In May 1913, impresario Sergei Diaghilev made Russian ballet famous by bringing a daring new production to Paris and nearly causing a riot.

People packed the Theatre des Champs-Elysees for the May 29, 1913, premiere of Igor Stravinsky's ballet "The Rite of Spring," whose irregular, modernist music threw some spectators into raptures and others into a rage. At one point, a brawl broke out and the police came, managing to restore only limited order to the crowd.

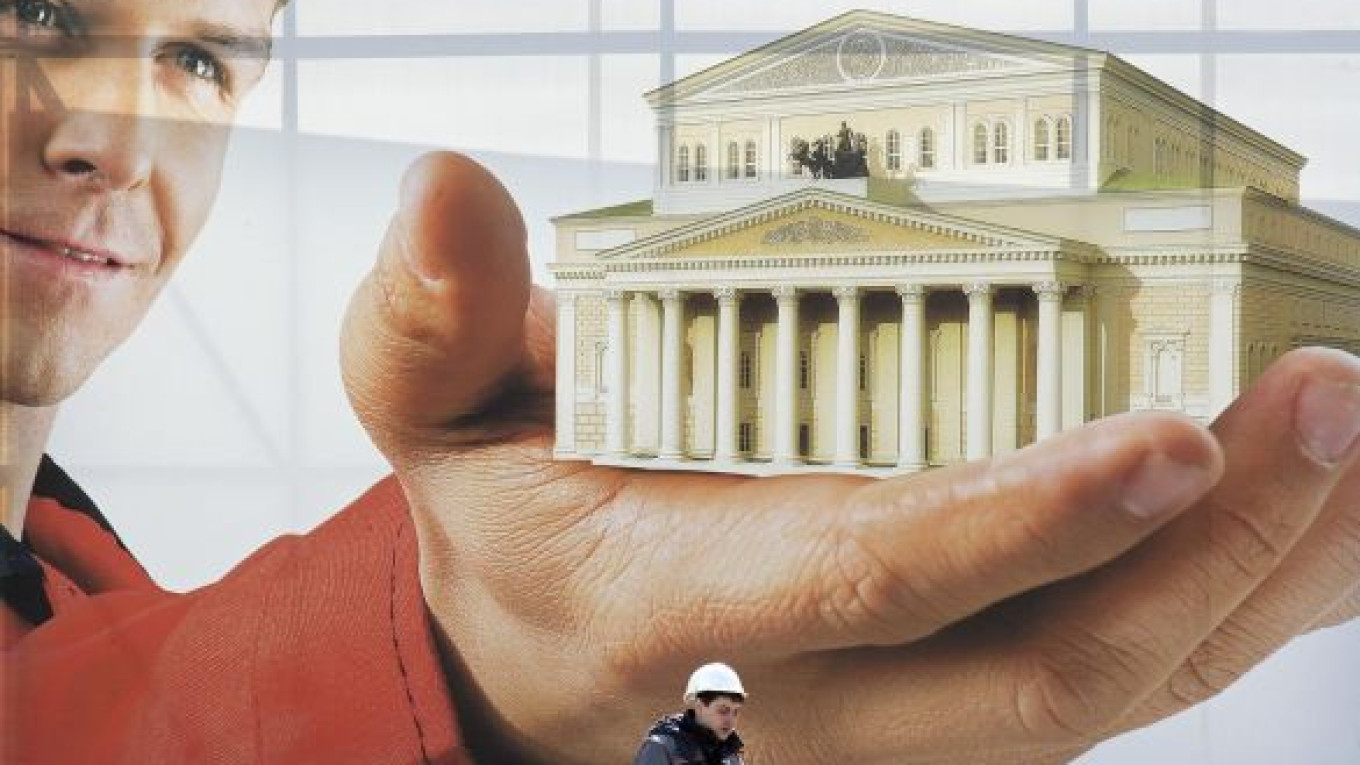

A century later, Russia's foremost ballet company, the iconic Bolshoi Theater, would love to cause the kind of uproar that Diaghilev did.

Instead, in recent months the theater has made headlines around the world for its behind-the-scenes intrigue and alleged mafia ties, after the ballet's artistic director Sergei Filin received third-degree burns when an attacker threw sulfuric acid on his face outside his apartment building.

With a Bolshoi dancer implicated as the organizer of the attack and a fierce struggle for control of the theater breaking into the open, the scandal is unlikely to die down soon, and observers say the theater's reputation could end up being significantly tarnished.

"This kind of attack is unprecedented in the ballet world, and the fact that someone from the company was involved in it reflects the way things are organized internally at the theater," said Raymond Stults, a Moscow-based ballet expert and a contributor to The Moscow Times.

The Bolshoi, founded by a Tatar prince and an English entrepreneur in the late 18th century, has long been one of Russia's most recognized institutions.

It was from the Bolshoi's stage that the formation of a new country — the Soviet Union — was proclaimed in 1922, while in August 1991 the Bolshoi's version of "Swan Lake" was played in a continuous loop on state TV to avert people's attention from the ongoing coup, masterminded by the decaying KGB. The ballet became a symbol of the demise of the Soviet empire.

The Bolshoi's history-fueled fame has apparently not diminished. According to Mikhail Sidorov, a member of the theater's executive board of trustees, a 2005 survey put the Bolshoi third on a list of the most famous symbols of Russia, behind only "U.S.S.R." and "KGB."

"The Soviet Union and the KGB are gone now, so the Bolshoi is the only world-famous brand we have left," Sidorov said.

President Vladimir Putin's spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, said earlier this month that the acid attack scandal likely wouldn't make an impact on the Bolshoi's image, given the theater's status as a "a longstanding symbol of Russian culture."

Stults said the Bolshoi was "so arrogant that it seems not to be concerned about its image," but there were signs that the theater had recognized the peril the scandal poses.

After giving Western journalists access to the theater's practice rooms and backstage to interview dancers in the weeks following the acid attack, Bolshoi spokeswoman Katerina Novikova refused a similar request earlier this month, saying reporters had used the opportunity to ask about the assault instead of focusing on Bolshoi productions.

"The press only looks for negative comments, as they get multiplied by numerous rumors," Sidorov said. "We can only counter this with what we have been established for: producing more excellent operas and ballets."

Earlier this month, Bolshoi director Anatoly Iksanov held a press conference to kick off the theater's celebration of the 100th anniversary of "The Rite of Spring" performances in Paris, which the Bolshoi is honoring by staging famous productions of the ballet to show its evolution over the last century.

The festival has suffered at least one consequence as a result of the attack, however: On Feb. 3, world-renowned contemporary choreographer Wayne McGregor said he would postpone his production of "The Rite of Spring" at the Bolshoi due to Filin's absence.

McGregor was replaced by Tatyana Baganova, a pre-eminent Russian choreographer, who was hired by the Bolshoi to create a new production in just a month's time. Her version was set to premiere on Thursday.

The theater has also begun to use modern PR techniques to increase its global reach, starting a Facebook page and broadcasting Bolshoi productions to 600 movie theaters around the world.

The ballet company will also go on tour this summer to New Zealand and Australia, then to London's Covent Garden, where the Filin incident has been "disastrous" to the theater's image, according to David Jays, editor of the Royal Academy of Dance's magazine, Dance Gazette.

He said audiences flocked to the Bolshoi's most recent London seasons in 2007 and 2010, when the troupe starred dancers Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev, formerly two of the Bolshoi's best-known stars, whom Jays called "phenomenal artists."

The pair left the Bolshoi for St. Petersburg's Mikhailovsky Theater in December 2011, dealing a major blow to the theater that made them famous. They cited "artistic freedom" as the reason for their departure, but many observers said that Mikhailovsky director Vladimir Kekhman, a tycoon known as the "Banana King" for his fruit import business, offered them a more lucrative deal.

"It is telling that [they] have since left the Bolshoi," Jays said. "Clearly the company no longer represents a classical dancer's ultimate goal."

Conflicts have flared inside the Bolshoi for years, including several in the last decade tied to a persistent rift between the theater's management and some of its leading artists.

Soloist Nikolai Tsiskaridze and former Bolshoi dancer Anastasia Volochkova have led the charge against Iksanov, accusing him of mismanagement and causing bad press for the theater. Iksanov has dismissed the allegations, saying ballet is a very competitive art and the criticism is the result of artistic rivalry.

Earlier this month, Volochkova renewed accusations that the Bolshoi administration had pimped out dancers, withholding privileges like foreign trips if they refused to have sex with wealthy patrons, and Tsiskaridze said he would be prepared to take over the director job if he were offered it.

Critics and supporters of Bolshoi's current leadership have vehemently argued about numerous issues in recent years, including the dancers' pay system, the theater's $1.1 billion reconstruction, which suffered chronic delays, and whether Bolshoi productions should become more modern or stick to their classical roots.

The dancers have also staked out positions on the acid attack on Filin, with many of them signing a letter in support of soloist Pavel Dmitrichenko, who has been accused by police of ordering the attack. Filin has said that Dmitrichenko, who partially confessed to being behind the assault, was one of the people he suspected, while both the troupe and the Bolshoi administration have said they think Dmitrichenko was a puppet acting at someone else's behest.

Bolshoi Ballet principal dancer Marianna Ryzhkina, who has been at the theater for more than two decades, told The Moscow Times that despite the media pressure, the theater was "very strong" at the moment and its artistic achievements would eclipse the scandal. "Unfortunately, this situation is just a reflection of what is going on in the world in general," she said.

Ryzhkina's explanation was echoed by Vadim Gayevsky, a ballet critic who has attended the Bolshoi since the Stalin era. "Theater is always a replica of reality, where life's passions are only exemplified," he said.

"It is wrong to separate the Bolshoi from the rest of our country. On the contrary, we actually observe what happens in Russia by looking into the way the Bolshoi works."

Gayevsky said the Bolshoi's main problem is its lack of a strong artistic leader. Asked who could fulfill such a role, he suggested Alexei Ratmansky, the Bolshoi Ballet's artistic director from 2004 to 2008, who wrote recently on his Facebook page that the Bolshoi situation makes him "sick."

Jays, the editor of Britain's Dance Gazette, said Ratmansky told him in an interview earlier this year that the Bolshoi had always been a symbol to the outside world of the Russian body politic — whether of imperial Russian assertiveness or of Soviet triumphalism — and that recent events were emblematic of a debased and deeply corrupt public culture.

"Even if there are reforms within the theater itself — and it seems the reforms would have to be widespread and profound — the broader problem would remain," Jays said.

But the Bolshoi has seen its share of tumult over more than two centuries, and for now, audiences have not abandoned it. Novikova, the Bolshoi spokeswoman, said she wasn't aware of any change in ticket sales since the attack on Filin, adding that the theater's two auditoriums were as full as ever.

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.