A few years ago in an interview with Western journalists, President Vladimir Putin made a statement that was so strange people thought it was a joke. "It is my misfortune … [and] tragedy that I am alone. There just isn't anyone else like me in the world. After Mahatma Gandhi died, there was nobody left to talk with."

Actually, Putin chats with Syrian President Bashar Assad, the leaders in Iran and other people Gandhi would clearly never have spoken with. But there is a small bit of truth in what Putin said. The world really doesn't listen to Putin. People only hear what they want to hear, and that is whatever doesn't upset them. Back in 2005, Putin said that the dissolution of the Soviet Union was "the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century." Many people only remembered these words when it became clear that "fixing" the results of that catastrophe — at least in part — has become Russia's top foreign policy strategy.

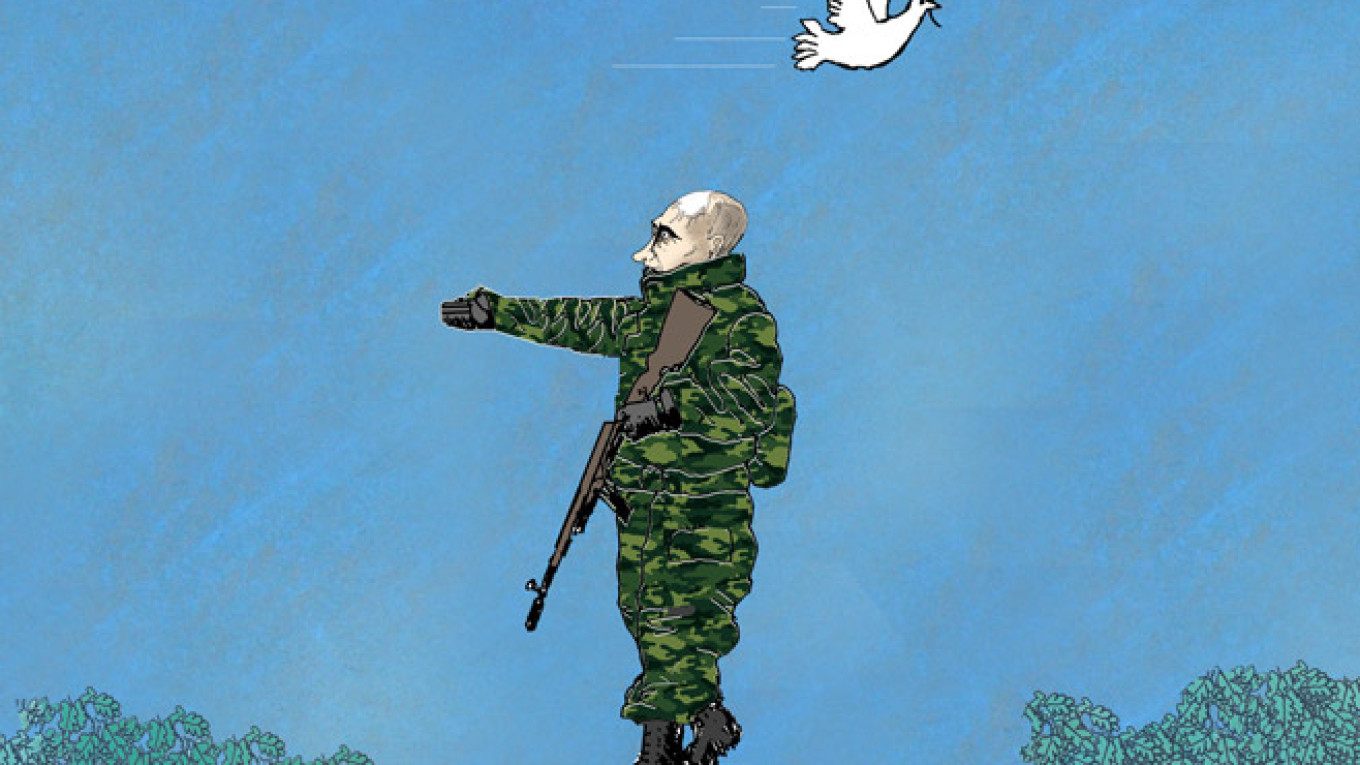

Buried in the usual official niceties of the two speeches Putin gave to commemorate Victory Day on May 9 in Moscow and Sevastopol were several important messages. Addressing the world, Putin asked everyone to respect "our legitimate interests, including the restoration of historical justice and the right to self-determination."

But self-determination does not apply to ethnic groups within Russia, where "promoting separatism" was recently made a felony. And Russia's "legitimate interests" include former Soviet republics, where Putin, in violation of international law, has been "restoring historical justice" as he sees fit.

It is interesting to compare Putin's speech at the May 9 parade in Moscow with the speech he gave a year ago. Last year, he ended with a call "to overcome all difficulties and obstacles and pass on to our children a prosperous, free and strong Russia." This year, "prosperous" and "free" were gone. In their place were calls to "place service to the fatherland above all" and to "defend the interests" of Russia.

The difference between this year's "defending Russia's interests" and last year's "defending the homeland" is significant. The difference can be understood from the text of the law on veterans. Out of the list of 49 wars that the Soviet military fought in the 20th century, only in World War II did Soviet soldiers defend their country from invasion. All the rest of the wars took place on foreign territory. The list includes the suppression of the Hungarian uprising of 1956, the war in Korea, military operations in Egypt during the Six-Day and Yom Kippur Wars. It also includes military operations in Vietnam beginning in January 1961, when U.S. President John F. Kennedy was still categorically opposed to sending U.S. troops into the conflict.

The change from last year's concept of patriotism to this year's notion of "defending the interests" of your country was hard to miss. Journalist Aider Muzhdabayev wrote in his blog on the Ekho Moskvy website: "As you look at those people who are calling for a new war, you realize that this is a betrayal of the memory of the dead frontline soldiers and an insult to the living. But for some reason this is called patriotism."

Remarkably, despite the titanic efforts of the state propaganda machine, the concept of patriotism among Russians is moving in the complete opposite direction. A poll conducted Feb. 21-25 by the Levada Center among 1,603 Russians showed that the number of people who agree that a "patriot should defend the country from any kind of insults and criticism" has dropped by 6 percentage points since 2000 from 24 percent to 18 percent. At the same time, the number of respondents who understand patriotism as the personal feeling of love for one's homeland increased by 10 percentage points from 58 to 68 percent. And the number of people who do not agree with the statement that "a patriot should support the authorities no matter what" is almost twice the number of people who agree, 65.3 and 23.3 percent, respectively.

Even more remarkable are the changes in public opinion about Ukraine. In another Levada Center poll conducted March 24 among 1,602 Russians with an error margin of no more than 3.4 percent, 25 percent of respondents were certain that Russian military boots on the ground would stabilize the situation in Ukraine. By the end of April, when the poll was repeated, only 11 percent thought Russian presence would bring stabilization. In both months, 14 percent were certain that a Russian military presence would set off a conflict with unpredictable consequences.

Those public opinions were crystallized by rock musician Yury Shevchuk. He wrote on his Facebook page: "My position rests on peace that embraces everyone with civil rights and social justice. On May 9, I will go to church to pray and light candles in memory of all those who died in Kiev, Slovyansk and Odessa."

Ultimately, the notion that human life takes priority over state interests has always been victorious everywhere. But all too often, the path to that understanding goes through war. Unfortunately, today as we observe tens of thousands of Russian troops on Ukraine's border and the mayhem unleashed by pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, it is hard to believe that this time the path will be easy.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist who follows the Russian blogosphere in his biweekly column.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.