By Joseph Backstein for Calvert Journal

It was raining on Sept. 15, 1974, the day of the so-called Bulldozer Exhibition. I remember the long walk to the open-air venue — a field — from the nearest metro station, Belyayevo, with my wife and our newborn daughter Lena.

The organizers — artists Oskar Rabin and Yevgeny Rukhin — along with others had deliberately chosen an outdoor space for the show, some wasteland on the edge of the city that would be too far away to be of interest to the security services but would still be easily accessible by those invited to attend. It goes without saying that if the exhibition had been held in one of the city parks, it would, without fail, have come under very close scrutiny by the KBG.

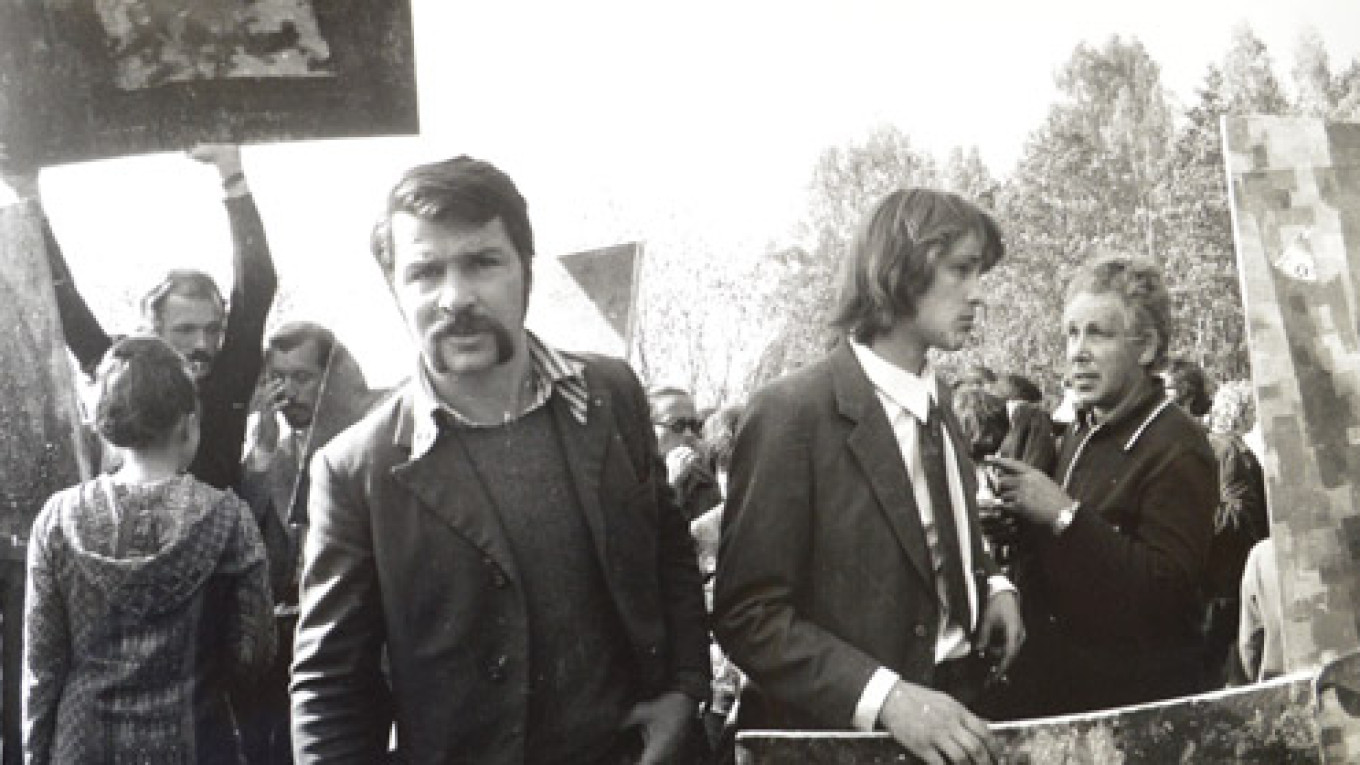

We were running late and when we finally arrived, there was mayhem: Artists were running around the field in a desperate attempt to hide their paintings from the thugs who had been hired by the local authorities. It was a horrific scene: These young "civil servants" were throwing artworks into trucks and using bulldozers to crush them.

What these hired hooligans didn't realize though is that they were surrounded by dozens of international journalists who filmed the carnage from beginning to end.

Some of the journalists were beaten up, but most managed to escape. In the end, the crowd, which had already been soaked by torrential rain, was dispersed by high-pressure hoses mounted on street-cleaning trucks, which resulted in an interesting official version of events. The Soviet authorities presented the crackdown as a state-sanctioned cleanup of the park.

Apparently, the KGB knew about the show anyway, which hardly came as a surprise to us. At that time artists who didn't belong to the official union of artists were treated with suspicion. Their phones were tapped, and they were under constant surveillance.

The independent artistic community was tiny and tight-knit, and they were all in attendance at the Belyayevo show. There were more than 30 artists present, including the most prominent figures in the community, like Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, Russian emigre conceptual artists.

Many of the artists who took part in the Bulldozer Exhibit later emigrated.

If it weren't for the strong international reaction, the bulldozer show would have been forgotten. As it turned out, the organizers invited every foreign correspondent they knew, and all of them turned up, making it one of the most documented events in the history of Russian contemporary art. The New York Times put the bulldozer story on their front page along with some Komar and Melamid paintings. These artists woke up the next day to find themselves known around the world.

And then something happened. Something that nobody had anticipated. The regime suddenly changed its mind about contemporary art. The first secretary of the local branch of the Communist Party — the man behind the crackdown — was fired; it seemed the government was keen to appease those involved in the arts.

That's not all. Out of the blue, there came a proposal from high-up Communist Party officials for the Moscow art community to stage the first-ever contemporary art show in the Soviet Union. The event took place on Sept. 29 in Izmailovsky Park in northeast Moscow. Most of the artists who had participated in the Bulldozer Exhibition two weeks earlier were now officially permitted to show their works to the general public.

I kept asking myself what happened? Why was there this sudden change of course? The foreign press did play a crucial role in legitimizing ?contemporary art in the Soviet Union, but there was already something brewing within the regime, a subtle new dissident movement that was slowly but steadily growing until it erupted in perestroika, which eventually lifted all the Kafkaesque barriers and constraints.

Although most of the "bulldozer artists" subsequently emigrated from the Soviet Union, their legacy is as tangible as ever. This brave, brief exhibition changed things permanently. I want to believe that there will be no return to those times of censorship and surveillance, regardless of all the recent conservative rhetoric.

The anniversary of the Bulldozer Exhibition will be commemorated by a new group show featuring young Russian artists and those who participated in the historic Belyayevo show 40 years ago. Symbolically the new show, "Freedom Is Freedom," will take place in the state-owned Belyayevo Gallery, just a stone's throw away from that gray and gloomy field that became an international symbol of artistic resistance and hope.

"Freedom Is Freedom" (Svoboda Yest Svoboda) runs until Oct. 12 at the Belyaevo Gallery. 100 Profsoyuznaya Ulitsa. Metro Belyayevo. 499-793-4121, 495-335-8322, gallery-belyaevo.ru

This article first appeared in the online magazine The Calvert Journal, a guide to a creative Russia.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.