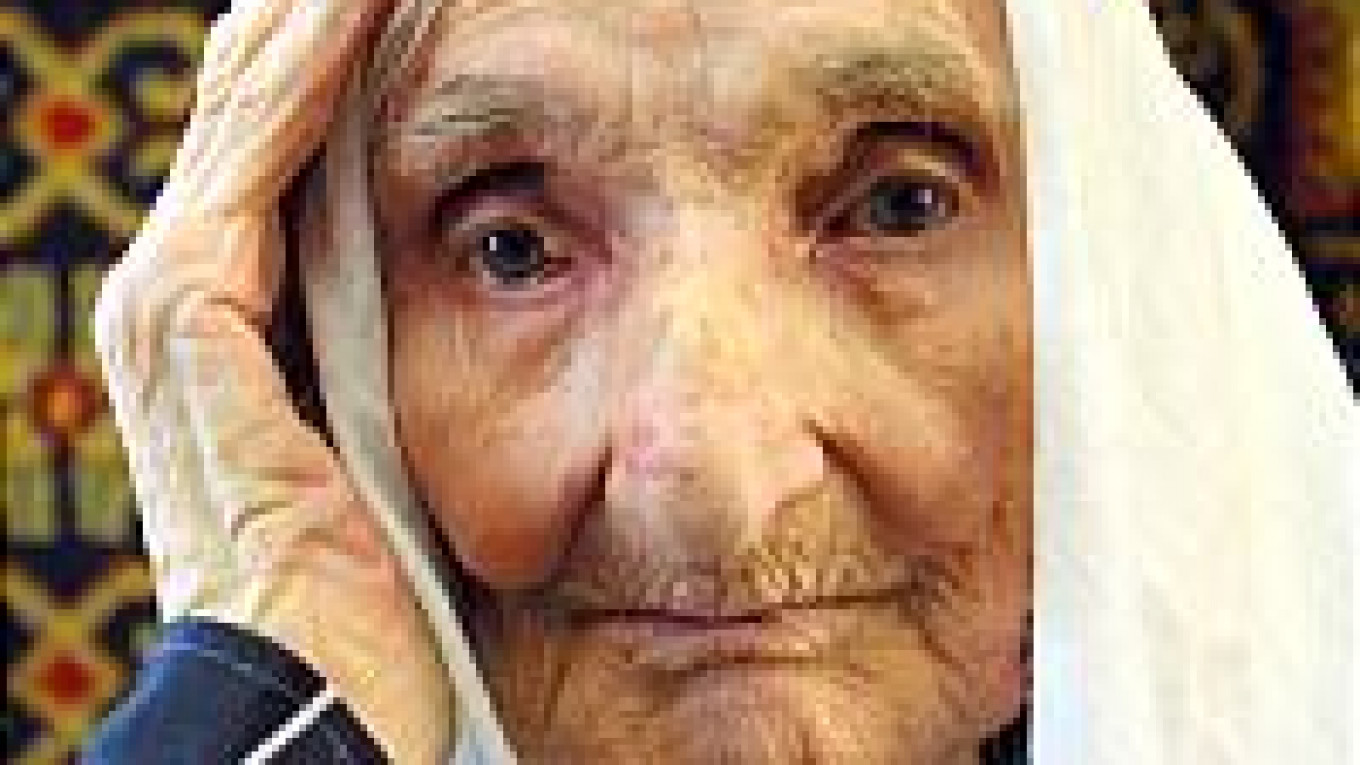

Dzhukalayeva, who could very well be the oldest woman in the world, also moves about the house by herself and has kept her eyesight sharp enough not to need spectacles.

"A person lives as long as the Most High wishes," she said in a recent interview.

The State Statistics Committee said there are two women in Russia who confirmed last year that they were 122 years old. Both live in Chechnya and were put on record during the 2001 nationwide census, said Lyudmila Yeroshina, a committee spokeswoman.

It's not clear if Dzhukalayeva is one of them, since the committee doesn't release the names and addresses of the people in its records.

Another long-living woman died in Chechnya at 124 last year, according to Yeroshina.

Yeroshina noted that the census data may not be entirely accurate, since census-takers do not require people's identification papers, writing down their information from their words alone.

The Gerontology Institute, which studies longevity, was unable to confirm the number of proven long-livers either. "We don't have a technique to establish exact age," said Zinaida Simina, head of the institute's laboratory for medical and social issues of gerontology.

Dzhukalayeva showed a passport to Rossia television stating that she was born in 1881, but Simina said it's hard to verify whether it was correct.

Since that date, Russia has gone through well-documented tumultuous times, including a revolution, a civil war and two world wars. In addition, Chechens suffered a sudden deportation to another Soviet republic.

However, Simina said most of Russia's longest-living residents come from the mountainous southern areas where the climate, especially the air, helps to prolong life.

The world's oldest women have so far come from outside Russia. According to the Guinness Book of Records, U.S. citizen Charlotte Benkner, currently 113 years old, is the world's oldest living woman. France's Jeanne-Louise Calment had been the oldest woman by documentation, before she died at 122.

Dzhukalayeva was born in Itum-Kali, a village perched high on a Caucasus mountainside. She lived there until 1944, when Stalin deported all Chechens to Kazakhstan. She later returned to her homeland.

Dzhukalayeva survived five brothers and sisters and four children.

Her granddaughter Yakha said Dzhukalayeva used to swim in cold mountain springs in her youth and later took cold showers every day. One of her other habits is not eating after 6 p.m.

"In Itum-Kali, night fell early, right after sunset," said Yakha. "Residents went to bed about 7 p.m. Hence the habit."

Until last year, Dzhukalayeva sewed things for her great-great-grandchildren, but her eyesight worsened and now she can't thread a needle, Yakha said.

Many landmark events of the past century passed unnoticed in her remote village.

If her age is correct, she was in her 30s during World War I and the 1917 Revolution, but she knew of the latter only a few years after it happened. "My husband, Vaid, went to Grozny to sell wood," she recollected. "He was told there that something had happened in St. Petersburg." She's still in the dark about exactly what it was.

World War II for her is associated with her three grandsons leaving for a period of time, returning to the family after the deportation.

The deportation left memories of what she called "ungrateful" Russian soldiers and strikingly different landscapes and faces in Kazakhstan.

She said the villagers were not aware that the soldiers arrived to escort them to their new and distant residence, and welcomed them as "the best guests." For the two soldiers who were quartered in their house, "we slaughtered two chickens and cooked several dishes."

"Knowing why they came and seeing our treatment of them, they didn't even warn us," she lamented. "We could have prepared and collected warm things."

In Kazakhstan, she said, locals were frightened by anecdotes that Chechens were cannibals, and at first kept their children at home. Quite a while passed before relations normalized and Chechens and Kazakhs began befriending each other, she said.

When she returned to Chechnya, she settled near Grozny, at a collective farm called Rodina. Dzhukalayeva has lost family members in the two wars prompted by Chechnya's independence bid.

Her sister Ashu, five years older, died in 1999 of a heart attack after she learned that federal troops had killed her 80-year-old daughter, Zareta.

These deaths bore hard on Dzhukalayeva, and she didn't leave the house for a long time, said Yakha. When she finally ended her seclusion, she fell and broke her leg. Doctors said that the fractured bone wouldn't heal, "but the grandma surprised everyone by walking again in a month," Yakha said.

Dzhukalayeva has little idea of why the current round of war started, she said, and she has a dual vision of Russia. On the one hand, she regards it as another country. But she also blames Moscow for delaying payment of her pension allowances.

She longs for an end to hostilities: "I very much want to live until the day when peace comes to Chechnya."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.