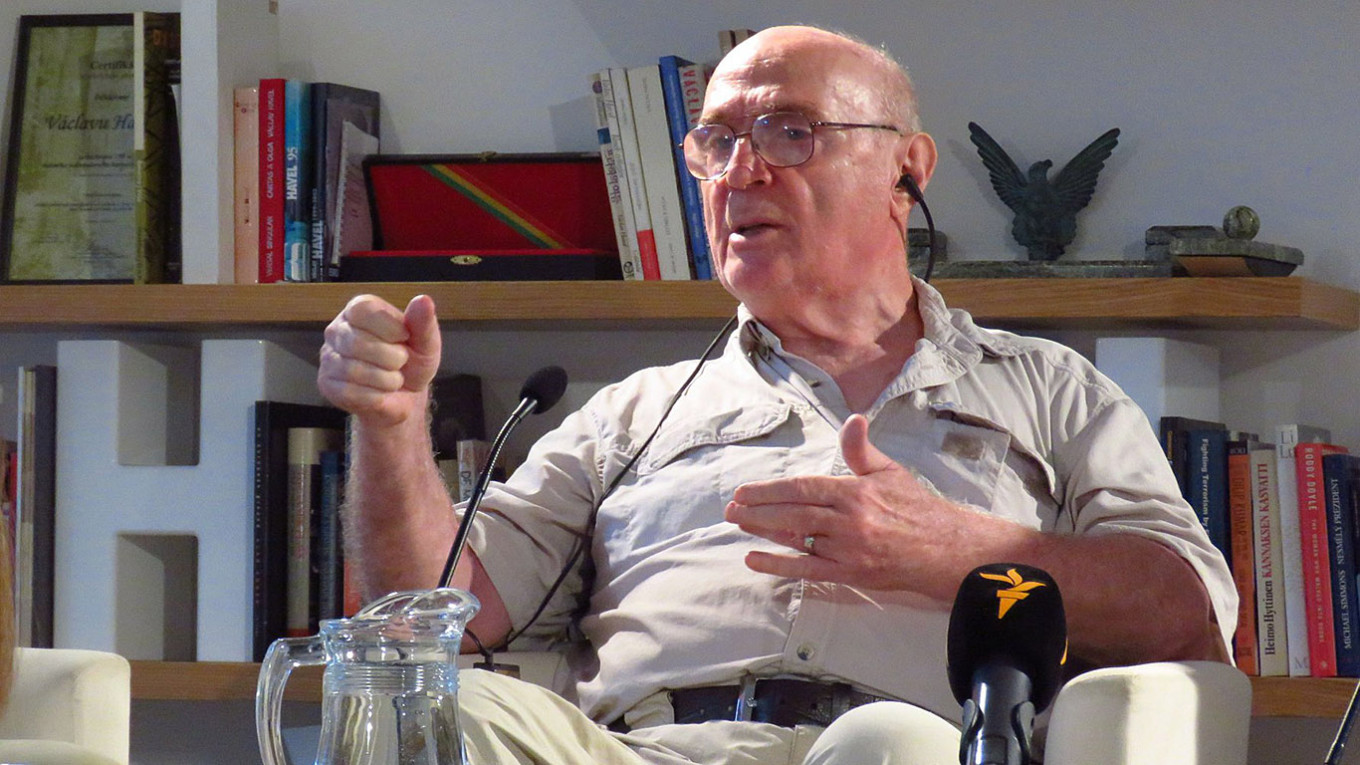

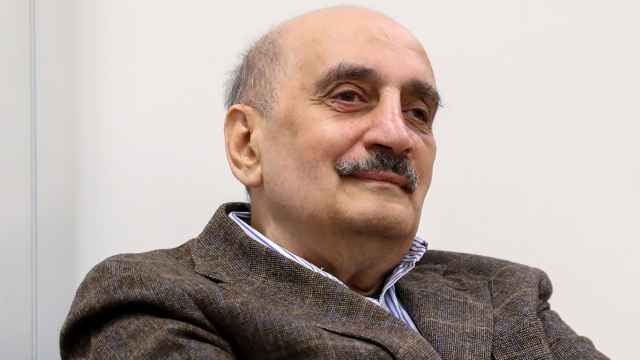

Pavel Litvinov is a former Soviet dissident and human rights activist who played a key role in protesting state repression in the U.S.S.R.

In 1968, he was among the eight protesters who staged a rare demonstration on Red Square against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. For this protest, which lasted only a few minutes before KGB agents arrested the participants, Livinov was sentenced to five years of internal exile.

Coming from an elite political family — his grandfather, Maxim Litvinov, was Josef Stalin’s foreign minister in the 1930s — he remained a vocal critic of Soviet policies until the country’s dissolution.

In 1974, he emigrated to the United States, where he continued his advocacy for human rights.

Now living in New York, the 84-year-old retired math and physics teacher closely follows global events.

The Moscow Times spoke with him about freedom of speech in modern Russia, the Soviet Union and the U.S., including Donald Trump’s decision to dismantle Voice of America — a media outlet the Soviet dissident viewed as one of the few uncensored sources of information.

This speech has been edited for length and clarity.

“The closure of VOA is a small detail in what the Trump administration and Trump himself are doing right now. But for us, it matters. VOA has been one of the most important sources of information and commentary throughout my life.

What is VOA for us? In Russia, it was known as foreign radio. That included the BBC, VOA, Deutsche Welle and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. These were all sources of information that came from abroad — foreign radio or, as the Soviet authorities called them, ‘hostile voices.’

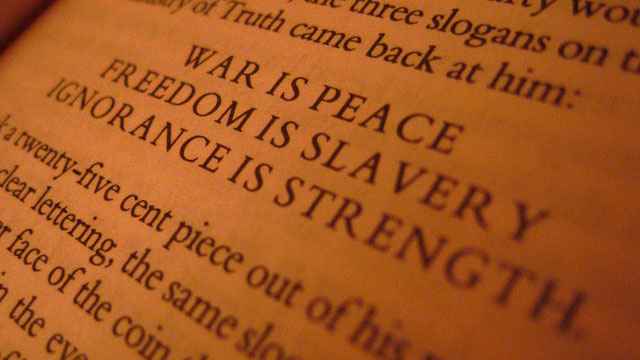

Why was this so important? In most cases, people don’t listen to foreign radio — they don’t need foreign media. In the U.S., people usually read only American newspapers. But in Russia, there was essentially just one newspaper and one radio station. Yes, they had different names — like Pravda, Izvestia or the magazine Ogonyok. But they were all controlled by the same source: the Communist Party, which trained Soviet journalists and editors on what could and could not be reported. So when we listened to foreign radio, we knew we were hearing something that was not approved by the government. And that was almost the only free source of information because the main source — the official press — was censored. There were special people who read every book before publication, who checked everything.

How did VOA even reach us? We listened to it on shortwave radio. It was often difficult because, at times, these ‘hostile voices’ were jammed by the Soviet authorities. They would broadcast noise over the same frequency or play a Soviet program at a higher volume to drown it out. The fact that we managed to listen to it was almost a miracle. Usually, you had to buy a very good radio receiver. Sometimes, we would leave the city to listen because jamming was stronger in Moscow.

That radio gave us life. We became familiar with [Nobel Laureate and Russian writer Alexander] Solzhenitsyn’s work when he was already banned in the Soviet Union because it was broadcast by VOA. We listened to Louis Armstrong, whom we loved — his unforgettable voice. It all mattered so much to us.

When I joined the demonstration on Red Square in 1968 against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, VOA and the BBC started reporting on it. That was when the jamming resumed — something we hadn’t seen in years in that time. On the day of the invasion, they turned the jamming back on and it didn’t stop until the end of the Soviet Union.

Now, I live in a free country, in America. And the fact that America no longer needs VOA only proves that, in reality, VOA is needed in America itself. That is the sad conclusion.

Press freedom is what distinguishes a free state from an unfree one.

For example, Russia is now waging a brutal, senseless war against Ukraine — a war Moscow started for no reason. The official press cannot remain completely silent about what’s happening, so it simply lies.

Freedom — whether in Russia or in America — depends on knowing something beyond the official narrative. American presidents have never liked critical press — no one likes being harshly criticized. But they have rarely tried to ban it.

A free press is life and it must be fought for.

I have fought for it all my life and believe that nothing is more important.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.