Samuel Raphael Friedman was an American dreamer. In 1932 he moved to the U.S.S.R. to build the nascent communist state, but during the Cold War, his journey ended in execution as a foreign spy.

Friedman is the first American memorialized with a plaque posted outside his former home by the Last Address volunteer project, set up by volunteers to commemorate the victims of Soviet repression.

Born in 1910 to a family of Jewish immigrants, Samuel grew up in working-class Philadelphia. A promising student, Friedman earned general teaching credentials in English, literature, and biology from the University of California at Berkeley in 1931. He learned some politics as well.

“According to his brothers, my father was ‘pink’,” Friedman’s son Timothy told The Moscow Times. “Not red like John Reed, but ‘reddish.’ My father was carrying left-leaning views. Probably from Berkeley.”

A young man on the move, Friedman lived in England for a year and a half before arriving in Russia in 1932.

“The Americans came to Russia during the Soviet Union in order to take part in the building of dreams, in the greatest sense,” said Last Address co-founder Sergei Parkhomenko. “Few people remember now that various factories and whole cities were built by American engineers.”

The Berkeley-educated Friedman worked underground in Moscow on the Elektrozavodskaya metro station for a year. Later in life, he would point out the jack-hammer carved into the station’s friezes and tell his son Timothy proudly, “I worked with that.”

In 1936, Friedman met Polina Rose, another adventurous American of eastern European Jewish descent and his senior by 12 years. Both Samuel and Polina worked as translator-writers for the Moscow News, an English language newspaper.

“She was a pretty independent-minded American woman at first,” according to her son Timothy. “She somehow converted into homo sovieticus. Believing that the people who are in power know better. What moved her to the left, I don’t really know.”

Their first son Paul was born the next year, followed by Timothy two years later. The young family moved into a building on Samotechnaya Ulitsa, newly constructed for the Journal and News Association employees.

As dedicated as Friedman was to the Soviet project, however, he ran into ethnic prejudice and xenophobia. Although he passed the entrance exams at the Moscow Medical Institute, he was refused admission as an alien.

This “glass ceiling” worsened during World War II. He was not allowed to enlist in the Red Army despite its dire need for translators. Moreover, he was separated from his family and exiled to Perm during the German army’s onslaught—foreigners were not entrusted to remain in the capital.

Suspicions lessened by 1944, and Friedman returned to his work at The Moscow News newspaper and the Moscow radio. He even took Soviet citizenship.

But the dangers of xenophobia remained. In 1948, the NKVD was gathering damning material on members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), ostensibly as an espionage ring.

Friedman’s fatal mistake was to invite Gordon Wright, an acquaintance visiting from Britain, for dinner in his communal apartment. Though legal, the invitation was terribly indiscreet, especially for an American family of Jewish origin. At the beginning of the Cold War, any private connection with a foreigner was suspect. Even worse, Wright was in Russia with a diplomatic mission. The couple argued about it, and Polina chose to stay at work that night. It probably saved her life.

Friedman’s case file illustrates how the NKVD tried to use him to connect the JAC with espionage, although the unwitting American had no connections with the organization whatsoever.

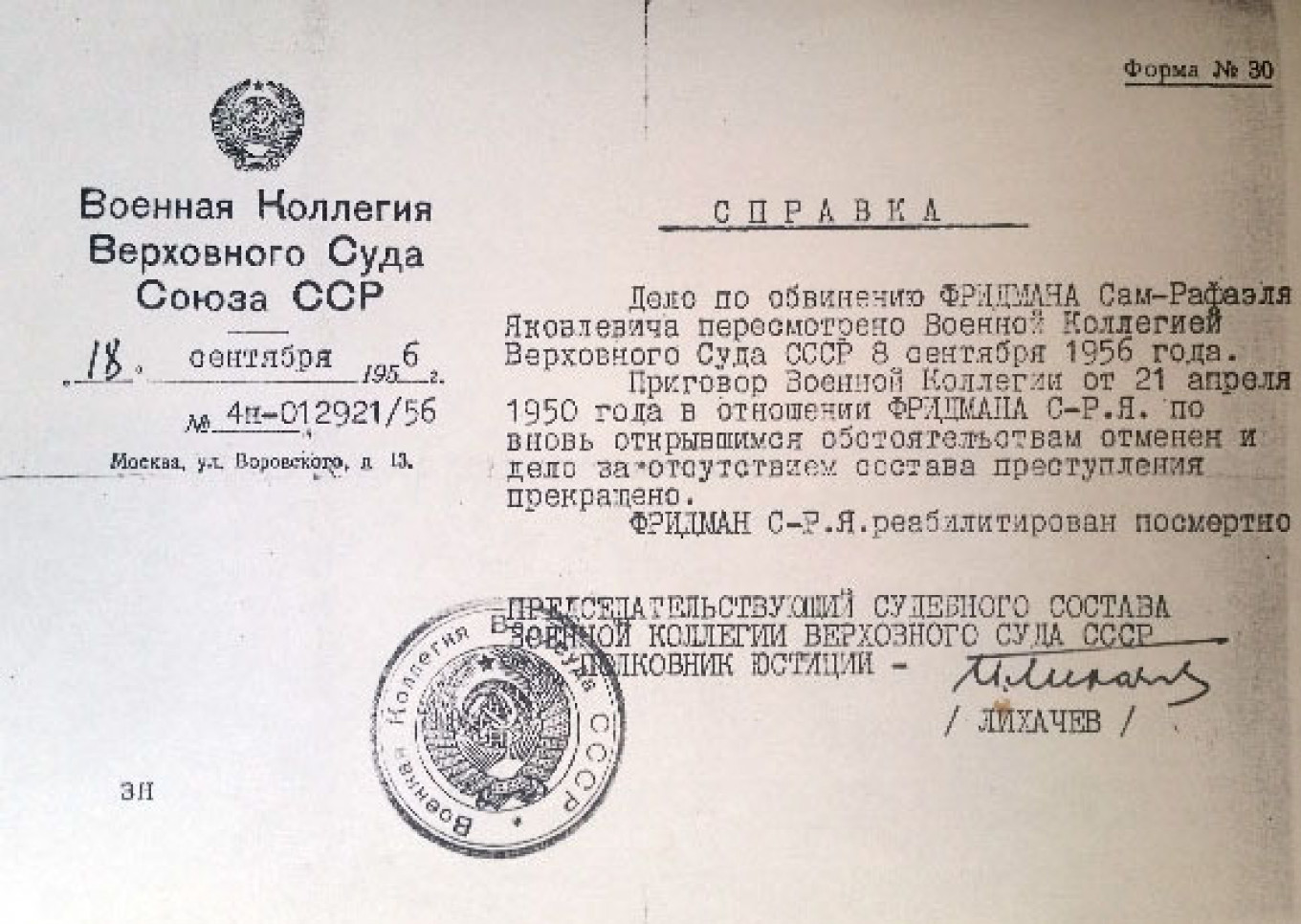

They charged Friedman (called “Sam-Rafael Yakovlevich” in the trial documents) with espionage. He was executed in 1950 after a 13-month sojourn in the bowels of the NKVD. Polina was arrested the following year and sent to a work-camp near Irkutsk. Her boys grew up in orphanages.

After Stalin’s death, Friedman and many others were rehabilitated with the stroke of a pen. Polina arrived in Moscow in time to see Timothy’s High School graduation, and by the 1960s, the family regained a sense of normalcy. Eventually, both brothers emigrated to the U.S. Timothy never found his father’s body.

In 2014, the Last Address project began memorializing ordinary people caught up in the repressions with stainless-steel plaques posted on the sites of their last residence. Modeled on Europe’s Stolpersteine project, which commemorates the victims of Nazism, Last Address plaques function like gravestones, but also warnings for contemporary citizens.

“Although this ‘moral court’ will never have a legal basis,” Parkhomenko said at Friedman’s ceremony, “this is necessary for the next generation. Without it, the country will not develop.”

Family members like Timothy Friedman or residents who live in those buildings can post the simple post-card-sized plaque as long as the residents and owners of the building agree. Timothy applied for a plaque six months ago, but the application was delayed by the difficulty of locating the building’s official residents, many now elderly and living in different locations.

“When I learned about the project,” Timothy told us, “it sounded like a natural thing to do.”