He studied little while in Chechnya due to the military campaigns. When he moved with his family to Moscow last year, he quit attending school after six weeks to escape his classmates' taunts.

He speaks very much like Movsar Barayev, the leader of the group of hostage-takers. His words come out slowly and awkwardly as he tries to put them together.

His brothers went to the same school as Barayev, and he says he would have joined the rebels if his mother had not moved to Moscow.

"I regret only one thing now -- that I am not there beside Movsar," Shamkhan said Tuesday. "He stood up for our nation."

Shamkhan and Barayev are among a new breed of young Chechens who have scant respect for their elders and even less for the Russian authorities, experts said. They were raised during the 1994-96 military campaign and witnessed the brutality of the ongoing clash, which recently entered its fourth year. The collapse of the social order and centuries' old tradition in Chechnya has made them easy prey for extremism.

"Children who grow up in military conflicts have a very polarized perception of the world -- everything is black and white in their minds, everyone is either friend or foe," said Sergei Yenikolopov, a prominent Moscow psychologist.

A Chechen man brandishing a gun and liberating his homeland from Russia has become a hero in the eyes of Chechen children, said Shamil Beno, a foreign minister in the government of late Chechen President Dzhokhar Dudayev.

"This is absolutely normal for children since Russia carpeted Chechen towns and villages with bombs [in the first war]," he said.

"Those who are now 23 to 24 years old, the same age as Movsar Barayev, sucked in all the negative things of that period," said Kheda Omarkhadzhiyeva, a Chechen psychologist who counsels victims of the conflict.

"It was the most sensitive age, and they took whatever they saw as their ideals -- violence and people with weapons," she said. "I think the dominating feelings are for revenge and justice. These feelings are stuck in them because they haven't seen anything else but violence, and no one was really helping these boys out."

After the first war, Russian television several times aired footage of Chechen boys in military uniforms marching in parades for Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov. Today, those boys are believed to form the most violent part of the rebel cause, and convincing them to accept a peaceful life will be next to impossible, Yenikolopov said.

Furthermore, their ranks could grow as young Chechens continue to see family and friends humiliated, beaten and killed by Russian troops, experts said.

Beno said his 21-year-old nephew lost a leg in a Russian bombing in Chechnya. The young man enrolled in Grozny University this year but has already stopped attending classes because he no longer could bear the frequent stops and searches by soldiers, Beno said.

"Now the boy has a clear understanding of who is his enemy," he said.

War has broken traditions -- such as respect for the elders -- that once brought strict discipline and order to Chechen society, Yenikolopov said. Having taken up arms, young Chechens have felt the power of being able to decide for themselves who is going to live and who is going to die, he said.

This new way of thinking was witnessed by State Duma Deputy Iosif Kobzon when he attempted to negotiate with Barayev and his group.

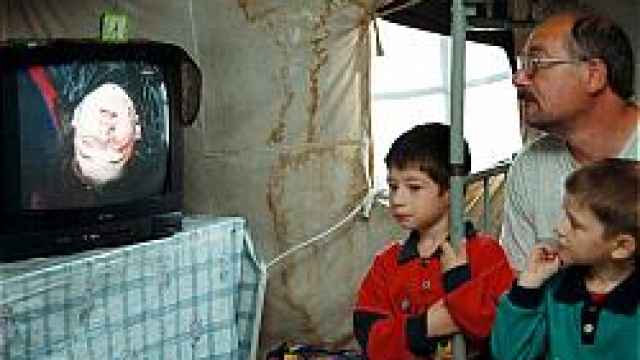

Musa Sadulayev / AP Chechen refugees in Ingushetia watching footage of the theater raid on Saturday. | |

After breaking with tradition, many young Chechens became involved in criminal activities such as hostage-taking, which quickly earned them large fortunes in the impoverished republic. That taught the youth to measure success by the number of Mercedes or guns a man owned, Beno said.

Barayev belonged to a clan of those young Chechen elite. His uncle Arbi Barayev -- who was killed by Russian troops at the age of 27 last year -- was the head of the clan and had no qualms about ignoring orders from Maskhadov to release hostages.

The collapse of the education system in Chechnya after the beginning of the first war further alienated young Chechens from Russia, which had provided textbooks and schooled Chechen teachers and professors.

"It is hard to estimate the illiteracy rate among children in Chechnya," said Omarkhadzhiyeva. "In a single grade, you can find children with very different levels of education."

Without an education, it almost impossible to prepare Chechen youths to lead normal lives, Yenikolopov said.

"Peace provides more opportunities to the educated, and what can be offered to young Chechens who are educated only in warfare?" he said.

The vacuum left by ruined traditions and a lack of education has been filled by Wahhabism, a simple but aggressive brand of Islam, said Dmitry Makarov, an Islam expert at the Moscow-based Institute of Oriental Studies.

"This kind of Islam has helped make the protests of Chechen youth against the Russians become a holy war against infidels," he said.

In their last interviews, Barayev and his group declared they had come to Moscow at Allah's will. Female commandos were shown wearing black headbands with Arabic verses from the Koran.

"Islam helps young Chechens justify their independence from their elders and anybody else," Makarov said. "They believe they are under the command of Allah alone."

Shamkhan, the 17-year-old boy, comes from Argun, the same town where Barayev grew up. He has two older brothers; the eldest was in the same grade as Barayev and was killed by a Russian missile in 1999.

The middle brother took judo classes with Barayev. "Movsar was a good person. He never drank, took drugs or even smoked," the brother said.

"He did not study that well, but not too bad either," he said. "I can't say that he was illiterate. And he was really determined to fight for freedom."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.