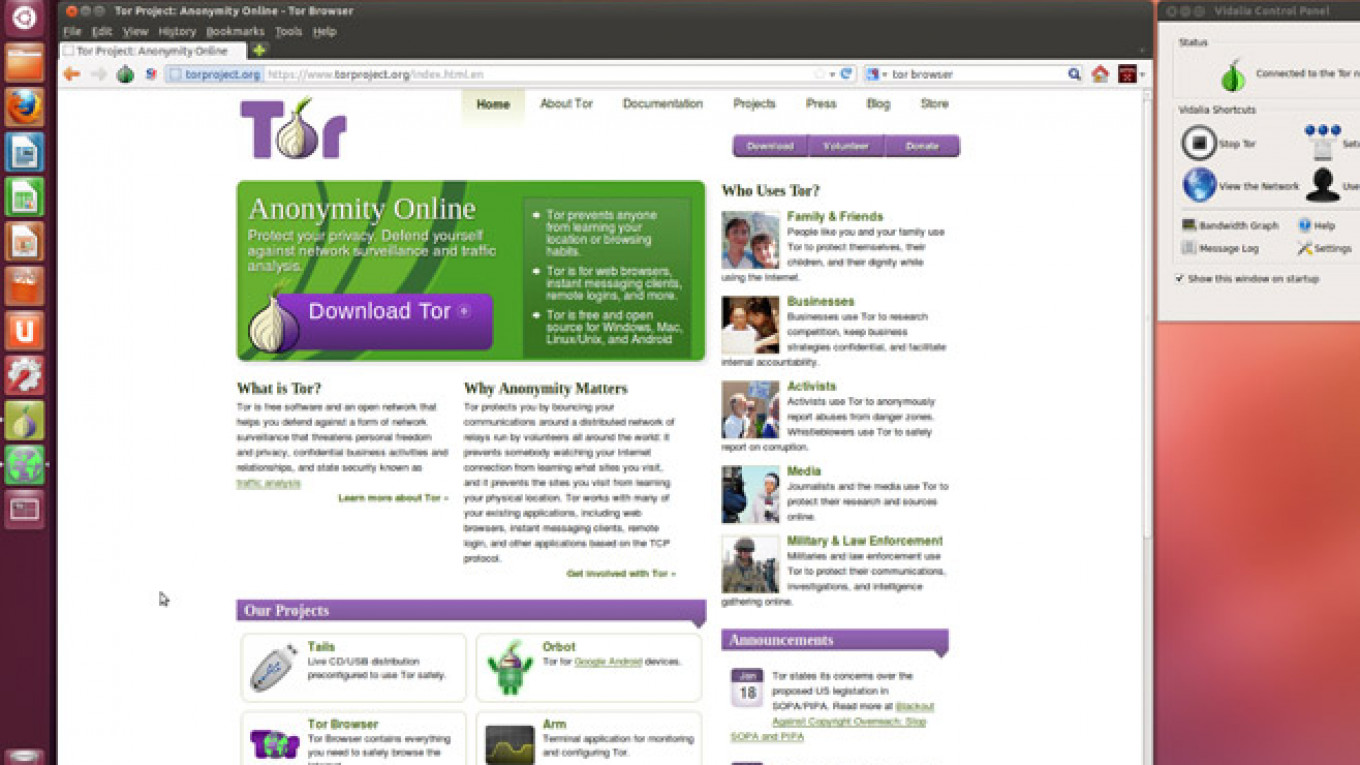

The government's campaign for online censorship has created a backlash, with the number of Russia-based users of anonymous web surfing software Tor more than doubling in the past three weeks.

The Tor network, which allows users to anonymously visit websites blocked in their country, numbered almost 200,000 users from Russia on Wednesday, compared to some 80,000 as of June 1, according to official statistics for Tor usage on Torproject.org.

This is the second such upsurge: The number of Russian Tor users previously shot up from 25,000 to 150,000 between mid-August and mid-September 2013, according to official data, before decreasing again.

The current figure is still a fraction of Russia's multimillion netizen army.

But Tor usage is likely to skyrocket if the authorities begin to actively enforce Internet censorship legislation, now applied only sporadically, Internet experts said.

"People are waking up to the fact that the government is hamfistedly regulating the Internet, and are increasingly looking for tools to regain access to information," said Artyom Kozlyuk of the independent Internet freedom watchdog Rublacklist.net.

The Kremlin, which largely neglected the domestic segment of the Internet during its explosive growth in the 2000s, has ramped up oversight since 2012. (See timeline below for details.)

Russia had 68 million Internet users as of last winter, or 59 percent of the adult population, according to the state-run Public Opinion Foundation. In 2004, that figure was 11 million.

Initially nonpolitical, the regulatory drive has recently seen the blacklisting of prominent anti-Kremlin websites, including the LiveJournal blog of leading opposition politician Alexei Navalny.

A mounting anti-piracy effort is also ongoing, and may account for the current upsurge in Tor usage, Kozlyuk said.

In late May, the State Duma discussed a sweeping copyright protection bill that proposes extrajudicial blacklisting of websites suspected of hosting pirated music, books or software. The bill is currently pending a second reading.

Officials, including President Vladimir Putin, have repeatedly pledged to uphold the constitutional ban on censorship.

But experts and Internet freedom activists polled by The Moscow Times said the government is working to introduce online censorship in Russia, though they doubted whether it would succeed.

"They are enemies of freedom of information," said Anton Nosik, a popular blogger and entrepreneur who was behind many of Russia's leading online media.

"But all they will achieve is an increase in the public's computer literacy," Nosik said by telephone.

Political censorship may in fact be effective, as most Internet users are unlikely to bother circumventing such bans, said Stanislav Shakirov, co-founder of the unregistered Pirate Party of Russia.

The anti-piracy effort will likely be a more efficient popularity booster for Tor and other anti-blacklisting software, Shakirov said. A July 2013 anti-piracy law accounted for the previous surge in Tor usage in Russia, he added.

About 49 percent of Russians considered Internet censorship acceptable, while 23 percent were wary of it and 29 percent had no opinion, according to an April poll by the independent Levada Center.

But Nosik said Russia is more likely to follow the path of Iran, another censorship-heavy nation where, nevertheless, "every last peddler knows his anonymizers."

Iran, notorious for blacklisting websites such as YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, was included on the "Enemies of the Internet" list by Reporters Without Borders in March. However, a 2012 survey by local online research panel Chimigi showed 58 percent of Iranian web surfers used Facebook despite bans.

The censorship effort in Russia has yet to affect any really popular websites such as Facebook, said Kozlyuk of Rublacklist.

But millions will make use of anti-censorship software if their favorite online domains are hit, he said.

"Technology is always a step ahead of any repressive legislation," Kozlyuk said. "And users will always find a way to access a website they have grown to frequent."

Milestones of Internet regulation in Russia:

• 2012, November: Extrajudicial blacklisting allowed for websites promoting child pornography, suicide and illegal drugs. Data from Rublacklist.net indicates 97 percent of websites on the list committed no offense and were banned as the collateral damage of imperfect blacklisting methods.

• 2013, July: Extrajudicial blacklisting expanded to websites accused of hosting possibly pirated films.

• 2013, October: The Pirate Party of Russia, which campaigns for freedom of information, denied official registration for the third time over its title, which, the government claimed, promotes "robbery on the high seas."

• 2014, February: Extrajudicial blacklisting expanded to websites accused of promoting riots as well as extremism, a charge frequently applied to critics of the government.

• 2014, June: Bloggers with a daily readership upward of 3,000 users obliged by law to de-anonymize and register with the state.

The authorities have also discussed bans on Facebook and Twitter and tighter rules for news aggregators such as Google and Yandex, as well as extrajudicial blacklisting of online retailers of counterfeit alcohol and websites featuring allegedly false banking information or, separately, expletives.

See also:

Russia Presents New State-Owned Search Engine Called Sputnik

Contact the author at a.eremenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.