“This is the FBI, your parents are from Siberia.”

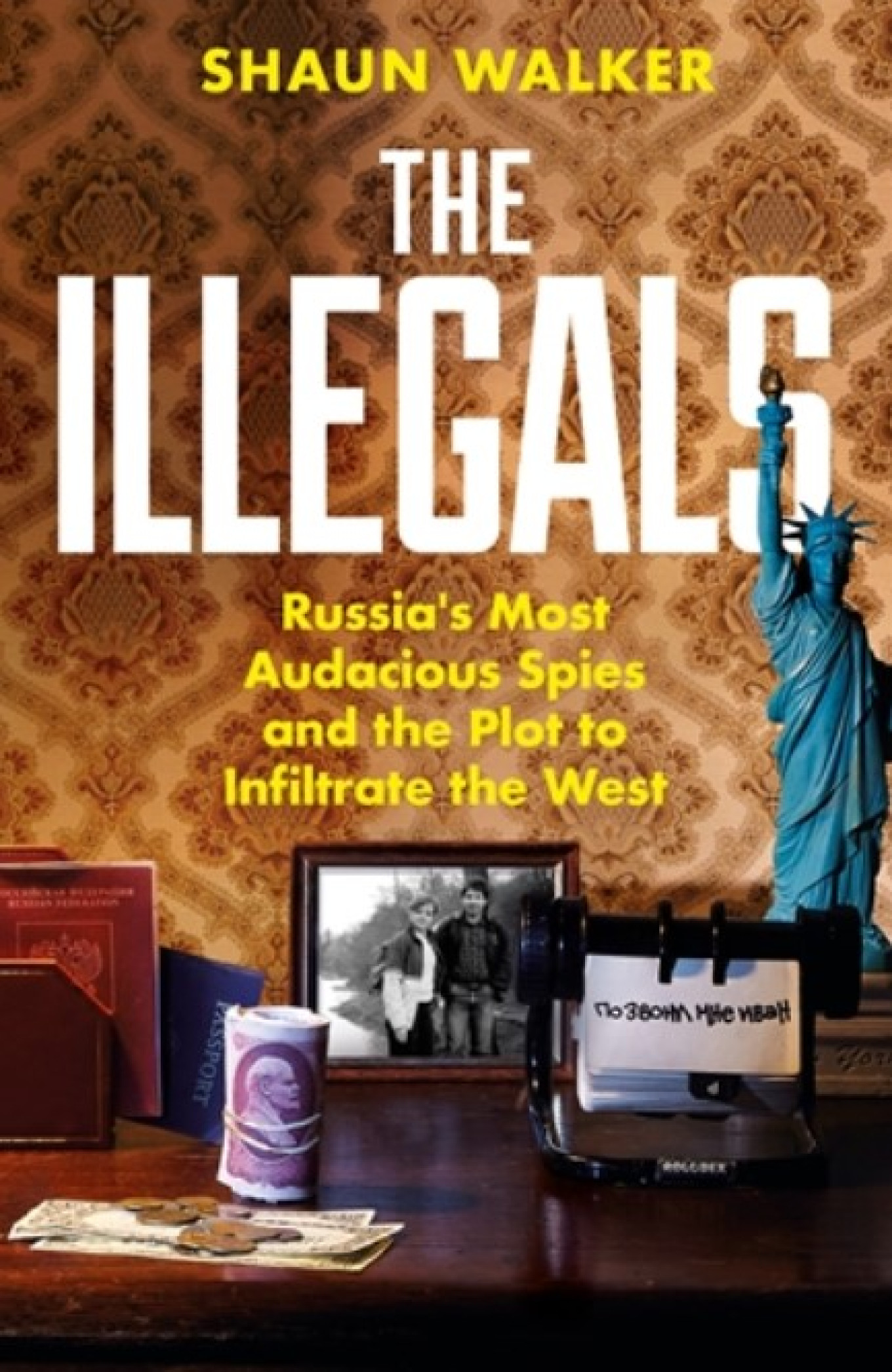

“I just thought it was a really wild family story,” Shaun Walker told The Moscow Times, describing the arrests that inspired his sweeping study of Russia’s deep-cover spy program, “The Illegals.”

Back in 2010, the ordinary “Canadian” couple Andrei and Elena Bezrukov were exposed as Russian sleeper agents and were sent back to Moscow in a spy swap. The couple’s teenage sons had no idea they were Russians, and eventually sued the Canadian government to get their passports back.

“Imagine that, it’s your twentieth birthday, the FBI come knocking, they arrest your parents, and it turns out they’re from Siberia.” “Operation Ghost Stories” was the result of years of counter-surveillance by the U.S., who had a double-agent in the Russian program.

Journalist and author Walker was working for The Independent in Moscow at the time, but lost out on the chance to interview the family, who were “whisked around in buses” following their unceremonious return.

That missed encounter later became a 10-year odyssey to track down the survivors and descendants of Russia’s notorious illegals program, which ran from the Bolshevik era to the present day and is still active. Walker waded through archives, gained the trust of retired illegals, and pieced together stories from memoirs.

The illegals program was run by Directorate S of the KGB and later by the SVR, the foreign branch of modern Russia’s intelligence bureau. Promising young recruits were grilled for ideological suitability before embarking on years of training in languages and behavior. They were then sent out to live under the identities of dead or living foreigners with false passports — sometimes forever. Later spies worked in pairs, meaning that their lifetime romantic partners were chosen by the KGB.

Walker sets the stage for a rotating cast of characters whose lives span the duration of the Soviet Union and its aftermath. The early illegals, known as the “greats,” carried out risky undercover missions in the West — such as a cabaret act whistler who was plucked from his stage role to impersonate a Nazi. There was also an attempt to kill the Yugoslav autocrat Tito, involving a poisoned jewelry box and a spy who spent many years posing as a Costa Rican diplomat.

“STALIN, stop sending people to kill me,” wrote Tito, in an angry letter to Moscow. “We’ve already captured five of them, one with a bomb and another with a rifle.”

The “Costa Rican” plot was called off in 1953 due to Stalin’s sudden death, much to the relief of everyone involved.

Walker told The Moscow Times he believed it was easier for these early spies to deal with the strain of secret-keeping because their day jobs were “cool” — diplomats, or aristocrats operating in elite Western circles. In later years, Directorate S often issued spies with mundane identities as students, IT workers, or housewives.

“That kind of disconnect doesn’t sit well with most people’s egos,” he explained, “Most people need validation from their surroundings, and you’re presenting to 99% of the people you meet as someone boring, or really random. It takes an odd type of personality to enjoy these micro-deceptions.”

Although “The Illegals” is an entertaining book, Walker makes it clear that the program caused lasting psychological harm — to the victims of spies, to the spies themselves, and in particular, to their families. Several spies in the book considered suicide, and Walker told The Moscow Times that at least one of the retirees he spoke to had suffered emotionally from the strain of her double life.

While London’s Met police recently faced a reckoning for the “spy-cops scandal” where undercover police fathered children with their unknowing surveillance targets, Walker believes that a similar movement in Russia is a long way off and will most likely never happen. Putin’s Russia treats returning illegals as patriots who made the ultimate sacrifice.

“There is some sympathy,” he acknowledges, referencing the most recent spy swap. In an echo of Operation Ghost Stories, two of the Russians exchanged for the group of Western political prisoners were the children of a spy couple who learned that their parents were spies for the first time.

The Spanish-speaking boy and girl believed themselves to be Brazilians living in Slovenia (it is typical for Russia to give its spies foreign identities in a target country to reduce the risk of slip-ups). Walker told The Moscow Times that during the negotiating period the children lived with a Slovenian foster family and continued to attend an international school. Their parents were in jail, awaiting their plane back to Moscow.

“The foster family and even the [Slovenian] officials wanted the kids left out of it completely. ‘Please don’t go after the kids, they don’t know anything, they don’t deserve it’,” Walker explained. Yet the minors were included in the swap, and were greeted by Putin in the airport with a hearty “Buenos noches!”

“It’s treated as this jokey thing, rather than as a traumatic experience for an 11-year old.”

Some of the former spies in "The Illegals" are telling their stories for the first time. Walker tracked down “Peter,” who was the subject of a rare attempt to create a “second-generation illegal” in the 1970s when his father let him in on his real identity and sent him to Moscow for training. Peter later opted for a quiet life in witness protection, where Walker persuaded him to meet for coffee after his home address was inexplicably published in a news article.

Peter didn’t want to talk. “He said — absolutely not — so it was really a gradual process of warming him up. By the end [of the interview process] I got him to a point where he said ‘actually, this has been useful, and it’s about time,” Walker told said.

Not all of the illegals were welcomed back with open arms. Yuri and Tamara Linov worked on assignment in several countries, often leaving their young children behind, and struggled to produce the kind of material their handlers wanted. Yuri, a brilliant linguist, spent years as a bathmat salesman in Dublin. The Irish “regaled him with their life stories for hours on end” but had no useful intel for the KGB.

Yuri’s wilderness years in Ireland and his eventual capture by Israel didn’t fit with Putin’s heroic narrative, and the couple retired into poverty.

Deep cover was not always needed in the '90s and early 2000s, when business people and “socialite spies” like Anna Chapman were able to get close to Westerners without suspicion or the need for a false passport. Russia’s war in Ukraine has changed that.

An ongoing debate rages over whether the huge effort involved in creating illegals is worthwhile in the digital age. Walker acknowledged that inventing “a whole person” — a German, or a Brazilian — is getting harder, but believes we may see a revival of old-school deep-cover operations as a result of anti-Russian sentiment driven by the war.

With a masterful eye for detail, Walker illuminates tradecraft previously unknown to the West, and humanizes the men, women and children caught up in Russia’s spy program. The artificial lives of the illegals provoke us to question what is true and false in our own lives — in a twist worthy of a novel, some of the spies prefer their assumed identities to their real ones, and choose to carry them forever.

It’s a tremendous piece of journalism.

The Illegals: Russia's Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West

Chapter 8

The Whistler: Undercover in Nazi Germany

A Russian and a German Communist are trained to impersonate Nazis and dropped behind enemy lines to coordinate the assassination of the Nazi governor of Belarus.

Once Nikolai and Karl had eased into life in occupied Minsk, they needed to seek out the contacts who could help them carry out their mission. They approached Elena Mazanik, a housekeeper at Kube’s mansion in the center of the city. Kube lived there with his wife, Anita, an actress he had wooed after she appeared in one of his plays, and their children. Elena had worked in a government cafeteria before the outbreak of war and had also been informally employed as an NKVD informer. Her husband had worked as a driver for the NKVD, andwhen the war broke out, he fled, leaving Elena trapped in Minsk. She found employment at the officers’ casino that Nikolai and Karl had visited, first as a cleaner and then as a waitress. Before he became worried over the threats on his life, Kube frequently visited the casino, to grill pretty female staff about their backgrounds and political views.

The women he liked the most received offers to work as housekeepers at his villa. Elena, at twenty-seven, was too old for Kube’s tastes, but she became friendly with Karl Wildenstein, a Nazi officer who served as Kube’s right hand, and Wildenstein took a shine to her. Later, back in Moscow, interrogators would ask Elena many times if her relationship with Wildenstein had been sexual. He gave her money and vodka and flirted with her, she admitted, but insisted it never went any further.

Whatever the truth, Wildenstein asked Elena to work for him as a maid, at his small suite of rooms on the second floor of the newly built governor’s mansion. A courier from Kutsin’s partisan encampment relayed information to Nikolai that Elena’s husband was alive and well, working as a driver for the NKVD deep in Siberia. The NKVD surmised that Elena was probably not an ideological Nazi, but someone who was trying to get on as best as possible under the regime of the day. As such, she could be amenable to pressure. Nikolai had one of his contacts whisper to Elena that a man had come from Moscow with information about her husband, and entice her to a meeting. When she arrived, Nikolai relayed greetings from her husband, promising that he was “alive, and in good health.” Then Nikolai told her he had arrived in Minsk on an important mission and needed her help, appealing to her Soviet patriotism and darkly hinting that it was time she proved her allegiances.

“Our country still trusts you. But there is a limit. For a long time, you have refused to face the truth. Now you’ll have to,” said Nikolai. “I am not threatening you, merely reminding you about certain unfortunate circumstances,” he added. Having made his point several times, he paused, seeing that Elena’s fingers were clasped to the edge of the table and her face had drained of color.

“Don’t give me your answer at once,” said Nikolai. “Especially because in your position there can be only one answer. We will not accept another.” With that, he left.

Elena’s reluctance to agree to help was not out of loyalty to her German bosses. In fact, she had already been approached by one of the other groups targeting Kube. As one of the few people in Minsk with direct access to the Reichskommissar, she was in high demand.

The other group had passed on a vial of poison to her, in the hope she might slip it into the Nazi’s food. The problem was that Kube’s children tended to eat earlier in the evening, meaning that if she put the poison into the soup pot during the day, the alarm would be raised before Kube and his wife ate. The plan was eventually discarded. Now an unknown man in a Nazi uniform had appeared, and Elena was wary of his manner. She worried Nikolai could be a member of the Gestapo sent to test her. Her nerves were steadied when a friend of hers, a cook who had expressed willingness to join the resistance, was enlisted by Nikolai’s contacts to vouch for him.

A week later, Nikolai met Elena again, dressed in full German uniform and with a bright pink package under his arm, wrapped as if it were a gift for a lover. Inside were two small magnetic bombs, with pencil detonators and printed instructions. Elena received Nikolai warily, sitting on a stool with hands folded and waiting to hear what he had to say. He revealed the reason for his journey to Minsk. “In your hands is a rare opportunity to help in a mission that will have a place in the history of the war,” he told her. She protested that she would have nothing to do with such folly, but heard Nikolai out. He told her there were two options: She could give him precise information about Kube’s movements, and assist in getting him and others into the grounds of Kube’s villa, where they would ambush him with a grenade. There was also the second plan.

“There is a little contraption called a magnetic bomb. A small, inconspicuous box, which clamps tenaciously to any object made of iron, even to the springs of the gauleiter’s bed,” he said. He explained how the pencil detonator could be set so as to program the bomb to go off at a particular time.

“I don’t know, Comrade,” said Elena, and with her use of that final word Nikolai was sure she had made up her mind. He bade her fare-well and left her the gift-wrapped package with the bomb.

On September 21, Elena rose at six thirty. After pacing around her apartment and running through all eventualities in her head over and over, she placed the bomb in her handbag and walked to work. She also took with her the unused vial of poison, resolving to swallow it if captured. When she arrived at the mansion, she made her way upstairs. She was only permitted to be on the second floor, which housed Wildenstein’s suite as well as Kube’s office and guest bedrooms. Kube’s bedroom and the dining area on the first floor were strictly out of bounds.

Elena began cleaning Kube’s quarters, emptying the ashtrays and removing the whiskey glasses left from the previous night. Both Wildenstein and Kube headed out. Elena nodded hello to Anita and said she had toothache, asking permission to visit the dentist later in the day should it get worse. Shortly after, Anita went out to run some errands, taking one of the servants with her. This left just Elena and one other young servant, Yanina, in the house. Elena knew Yanina had a secret German lover, so she beckoned her over and whispered that because the house was empty, Yanina could sneak up to the second floor and call him from the telephone in Kube’s office. The girl accepted the offer gleefully and bounded up the stairs.

Elena picked up her handbag and a pair of children’s trousers and crept down to the first floor. If discovered, she planned to say she was searching for thread to mend the pants. With her heartbeat sounding in her ears as loudly as a drum, she removed the bomb from her bag, lay on the floor next to the bed, and affixed it to the underside of the mattress. She twisted the pencil detonator to fifteen hours so that it would go off in the middle of the night. She then sat on the bed and gently bounced, to make sure the bomb would not fall. It was a nervous moment, but the device remained in place. Gathering up her bag and the trousers, Elena hurried back out of the room and, seeing Yanina approaching, told her the toothache had become worse and she was going to the dentist immediately.

When she returned home, Elena grabbed her sister Valya, and the pair of them hurried to an agreed pickup point, where a driver with a permit to travel outside Minsk was waiting for them. The sisters jumped into the cargo section of the driver’s truck and were tossed around for half an hour until it ground to a halt a dozen miles outside Minsk. They jumped out and made their way through the woods to a partisan encampment. At two in the morning, as Kube lay fast asleep in bed with his wife, and Elena and her sister paced nervously at the camp, the bomb detonated as planned. Kube was killed instantly; his wife miraculously survived.

Karl and Nikolai were awoken early in the morning by the son of the cook who had vouched for them to Elena. His cheeks were blazing red, and he spoke in rapid adrenaline-fueled sentences. Kube was dead, blown to bits in his sleep, he said. The SS were on the hunt for the perpetrators and had blocked all exits from the city. Quickly, Karl and Nikolai donned their uniforms, left the apartment, and flagged down a lorry packed with SS men that was headed for the concentration camp at Trostenets, south of Minsk. The lorry sailed through the army and SS checkpoints on the outskirts of the city, and when it reached a fork in the road, Karl and Nikolai jumped out. Once the vehicle had disappeared into the distance, they left the road and clambered through the forests. That night, they ran into a detachment of partisans, part of a search party sent from the base to look for them.

They peeled off their Nazi uniforms and awaited news of when a plane might arrive to take them back across Soviet lines, their mission an unequivocal success.

The Soviet Union sent fifteen thousand operatives across the lines during the war years, Sudoplatov later estimated, and between them they were responsible for the assassinations of eighty-seven high-ranking Nazis. Many of these operatives were disguised as Germans. Nikolai Kuznetsov, who posed as Oberleutnant Paul Siebert and killed at least six Nazi officials before he was captured and killed, later became one of the most celebrated Soviet war heroes. The assassination of Kube was perhaps the most spectacular hit of all, so much so that inside the SS and Gestapo there were rumors that it must have been an inside job by a competing faction in the Nazi hierarchy.

Excerpted from “The Illegals. Russia's Most Audacious Spies and the Plot to Infiltrate the West,” written by Shaun Walker and published in the U.K. by Profile Books and in the U.S. and Canada by Penguin Random House. Copyright © Shaun Walker 2025. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes removed for ease of reading. For more information about Shaun Walker and his book, see the publishers’ sites here and here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.