There is Adolf Hitler's cap, shoes and documents that describe in painstaking detail how SMERSH officers discovered the Fuhrer's body, identified it and eventually destroyed it. There is information about 60 schools set up by German military intelligence, the Abwehr, to train Soviet defectors and POWs as saboteurs and spies before parachuting them in behind front lines.

And although Ian Fleming twisted history by depicting horrible SMERSH spies in his novels set in the 1950s, when the agency was no longer called that and performed other functions, the exhibit displays genuine gadgets that would appeal to James Bond fans: micro-cameras, a pen that shoots, a notebook that dissolves in water and tools used to open diplomatic envelopes undetected.

Yet the exhibit, which appears to be part of a Federal Security Service public relations campaign to romanticize its history, is equally remarkable for what it does not show or tell.

Not a single item at the exhibit mentions the zagradotryady, special forces deployed in the army's rear to shoot at those who retreated against orders, or SMERSH's role in the filtration of liberated Soviet POWs.

"They [military counterintelligence] are distancing themselves from what was before and after the war and showing the most glorious period of their history -- when they were fighting the Nazis," said Sergei Kozhin, a senior research fellow at the Central Museum of the Armed Forces, where the largely FSB-organized exhibit takes up one hall. "The idea is clear -- they want to show their contribution to the victory. It is not a monograph, where all aspects have to be shown. It deals mainly with the heroism."

Commemorating SMERSH heroes -- more than 6,000 of them died at the front -- and denying the darker side of the agency's work appears to be the FSB's design.

"Military counterintelligence was not involved in punitive operations and did not carry out repressions at the front," Lieutenant General Alexander Bezverkhny, head of the FSB's military counterintelligence directorate, was quoted as saying in a long interview with Krasnaya Zvezda newspaper last month.

"SMERSH is our living legend," he said.

Although the Cheka's osobiye otdely, or special departments, in the Red Army were created back in 1918 and operated throughout the army's modern history, on April 19, 1943, Stalin signed an order subordinating military counterintelligence to the People's Commissariat of Defense.

Since Stalin headed the commissariat, the head of military counterintelligence, Viktor Abakumov, reported directly to him.

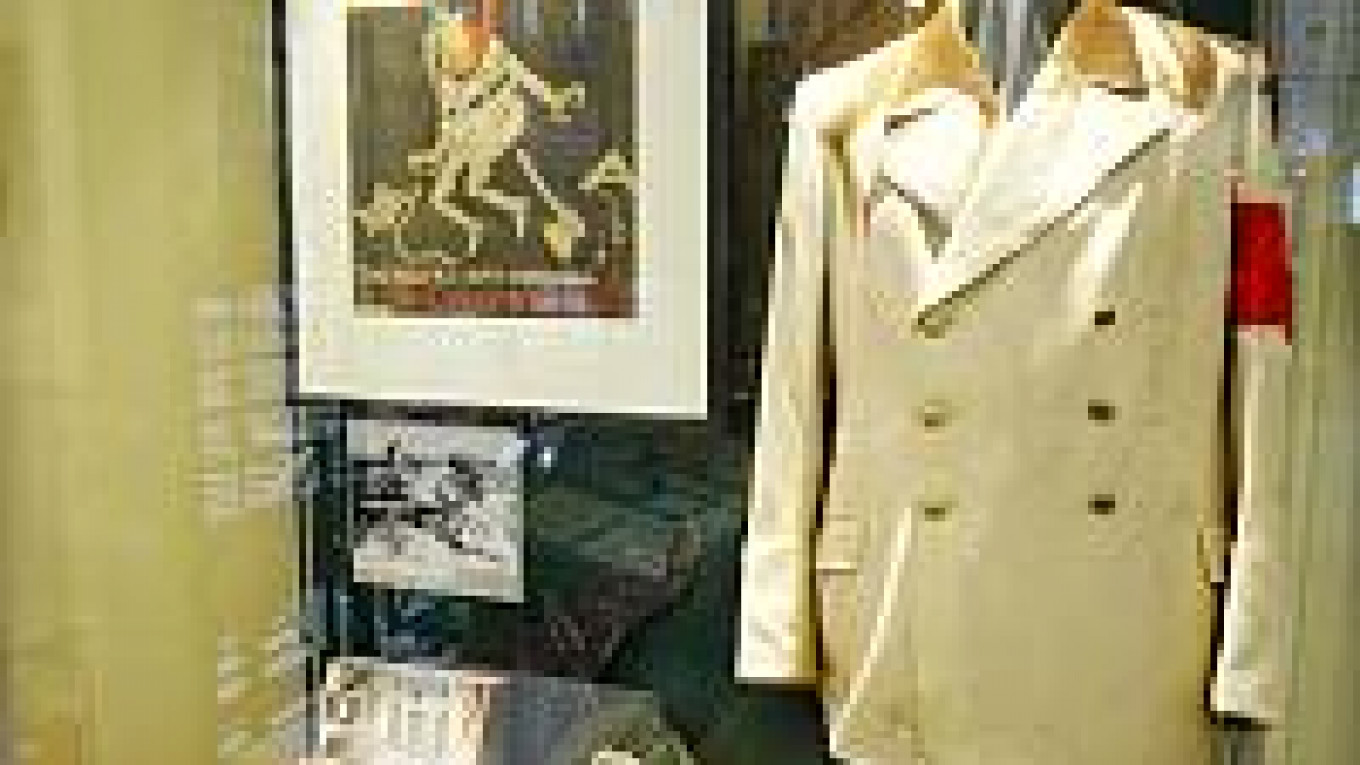

Standing next to a glass case containing Abakumov's white general's jacket and the text of Stalin's order creating SMERSH, Kozhin said that when the name of the new body was discussed at a meeting, someone proposed calling it "Death to German Spies," or SMERNESH as an acronym.

"Stalin said it was not only German spies we would have to fight, and the word 'German' [and the syllable NE] was taken out," Kozhin said.

Thus it became SMERSH, short for smert shpionam.

A SMERSH network with broad powers was created within the armed forces, with 21 men at the division level and one informer per every 10 soldiers.

Up until 1942, enemy saboteurs, if caught, were shot on the spot, Kozhin said. But then the policy changed and SMERSH officers successfully re-recruited many German spies. Several stands at the exhibit are dedicated to the so-called radio games that SMERSH played with the Abwehr, using captured German spies to lure others.

SMERSH takes credit for discovering the bodies of Nazi leaders, identifying them and then hiding the remains. Declassified documents shown at the exhibit tell the story of how SMERSH and its successors in the Soviet Group of Forces in Germany buried boxes containing the remains of Hitler, Eva Braun and the Goebbels family and their dogs in several secret locations. In 1970, when the Politburo decided to destroy the remains forever, they were dug up, incinerated and the ashes thrown into a river.

Yet Hitler's jaw, which was brought to Moscow back in 1945 for identification, remains in the FSB archives. Kozhin said the exhibit organizers had originally thought of bringing it over to the museum, but then reconsidered. "It is the only remaining part of Hitler's body. Imagine how much it could cost." he said.

The statistics cited at the exhibit are perhaps most telling of the censored picture it presents of SMERSH activities. During the war, military counterintelligence captured about 30,000 German spies, 3,500 saboteurs and 6,000 terrorists, according to the exhibit.

Nikita Okhotin, a historian and member of Memorial, a human rights group that researches Stalin-era repression, said he knows these statistics from Abakumov's May 1945 report to Stalin. But there are other, much bigger figures in that report that show SMERSH's broader role in political repression, he said.

The total number of arrests made by military counterintelligence from 1941 to 1945 was 627,636, Okhotin said, reading from the report, a copy of which Memorial had received from FSB archives. About 121,000 people were arrested for taking part in "counterrevolutionary organizations and groups," 135,000 for desertion and 84,000 for "anti-Soviet agitation."

According to another document, 66,500 people -- or twice as many as the number of spies SMERSH claimed to have caught -- were shot by firing squad as a result of its investigations, he said.

"The main function of SMERSH was looking for those who were unhappy and spreading panic, and enforcing discipline in the army," Okhotin said. "In the liberated territories, they were in charge of Soviet-style deNazification. The picture of SMERSH as a heroic force is at best incomplete and at worse falsified."

In spring 1946, SMERSH ceased to exist and military counterintelligence was given back to the security ministry.

The exhibit, which runs through Sunday, is open every day from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at the Central Museum of the Armed Forces, 2 Ulitsa Sovetskoi Armii.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.