigators began showing photos of Russian detainees in front of the camera, I recognized Rasul in one of them."

Tekayeva, who has not received any letters from her son, has resigned herself to his situation.

"It was Allah's will that my son was sent there, and it will be his will if he is brought out," she repeated several times. "I also don't expect any mercy for him from any government, neither American nor Russian. Let everything happen according to the wishes of Allah."

Tkachyov, the investigator, said Kudayev was the friendliest of the Russian detainees. When he visited him in Guantanamo, the first thing Kudayev did was ask him for a cigarette.

Tkachyov offered another version of how Kudayev popped up in Afghanistan. "He wanted to escape service in the Russian army. Kudayev fled to Georgia and then via Azerbaijan and Iran went to Afghanistan," he said.

Some of the other detainees also were of conscript age and had gone to Afghanistan to avoid the draft, he said. "Some told me they did not want to serve in the Russian army but were ready to take up arms to fight against Russia," Tkachyov said.

A Police Officer

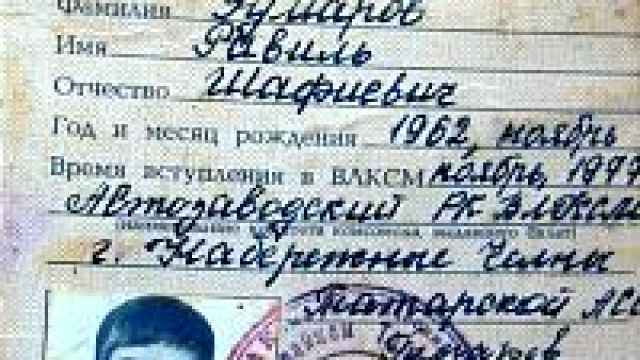

For MT Ravil Gumarov's 1977 Komsomol membership card | |

Shamil Khazhiyev, 31, expressed the strongest anti-Russian sentiments of all the detainees, Tkachyov said. During the first round of questioning in March, he provided investigators with a made-up name and personal details.

In reality he was a police lieutenant from Uchaly, a town of 40,000 in Bashkortostan.

In 1999, he was studying law at Ufa State University by correspondence, and upon finishing the course he expected a career promotion, his colleagues said.

"We don't know what happened to him or how to explain his escape to Afghanistan," said Yamil Mustafin, the acting head of the town's police force.

Leonid Syukiainen, an Islamic expert from the Institute of State and Law of the Russian Academy of Sciences, compared the Afghanistan fugitives to the idealistic Westerners who moved to the Soviet Union after the 1917 Revolution to help build a socialist society

"Of course, there had to be a combination of reasons for these people to flee to Afghanistan, but I believe their strongest motive was that they sincerely sought a fair Islamic society there," he said.

Investigators disclosed the names of other Russian detainees in Cuba, but refused to provide any other information about them. They are: Ruslan Odigov from Nalchik, Kabardino-Balkaria; Rustam Akhmerov from the Chelyabinsk region and Timur Ishmuradov from the Tyumen region.

The United States has not charged any of the detainees, but if charged with being members of a terrorist organization that plotted against U.S. citizens, they could face capital punishment, Tkachyov said.

A U.S. military order covering the trial of noncitizens in the war on terrorism, signed by President George W. Bush, says individuals "may be punished in accordance with the penalties provided under applicable law, including life imprisonment and death."

But according to Tkachyov, the Russian detainees have proven useful to U.S. investigators trying to get a fuller picture of the activities of al-Qaida and the Taliban.

"The Russian inmates were rather helpful in this, although they were not members of the Taliban but fought under the banner of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a radical Muslim organization that united natives of former Soviet republics in Afghanistan," he said.

Russian authorities have said they intend to ask the U.S. government to extradite the Russian citizens.

"We will insist on their extradition, but there would be certain obstacles," Deputy Prosecutor General Sergei Fridinsky told Interfax earlier this month.

To win the detainees' extradition, Russia must have evidence against them, but U.S. authorities have provided no evidence so far that they were carrying arms when detained or had committed any other crime in Afghanistan, Fridinsky said.

Tkachyov said prosecutors in Russia would like to be able to try them on charges of participating in a criminal organization, being mercenaries and illegally crossing Russia's borders.

U.S. Ambassador to Russia Alexander Vershbow told Interfax in late November that if the detainees were to be held responsible under Russian law, they would be handed over to Russian authorities.

Tkachyov, however, was not optimistic that they would be handed over to Russia any time soon. He said the detainees planned to seek political refuge in the United States or another country. "They believe everybody needs them," he said.

Mokayev, the brother of detainee Kudayev, said it was no mystery why the detainees preferred to risk harsh punishment in the United States rather than return to Russia, where they would face a relatively short prison term.

"If they get into the hands of Russian investigators, they will be tortured and humiliated, and their will and inner beliefs might be broken," said Mokayev, who served two years in prison in the early 1990s for a petty criminal offense. "In the States, even if they are executed, they will think they are dying for their religion, and for a devout Muslim this is just fine."

Deputy Justice Minister Yury Kalinin on Tuesday promised to guarantee their rights if they are handed over to Russian authorities.

"We give a full guarantee that all individuals handed over to us for investigation or for criminal punishment after a verdict is rendered won't face any kind of violations," he said at a government human rights conference in Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.