As winter approaches, many people in Central and Eastern Europe remember the chill caused last winter by Russia’s deliberate cutoff of gas supplies. That shutdown was a harsh reminder that gas is now the Kremlin’s primary political instrument as it seeks to re-establish its privileged sphere of interest in what it thinks of as Russia’s “near-abroad.” If Russia is allowed to continue imposing Moscow’s rules on Europe’s energy supplies, the result will be costly — not only for Europe, but for Russia as well.

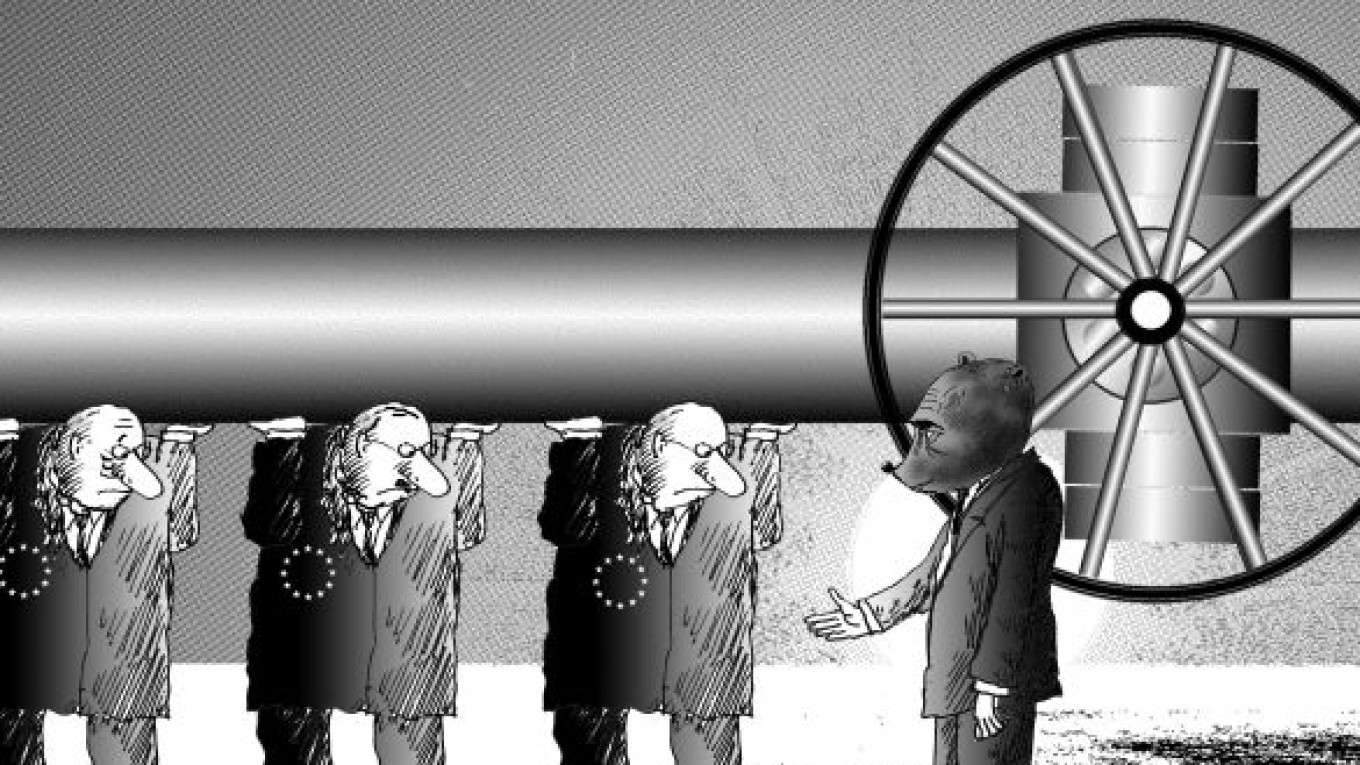

So it is past time that the European Union stop treating energy as a bilateral issue, with some of the larger member states trying to protect their own narrow interests at the expense of the common European good. The EU urgently needs to build a common energy policy and a single market for natural gas. Until both are established, there is a grave risk that Russia will use new blockades to continue the kind of divide-and-rule policy that the world has witnessed since Vladimir Putin came to power.

The planned Nord Stream gas pipeline on the bottom of the Baltic Sea is a good example of the problems that everyone in Europe is facing. The pipeline has been established as a Russian-German-Dutch consortium, but it is Gazprom that is in the driver’s seat with 51 percent of the shares. Nord Stream will enable Russia to deliver natural gas directly to Germany without using the existing land-based connections.

At first glance, there seems to be no problem. But the real reason that Russia wants to build Nord Stream, which is more expensive than the existing gas pipeline network, is that it will enable Russia to interrupt gas supplies to EU member countries like Poland, the Baltic states and Ukraine, while keeping its German and other West European customers snug and warm.

Countries that have good reason to fear a Russian manufactured chill have loudly proclaimed that Nord Stream is politically rather than economically motivated. After all, it would be much cheaper to expand existing land pipelines than to build new ones under the sea. Moreover, Russia’s ability to meet future gas demand from commercially viable reserves suggests that Nord Stream could be used to cut off gas sales to unfavored clients.

Yet these concerns have been pushed aside by the powerful pro-Nord Stream lobby, led by former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who, having approved Nord Stream while in office, was quickly hired by Gazprom after he left it. In most democracies, such a move would have quickly received prosecutorial attention. But no serious investigation of the propriety of Schröder’s dealings was ever initiated, perhaps because of the scale and importance of German-Russian economic ties.

In November, Nord Stream was given a surprising go-ahead by three Scandinavian countries that will lend their seabed to the project: Denmark, Sweden and Finland. They seem to regard the case as a “technical issue” and are now satisfied because environmental guarantees have been given.

But Nord Stream is no “technical issue.” The concerns of countries that fear being left out in the cold must be addressed, which is why it is necessary to establish a single EU market for natural gas. That way, no one would be left exposed to Russian pressure.

Europe undoubtedly needs Russian gas, but fears that this gives the Kremlin a monopolistic stranglehold over Europe are exaggerated. Russia’s share of total EU gas imports is just above 40 percent today, compared with 80 percent in 1980. Moreover, Russian gas represents only 6 percent to 7 percent of the EU’s total primary energy supply.

So, in general, dependence on Russian gas should not be feared. The problem is that some countries in the eastern part of the EU are much more dependent on Russian gas than the average figures suggest. Thus, they must be guaranteed the kind of solidarity that is fundamental to EU membership.

Last year’s experience with interrupted gas supplies did have one benefit: a new push for alternative routes, like the Nabucco pipeline that is intended to bring Azeri gas to Europe through Turkey. An early warning system on potential supply cuts has also been agreed between Russia and the EU. And it looks like Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko has charmed Putin into concluding a new gas deal. Yet anxiety remains high in the countries most exposed to new supply cuts.

It is in Moscow’s own interest that the EU deal with it as a united entity. Continued fear and uncertainty about Russian gas supplies would undoubtedly lead the most-exposed EU countries to seek to protect themselves by blocking EU-Russian negotiations on new partnership and cooperation agreements.

In his state-of-the-nation speech in November, President Dmitry Medvedev stressed the need to modernize the Russian economy. Closer cooperation with the EU is the most obvious way to make this possible. But, so long as Russia is perceived as an energy blackmailer and not a partner, such cooperation will be impossible.

Uffe Ellemann-Jensen is a former foreign minister of Denmark. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.