Victoria Lomasko’s new book “The Last Soviet Artist” was presented last week in the New York office of her American publisher, n+1. Together with her two previous works, “Forbidden Art” and “Other Russias,” “The Last Soviet Artist” chronicles how Russian society has moved from democracy to dictatorship over the last 13 years.

“The Last Soviet Artist” consists of three parts. The first part, “Traces of Empire,” describes Lomasko’s travels to regions of Russia (Dagestan, Ingushetia), as well as post-Soviet states (Georgia, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan). It reads like a graphic travelogue with a strong sociological component.

Lomasko had originally planned to “travel across the so-called post-Soviet space…mostly working not like a graphic journalist, but a sociologist.” As she writes in the book’s introduction, “I produced my drawings right where the events depicted in them occurred and interviewed people using methods drawn from journalism and sociology.”

“Of course, I understood that when I finished the book, I’d be asked about colonization, about Orientalism, about why I traveled from the center of a former empire. To avoid the path of Russian and Soviet Orientalist artists, I traveled only at the invitation of local feminist groups. I conducted workshops for them on social graphics, and they talked to me about their society and suggested subjects.” Indeed, the book has many more heroines than heroes and deals with the issues of gender rights.

Another important subject is what Lomasko calls “traces of empire.” She explained that these traces are not “only physical heritage,” but also include what the new generation thinks about the Soviet past.

Lomasko’s original plan was to visit all countries in Central Asia, as well as the Baltic states and Ukraine, but the Covid pandemic foiled these plans. Instead, the artist went to Minsk to see how the peaceful protests against the results of the 2020 elections unfolded. That’s where the second part of the book, entitled “The Last Soviet Artist Becomes Someone Else,” begins.

Lomasko said that at that point she believed that if “the majority of citizens took to the street, they would win.” When she went to Belarus, she wanted to depict their victory. Since the borders with Belarus were closed due to Covid, she paid a minibus driver to hide her in a large checkered plastic bag and illegally cross the border. When she arrived in Minsk, she realized that there had been hundreds of arrests and beatings, and some people were missing. “I thought I would depict victory, but I found that it was a defeat,” said Lomasko.

Lomasko said that when the police violently broke up the rally she realized that she wasn’t “just a graphic journalist following the media agenda. No, the situation was much more serious. These were really historic processes, and I must be an artist and a writer and use symbolic language. So I started combining graphic reports with symbolic compositions.”

Lomasko said that it became clear that “the next collapse would happen in Russia.” The chapter following the Belarus protests is devoted to the aftermath of Alexei Navalny’s arrest upon his return to Moscow after receiving treatment in Germany for Novichok poisoning.

One section of the chapter is about some elderly people unable to get home: public transport was suspended due to the protests and they couldn’t afford a cab. They blame all their problems on the protesters. This became one story in the second part of the book, which is about the conflict between generations: the generation that grew up during the Soviet era, and the newer generations — those in their thirties, twenties, or even younger.

The third part of the book includes two pieces that were published in U.S. media in 2022. “Moscow Under Snow” was commissioned by The Nib, the largest website for documentary and political comic strips. It describes Lomasko’s daily life in Moscow — her neighborhood and the people on the eve of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Another strip is a collaboration with Joe Sacco, one of the best-known graphic journalists in the world and author of the famous graphic novel “Palestine.” “Joe wrote a review of ‘Other Russias,’ and he remembered me and asked if he could buy tickets for me to leave Russia,” Lomasko said. “But I said, ‘Better help me get my voice back. I want to write my stories, but the Western audience isn't ready to listen to me — they're ready to listen to you.’” The resulting piece, called “Collective Shame” was published in The New Yorker.

Through reportage, symbolism, and lived experience, “The Last Soviet Artist” captures a society in transition — and in collapse. Lomasko’s latest work not only documents the end of an era, but asserts the enduring power of art to bear witness, even in exile.

The Last Soviet Artist

Ingush Towers

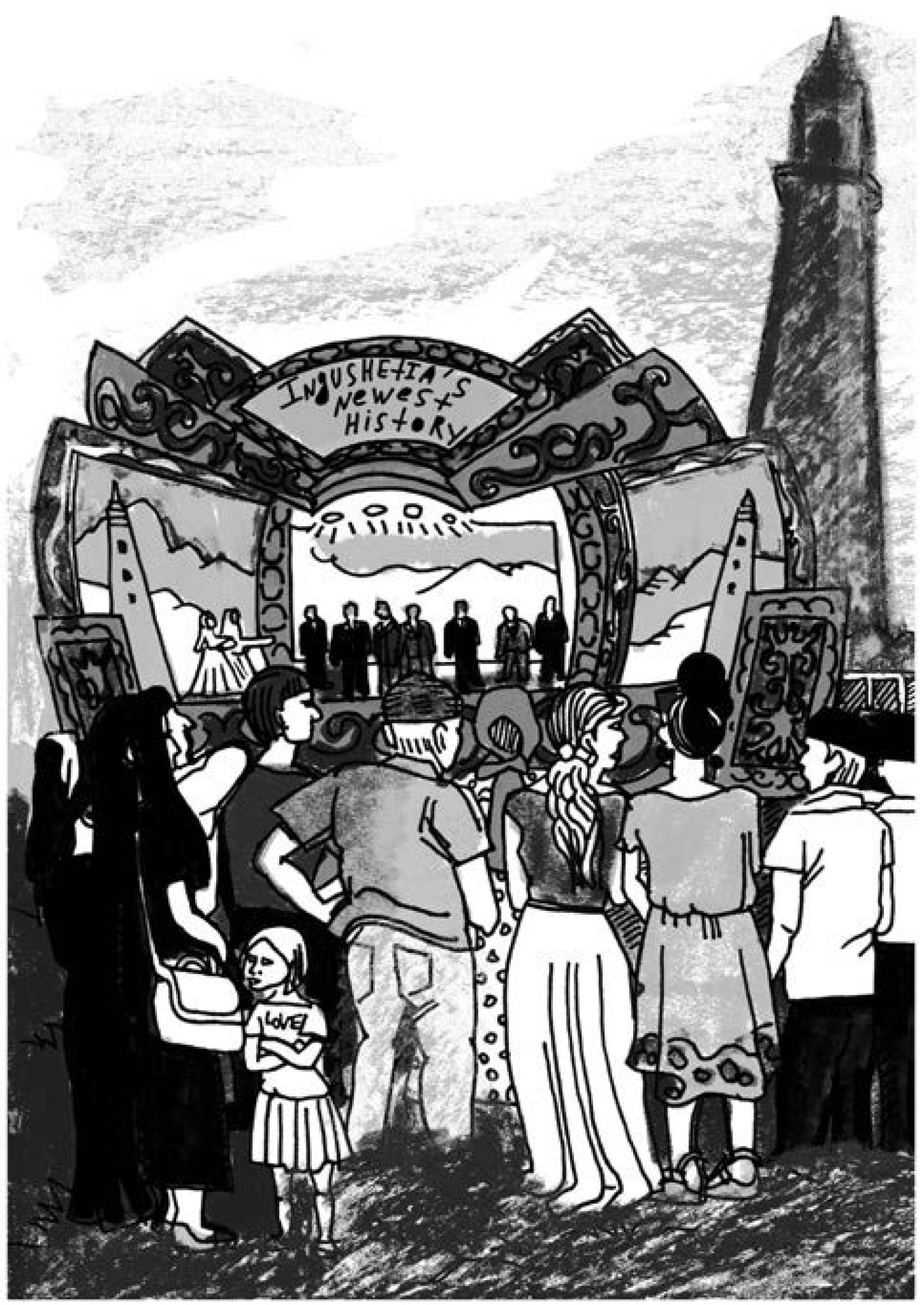

Established in 1994, Magas is the youngest capital city in the Russian Federation. Even the trees haven’t had time to grow in yet. There is a good number of Russians living here alongside the Ingushetians, including FSB agents and their families. There was a large residential complex constructed just for them, with special schools and a daycare.

The city was celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the foundation of the Ingushetian republic during my visit. I saw a stage bedecked with giant screens, and behind the stage there was an awkward-looking tower, a replica of the medieval structures. Behind the tower was a large expanse of empty plain. My trip to Ingushetia depressed me. It felt like I was moving around among hurriedly assembled set decorations in a space that had been scorched of all of its history.

There were some important-looking men declaiming on the stage: “Because of Putin’s heroic efforts, today, Russia — and, by extension, Ingushetia — is developing successfully. All hail the friendship of the nations and the unity of Russia!” If you spoke to regular Ingushetians, you would hear totally different things. “People come after you Russians for your political views. They come after us a priori because of our nationality.”

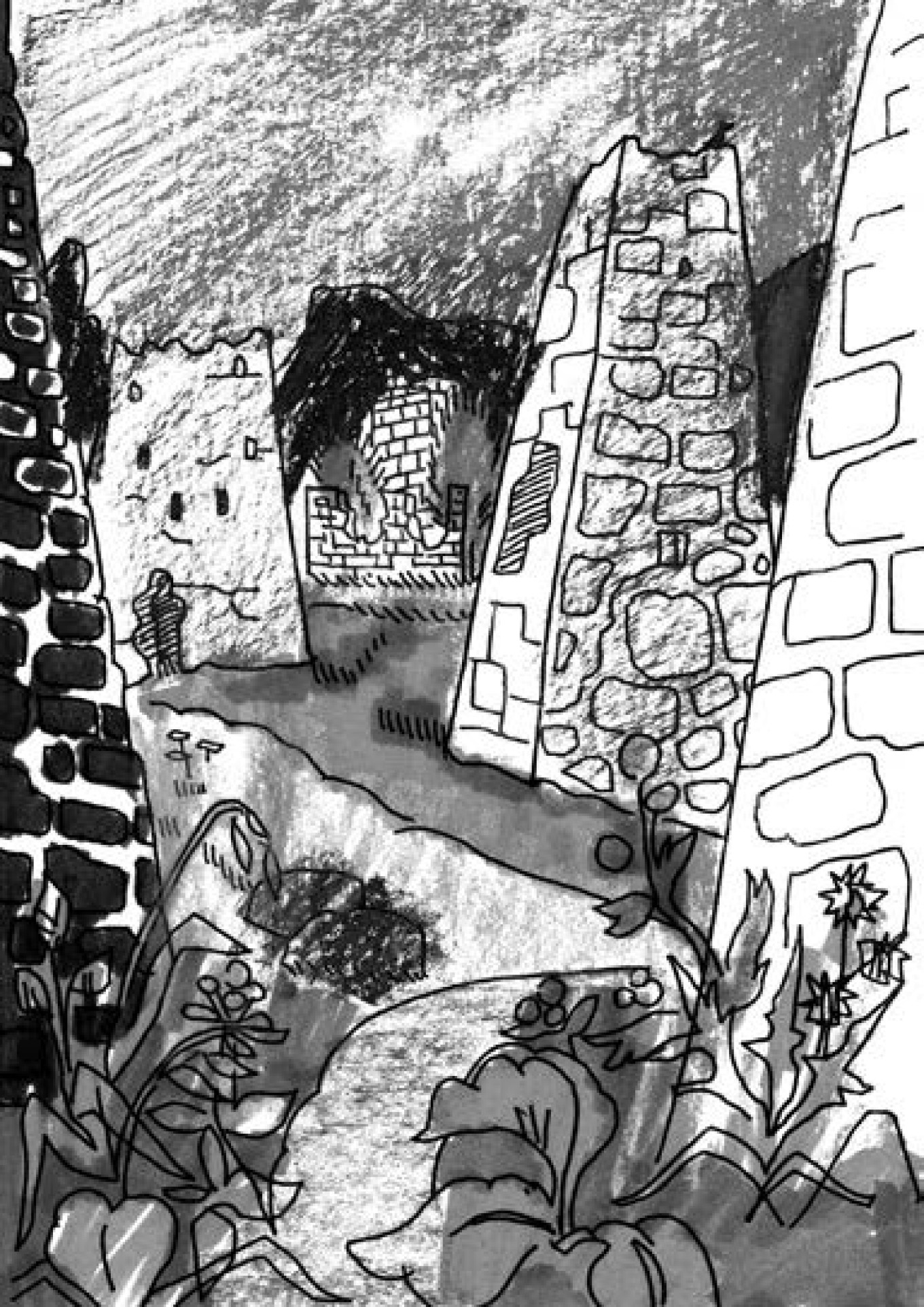

When I shared my impressions with the Ingushetian family I was staying with, they offered to take me out to the mountains to show me the Ingush towers. I knew that the Ingushetians had once been a mountain people, but I didn’t know that the local mountains were full of medieval settlements.

We first passed through Magas with its boring new construction and then through the villages with their red brick houses. Then the hills began, and finally, the mountains. The towers stood on the mountain slopes like pikes stuck into the ground, tips up. Every family was supposed to build their own tower.

We got out of the car and climbed up into the mountains. For this ascent even the daughter of the family had put on pants — she couldn’t be expected to trek up a slope overgrown with wild grasses while wearing a skirt. A friend of the father, a documentary filmmaker, told us about the structures we were taking pictures of: medieval homes and defensive towers, sunny ancient burial grounds and pagan shrines. On the facade of one of the shrines we even found the remains of a bas-relief illustrated with mythical characters.

The director pointed out the holes in the walls of some of the towers and said that these were bullet holes. During the deportation of the Ingushetians, their towers were partially destroyed by Soviet soldiers. “Russia can destroy,” said the father of the family, “but it can never restore.”

We came to the banks of a mountain river, and the men made us shish kebabs. This small group of people was gathering strength among their ancient settlements. Time stopped.

Excerpted from “The Last Soviet Artist” written and illustrated by Victoria Lomasko, translated from the Russian by Bela Shayevich, and published by n+1 Books. Text and images © 2025 Victoria Lomasko. Translation © 2025 Bela Shayevich. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information about Victoria Lomasko and the book, see the publisher’s site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.