Soon after the protests in December, President Dmitry Medvedev introduced a series of bills to the State Duma designed to liberalize elections. Foremost among them was the proposal to reinstate the direct election of governors, which then-President Vladimir Putin cancelled in 2004 after the Beslan school attack that resulted in 334 hostage deaths.

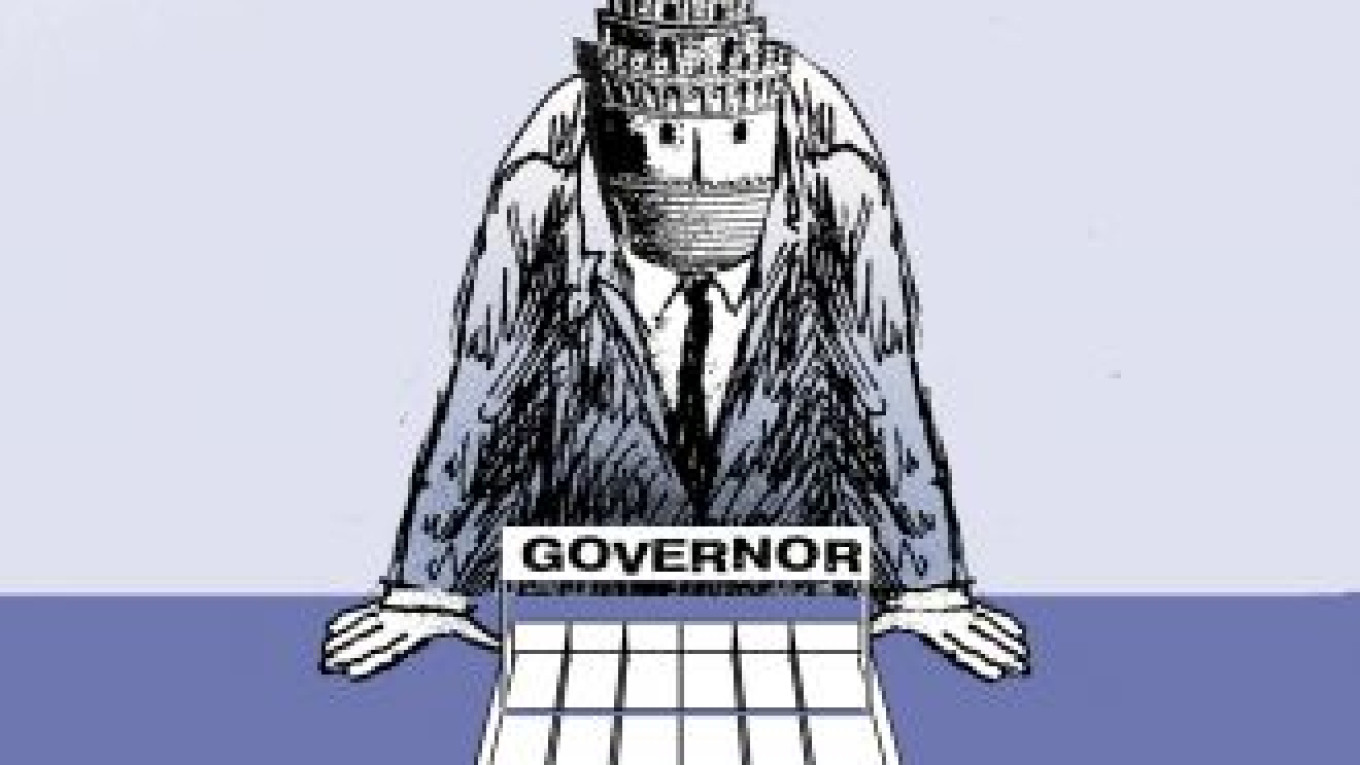

The authorities would like us to believe that the new law will help improve elective government in the regions. But the Kremlin would still have plenty of ways to influence and control the governors elected by the people. The federal authorities know exactly how to remove unwanted candidates from a race, regardless of the number of signatures they have gathered.

They also have ways of removing a candidate even after he has registered, such as disqualifying him for an alleged violation of electoral rules. One of the tried-and true tricks used by the authorities is to cite minor discrepancies among citizens' signatures required for a candidate's registration, such as singling out people who signed in a particular region but did not have a residency permit to live there.

The one phrase of the bill that has evoked the most controversy concerns the implied suggestion that the gubernatorial candidate's party "consult with the president." Of course, that is not the firm Kremlin "filter" that Prime Minister Vladimir Putin originally promised in December when he first mentioned the idea of returning gubernatorial elections, but it does suggest that the federal authorities will have a way to control the process through administrative channels and resources.

To be exact, the bill states that parties "may consult" with the president about their candidate. But everyone familiar with Kremlin politics knows that candidates and their party leaders have almost always "consulted" with the Kremlin and its representatives. The Kremlin continues to hold numerous informal methods to wield authority over the parties, and this will surely continue under the new legislation.

Funding for almost all of the regions is highly dependent on Moscow's goodwill, so the regional political elite are very compliant with their leaders' wishes. In the 1990s, when Russia's miniscule national budget equaled that of a medium-sized state in the United States, regional leaders could permit themselves certain liberties and turn their back to Moscow. But now, when the federal budget allocates billions of rubles for earmarked programs and subsidies, arguing with Moscow is not an option. In fact, 70 percent of the funding for regional budgets comes from Moscow.

Nonetheless, voters still might lessen, or even overcome, the Kremlin's influence over governors. It is a well-known fact that when voters become active on a large enough scale, they can override many schemes or manipulations that leaders have devised, including those dreamed up by the Kremlin.

If voters mobilize themselves around direct gubernatorial elections, they could use this as a starting point for making the entire political system more accountable to civil society. This could be the first real liberal political institutional reform under Putin's rule.

But if voters don't take advantage of this opportunity, they risk being duped once again by Kremlin-friendly populist regional leaders who present themselves as "benevolent boyars" and who try to buy the people's loyalty with cheap handouts and empty promises of a bright, happy future.

Georgy Bovt is a co-founder of the Right Cause party.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.