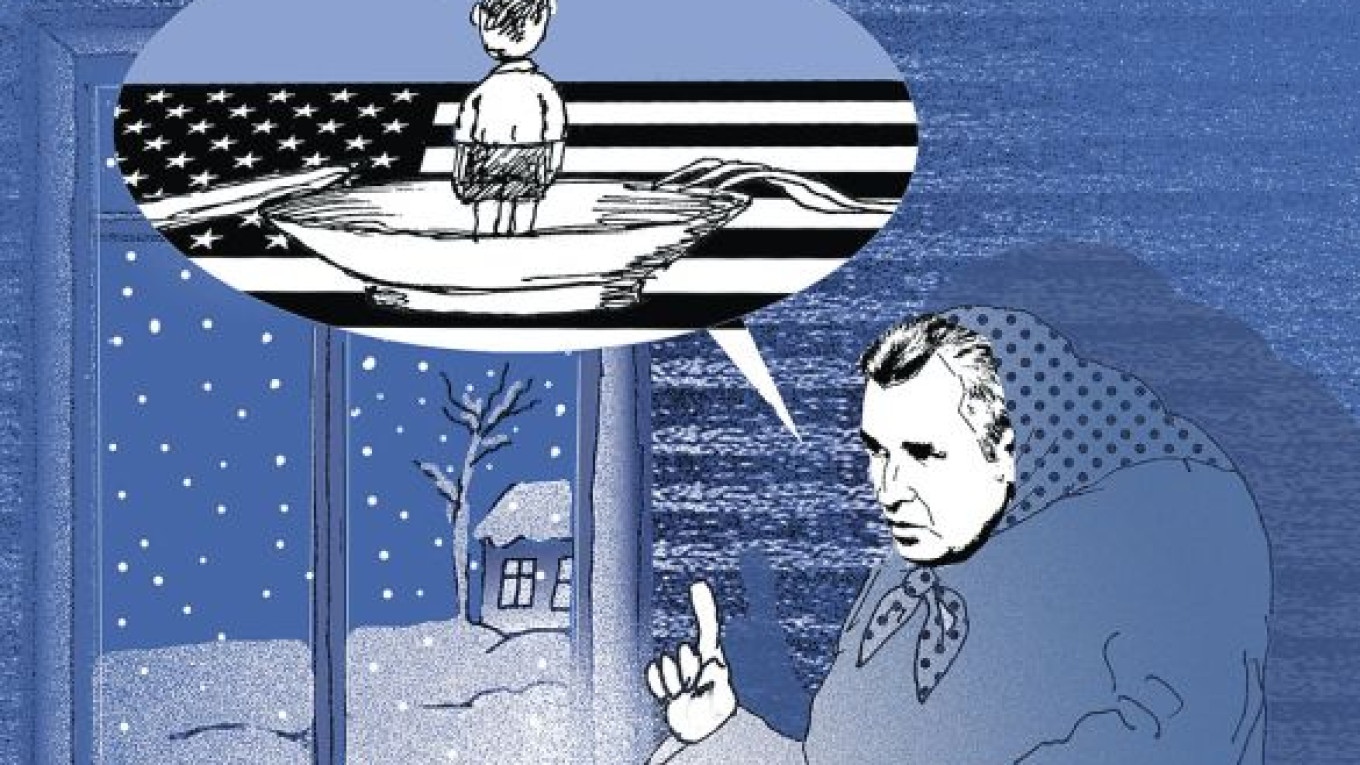

Russia's ban on U.S. adoptions has been accompanied by a massive propaganda campaign filled with many distortions and fabrications. Below are the 10 largest myths spread by children's rights ombudsman Pavel Astakhov, United Russia Deputy Vyacheslav Nikonov and other Kremlin propagandists, followed by the real story behind Russia's myths about U.S. adoptions:

Myth No. 1: Russia's orphans are in more danger in U.S. families than in Russian orphanages.

Over the past 20 years, there have been more than 60,000 U.S. adoptions of Russian children, and 19 of those children died — a death rate of roughly 0.03 percent. In Russia over the same period, there have been about 1,220 deaths out of more than 170,000 adoptions, or a death rate of 0.7 percent, according to the Education and Science Ministry.

If you look at the total number of child deaths by parents in both adoptive and birth families, it is estimated that there have been about 2,000 deaths each year over the past 20 years both in the U.S. and Russia, according to Konstantin Dolgov, the Foreign Ministry’s human rights commissioner who cited information from a U.S human rights organization, and.former children's ombudsman Alexei Golovan. This would mean that Russia's overall child death rate from parents is more than two times higher, given that the U.S. population is more than twice as large as Russia's.

Myth No. 2: U.S courts are soft on U.S. parents in child abuse cases if the children were born in Russia.

The Kremlin likes to focus on two highly publicized cases. One involves the death of 21-month-old Dima Yakovlev, in which his U.S. father was found not guilty of involuntary manslaughter after leaving Dima alone in a hot car for nine hours. The other case was Ivan Skorobogatov, whose adoptive parents served only 1 1/2 years in prison after being convicted of involuntary manslaughter. But in the overwhelming majority of other U.S. cases of involuntary manslaughter and child abuse involving adopted Russian children, the sentences exceeded nine years.

Sexual abuse cases, in particular, tended to carry heavy sentences. Matthew Mancuso, for example, was given a 35-year sentence in 2007 for sexually abusing his adopted daughter, Masha Allen, who was born in the Rostov region.

Myth No. 3: Judges and juries are anti-Russian.

In many child abuse cases, the issue of where the children were born was mentioned only briefly in court as part of their biography. After all, the victims were U.S. citizens, and the defendants were tried for crimes against U.S. citizens. In the Dima Yakovlev case, for example, the child was referred to in court by his American name, Chase Harrison. The main question before the jury was whether the father was guilty of involuntary manslaughter by leaving his adopted child in a car. The child's country of birth, Russia, was completely irrelevant to the case.

In the case of Ivan Skorobogatov ?€” referred to in court by his American name, Nathanial Craver ?€” the defense and its expert witnesses had to explain to the jury that the child consistently displayed severe self-destructive behavior as a result of fetal alcohol syndrome. But Nathanial could just as likely have been born in Moldova, the Czech Republic, Finland or any other country with high alcohol consumption rates and levels of fetal alcohol syndrome. There was nothing uniquely Russian about Nathanial's case.

Myth No. 4: Russian parents adopt more children with disabilities than U.S. parents.

In 2011, U.S. parents adopted 89 Russian children with disabilities, while Russians adopted 38, according to Social Affairs Minister Olga Golodets. This 2.5-to-1 ratio has remained consistent over the past 20 years. With the ban on U.S. adoptions, Russia will now be able to boast of a 38:0 score against the U.S. But the nearly 100 disabled orphans whom U.S. parents once adopted every year will lose out big on this fixed match; many will not live to be 18 in Russian orphanages.

Myth No. 5: There are more Russian parents who want to adopt children than there are orphans available, but U.S. parents have "crowded them out."

There are roughly 650,000 orphans in Russia, with about 120,000 of them "available for adoption" each year, according to Astakhov. Russian parents have adopted about 8,000 children a year on average since 1992, while U.S. parents have adopted about 3,000 of them a year. This means that there is a net surplus of more than 100,000 Russian children available for adoption each year. Thus, the reason Russian parents do not adopt children has nothing to do with U.S. parents "monopolizing the Russian market"; they occupy only 2.5 percent of the available adoption pool. The reason probably has more to do with the fact that adoption as a social institution has still not recovered since the Soviet Union destroyed the church ?€” and charity along with it. What's more,? the economic inability of many Russians to support an adoption, particularly when the children suffer from psychological and physical disabilities, plays an equally important role.

Myth No. 6: When U.S. parents get fed up with rearing adopted children from Russia, they send them to U.S. ranches to get rid of them for good.

These ranches, staffed with psychologists and other professionals, are designed to help children with serious behavioral problems that are often the result of abuse and neglect they incurred in orphanages, or from problems they inherited from mothers who abused drugs or alcohol during pregnancy. The cost of these camps ranges from $3,500 to $7,000 a month. There are few U.S. parents who could afford to "get rid" of their Russian children by paying more than $60,000 a year until the child turns 18. It would be much easier ?€” and less expensive ?€” for parents to give their Russian adoptees up for adoption in the U.S., even if they still have to pay child support. But there are few of these cases (less than 10 percent).

Myth No. 7: All civilized countries ban foreign adoptions.

Simply banning foreign adoptions will not make Russia any more "civilized" in this respect as long as its orphanages remain overcrowded and largely substandard. (Notably, the U.S. allows foreign adoptions. Does this make it "uncivilized?")

There are a few Western nations that ban foreign adoptions, but they can afford to do so because they have a modern social and health care infrastructure to support adoptions, their orphanages provide quality care, and there is a long line of parents who want to adopt their countries' own children. None of this can be said of Russia.

Myth No. 8: Russia was a favorite destination for U.S. parents because Americans wanted to "purchase" white, blond and blue-eyed children.

Over the past few years, China was the top country for U.S. foreign adoptions, followed by Ethiopia.

Myth No. 9: Russia's ban on U.S. adoptions was not in retaliation for the U.S. Magnitsky Act.

After Congress passed the Magnitsky Act on Dec. 6, the State Duma proposed symmetrical measures: sanctions against "anti-Russian" U.S. judges and officials associated with torture at Guantanamo Bay. But the Kremlin quickly realized that its retaliatory measures came up short. It was at that point that Russia pulled out all its guns and resorted to an asymmetrical measure: banning U.S. adoptions. The adoption-ban bill was rushed through both chambers of parliament in record time and was included as a central component of Russia's "anti-Magnitsky act."

Myth No. 10: Russia needs to ban U.S. adoptions because U.S. parents and the adoption agencies they hire are corrupt and engage in child trafficking.

Most of the corruption in foreign adoptions is on the Russian side. There were many examples of Russian orphanages that falsified medical records and concealed illnesses to better "sell" children to U.S. parents, who had paid more than $50,000 to adopt.

In a bizarre twist, the case of Dima Yakovlev, in whose honor Russia's anti-Magnitsky act was named, was neck-deep in Russian corruption. Once the Russian orphanage realized that U.S. parents were interested in adopting Dima, it denied members of his immediate family the right to adopt him. One of Dima's grandmothers said the orphanage forged her signature to make it look as if she had refused the right to adopt Dima. His other grandmother said she was threatened by orphanage officials that if she tried to adopt Dima, she would lose her custodial rights to Dima's sister, whom the grandmother had already adopted several years earlier.

Another related Russian myth is that U.S. psychopaths, pedophiles and sadists like to travel to Russia to adopt children because Russian authorities have little ability to check their backgrounds. But U.S. parents are subject to the same strict psychological examinations and criminal background checks from U.S. authorities before they are granted approval to adopt, regardless of whether the child is from Russia or the U.S.

In the end, the Kremlin's massive propaganda campaign against U.S. adoptions, conducted mostly on state-controlled television, was a big success. Unfortunately, the Kremlin showed that if you repeat lies about U.S. adoptions often enough, many Russians ?€” 76 percent, according to a January VTsIOm poll ?€” will accept them as truth.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.