Seseg Jigjitova, a Berlin-based illustrator from the Siberian republic of Buryatia, has emerged as a prominent critic of Russian colonialism and advocate for the rights of Buryats amid Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Buryatia, which shares a border of over 1,000 kilometers with Mongolia, has a population of just over 970,000, with 32% of residents identifying as ethnic Buryats, a Mongolic ethnic group indigenous to the region.

A mountainous region rich in natural resources, Buryatia also covers 60% of the shoreline of Lake Baikal. The world’s largest freshwater lake, Baikal holds a sacred value for Indigenous communities living on its shores, including Buryats, but is now under threat from developers and business interests.

Colonized by Russia in the 17th century, Buryats have grappled with preserving their native language and Buddhist religious traditions amid Moscow’s ongoing russification attempts.

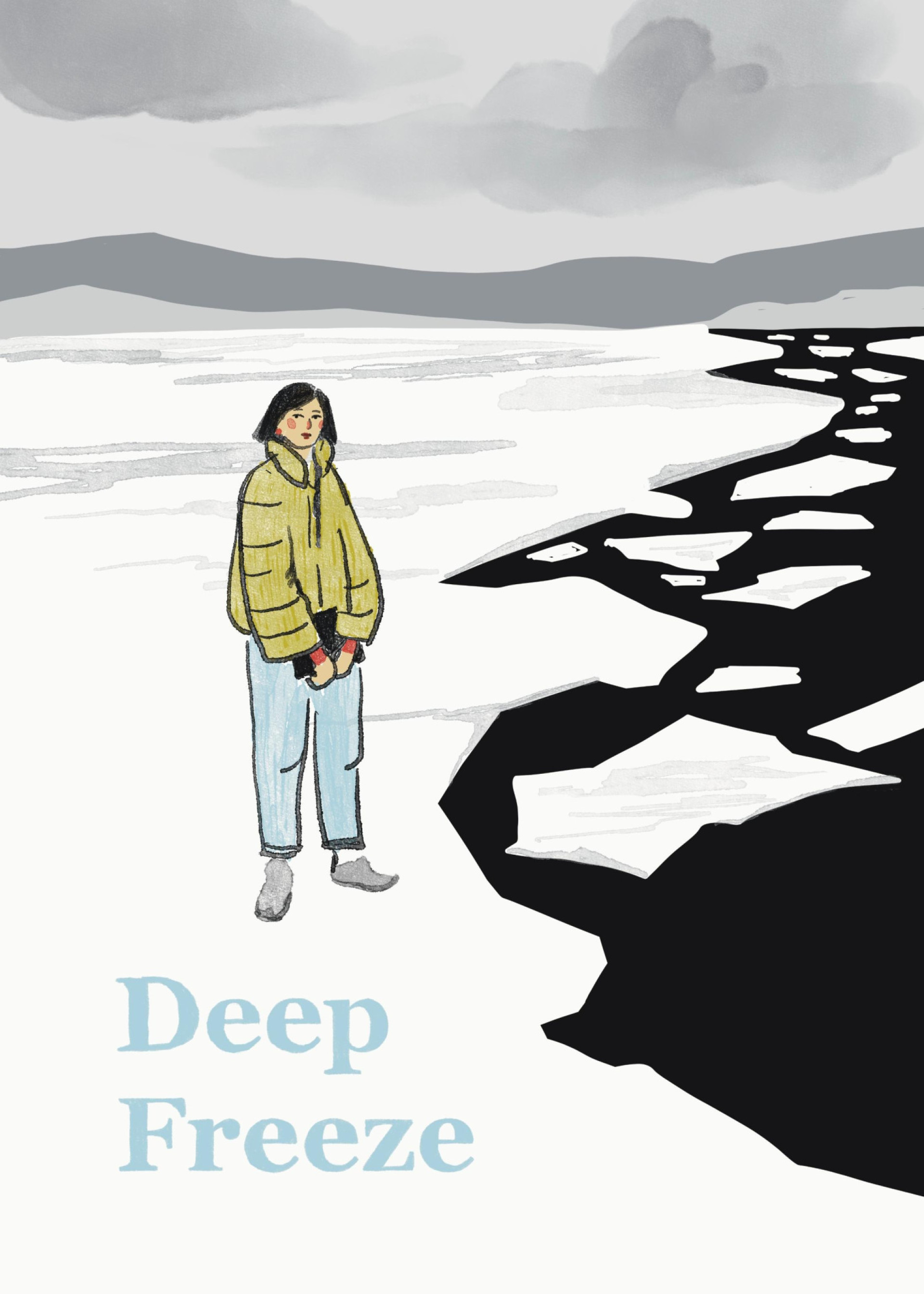

Jigjitova explores the historic impact of Russian colonialism on Buryatia and its peoples — as well as its effects on her own family — in her upcoming graphic novel “Deep Freeze.”

The Moscow Times spoke with Jigjitova about her activism, vocal criticism of the Russian opposition and upcoming book:

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MT: You are an architect by trade who now works as a freelance illustrator, but how did you become an activist?

SJ: Becoming an activist was not entirely my choice. I’m not a public person, and public speaking puts me far outside my comfort zone. But the beginning of Russia’s invasion [of Ukraine] changed everything.

I felt that every single Buryat voice against the invasion mattered. Many people know about the disproportional mobilization and higher per-capita death toll among the Buryats compared to ethnic Russians. But very few know of thousands of Buryats who left Russia to boycott the mobilization and of the many Buryat activists opposing the war.

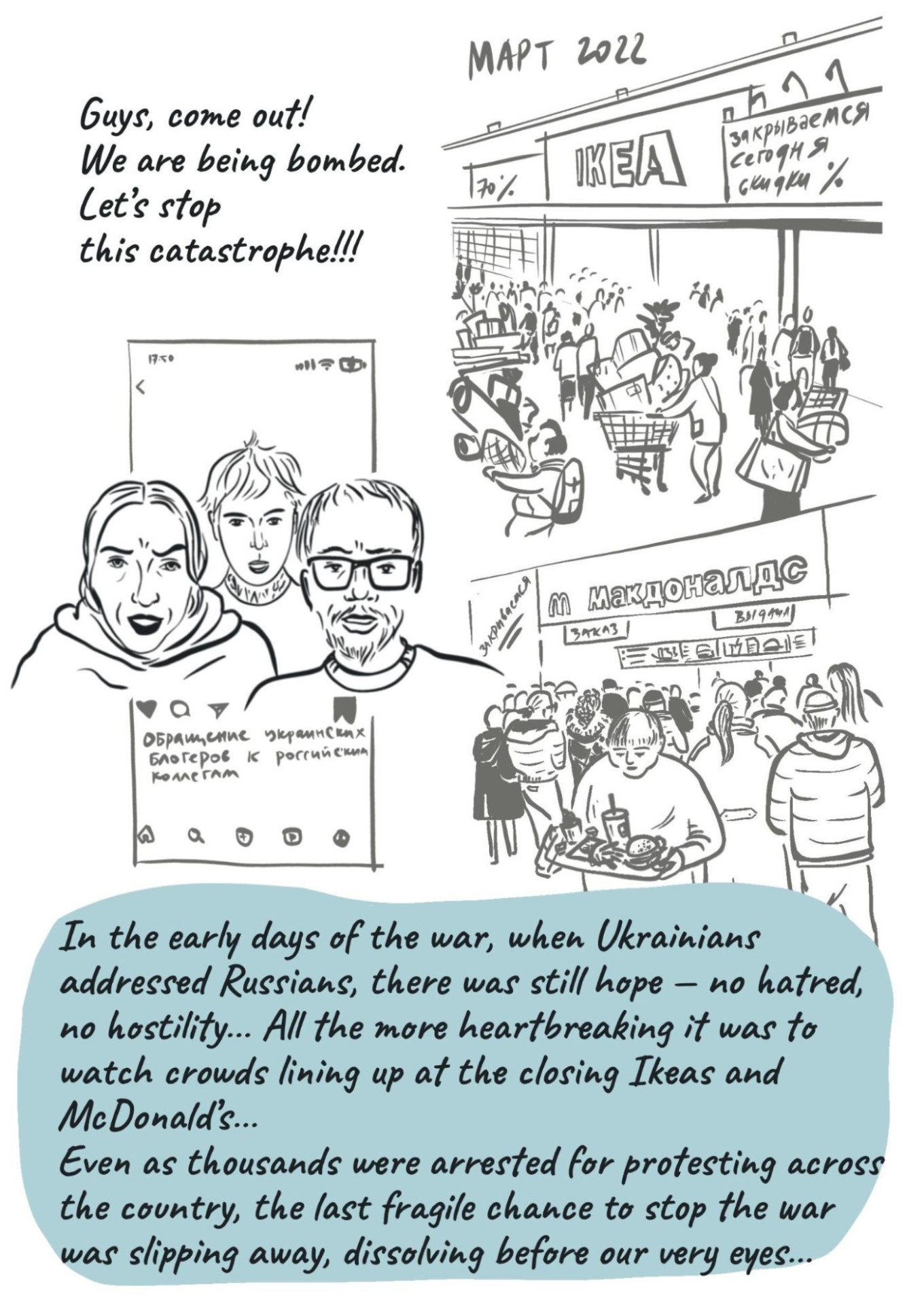

With the large-scale war in Ukraine came the uncomfortable realization that Russia hasn’t changed. It hasn’t rethought its colonial and racist legacy, nor has it parted with the ideology of the Soviet era or that of Russian supremacy.

MT: Could you tell us a bit about your upcoming book? Is this project an extension of your activist work?

My illustrated book, which will first be published in Russian, is a search for answers.

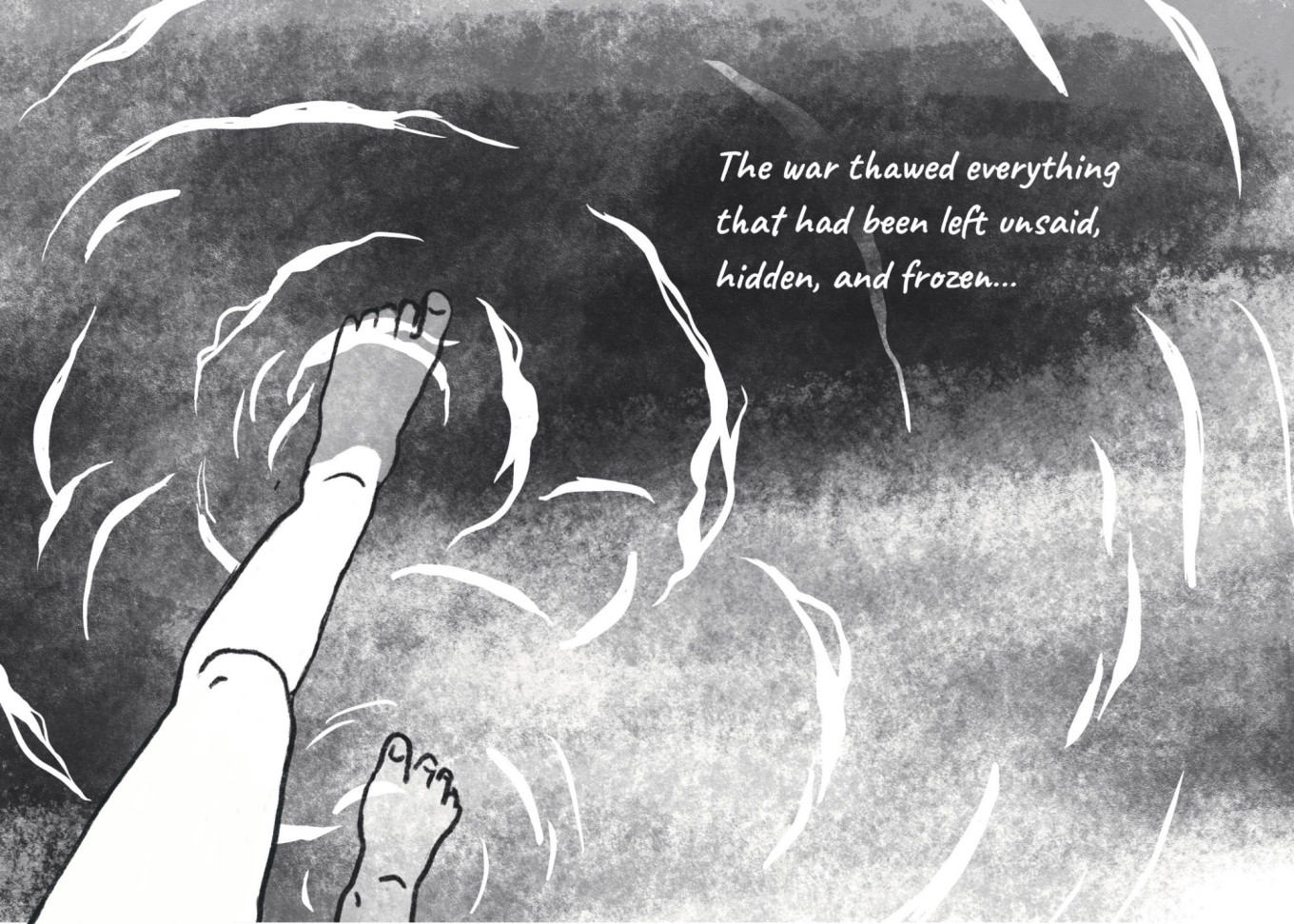

Back when I was a student in Irkutsk in the 1990s, I had many questions that I couldn’t find answers to. These questions, which had been frozen for a long time, began to resurface with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and with them came complex answers.

The illustrated book includes autobiographical episodes, family ethnography and reflections on tragic [historic] events that affected every Buryat family but were never discussed.

Since Soviet times — and now even more so — the version of Russia’s history taught at schools and universities has focused exclusively on ethnic Russians, their conquests, their culture.

Fortunately, many activists, historians and journalists from Buryatia — even those still in Russia — are now revisiting the erased pages of history. They are rethinking the republic’s history and reclaiming the narratives from which they were excluded.

Young Buryats — many of whom didn’t grow up speaking their native language — are learning the Buryat language. Even some Russians in Buryatia have started learning Buryat. This is great!

MT: You are a vocal critic of the Russian opposition. Over the past few years in activism, have you found any allies among the Russians? Or do you think Indigenous activists are destined to fight for their rights alone?

SJ: We have allies among some Russian civil rights activists, among people in the countries that were subjected to Russian colonization and even among some Ukrainians, who often understand our struggles better than Russians do.

The Russian opposition — with which I initially identified — has not been able to think critically [about historic and present events] and, more importantly, has not been capable of self-criticism. Many members of the Russian opposition, the so-called Moscow intelligentsia, have long lived in a parallel reality detached from the rest of Russia. It seems that they have drifted even further away from reality since 2022.

We hear many calls for unification [with the Russian opposition], but I think we need to reconsider the idea of unity when applying it to the Russian Federation. There never was any real unity within Russia beyond the concept of the ‘friendship of peoples’ pushed onto us by propaganda and ‘unity’ through forced russification [of non-ethnic Russians].

I often ask myself whether unity within Russia — or any kind of internal civil truce or alliance — is possible at all without a clear and honest recognition of historical wrongdoings by Russia and its predecessor states, without it taking ownership of a difficult legacy, and without justice [for Indigenous people].

To achieve unity, we need to recognize Russia’s colonial violence and take both collective and personal responsibility for having done too little to prevent the war in Ukraine. We must also recognize that the conviction that the Russian identity is superior over all others, the great Russian chauvinism, played a key role in shaping imperial policies and was one of the reasons for today’s war. Putin is a symptom of this, not the cause.

MT: You have lived in Germany for 20 years. What has been your experience with trying to explain the plight of non-ethnic Russian citizens in Russia to Europeans?

SJ: Most people imagine Siberia as the North Pole with dog sleds roaming around, though I’ve never seen a single dog sled in my life. In reality, Siberia is a vast region inhabited by different peoples who speak Turkic and Mongolic languages and have diverse religious beliefs and cultures.

Siberia remains a huge blank spot not only in the minds of Europeans but also of the Muscovites.

Unfortunately, some German media unintentionally support Moscow-centrism and suffer from so-called Berührungsängste (German for the “fear of contact with sensitive topics”). They amplify voices like that of Vladimir Milov, who claims there was no violent russification in Russia, or Vladimir Kara-Murza, who recently made some shocking remarks when speaking at the French Senate.

But things are changing slowly. Some educational departments in Germany are revising their curricula on Russia to make them less cliché-ridden and move away from the view of Russia as just a country of ethnic Russians.

MT: Do you ever dream of returning to Buryatia? What kind of republic would you want to return to?

SJ: The only thing I can say for sure about the future is that we have hope.

I envision a republic of Buryatia where all people, regardless of ethnicity, are free. A republic where people know how to exercise their fundamental rights, understand and respect its difficult history and live free from Moscow’s exploitative grip. A republic whose fate is determined solely by its people.

I believe the process of gradual decolonization has started. As activist Viktoria Maladaeva said recently, “Many people are now waking up from a colonial sleep.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.