In January, Ingushetia natives Ramzan Padiev and Batukhan Tochiev were arrested on charges of murdering Lieutenant General Igor Kirillov, the highest-ranking Russian military official to be assassinated since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Kirillov and his assistant were killed in mid-December 2024 when a bomb went off outside his apartment building in southeastern Moscow. While Ukraine’s security services claimed responsibility for the assassination, Russian officials claim 29-year-old Uzbek national Akhmad Kurbanov carried out the murder with the aid of Padiev and Tochiev.

Russian media, citing security forces, identified the two young men as members of the Batal Hajji brotherhood, a closed Sufi Muslim order founded by Ingush Sheikh Batal Hajji Belkhoroev in the 19th century.

Padiev and Tochiev are not the first members of the order to have been linked to a major terrorist attack in Russia. Last year, four members of the brotherhood were arrested on suspicion of selling weapons and ammunition to the perpetrators of the deadly March 2024 attack on the Crocus City Hall concert venue, which left 145 people dead and hundreds more wounded.

Regional analysts and human rights defenders agree that the recent allegations against Batal Hajji members are part of a years-long campaign by Russian security forces aimed at driving the once-all-powerful brotherhood underground.

‘The golden era’

“One cannot become a member of the Batal Hajji order, one can only be born into it,” explained Isabella Evloeva, an Ingush journalist and founder of the independent news outlet Fortanga.

“Even if you marry someone from the brotherhood — though only a few have been able to do that — you will never become a part of it,” she said.

Sheikh Batal Hajji Belkhoroev, the religious brotherhood’s founder, was a pupil of the Chechen Muslim mystic Kunta-Hajji (Kunta Kishiev). This relationship translated into a bond between their respective followers that would influence the faith of Belkhoroev’s followers centuries later.

Because Batal Hajji Belkhoroev opposed his homeland’s occupation by Russia, Tsarist authorities sent him to forced exile in the modern-day Kaluga region, where he died in 1914.

Only one of the Sheikh’s seven sons, Qureysh Belkhoroev, survived subsequent Bolshevik repressions, becoming the sole bearer of the Belkhoroev lineage. Today, his descendants assume the leading positions in the order that is estimated to have around 20,000 members.

“Members of the Batal Hajji brotherhood often do not identify as Ingush. They are a very closed-off group,” said Evloeva. “In the past, they would not eat food prepared by other Ingush or bought from a store. They would cook separately. Do you know the Muslim concept of halal? For them, anything prepared by other than their own was considered not halal.”

Chechen-Ingush political analyst Islam Belokiev likened the Ingush order to the Amish, except that the former “do not reject modern conveniences and clothes.”

“Their unity allowed them to survive the harshest years of repression by the Tsarists and then the Soviets,” Belokiev told The Moscow Times. “When the opportunity arose, they began engaging in entrepreneurship…They became highly influential figures in Ingushetia, making enemies but also finding many eager business partners.”

The Batal Hajji order’s “golden era” coincided with the local presidency of Murat Zyazikov, when brotherhood members occupied key government roles but also obtained a near monopoly on Ingushetia’s construction industry, according to journalist Evloeva.

The first warning signs of the brotherhood’s potential downfall came when the Kremlin appointed military man Yunus-bek Yevkurov to head Ingushetia in 2008.

“Occasionally, they faced raids — sometimes their jewelry stores or other businesses would be raided, and valuable items confiscated,” recalled Evloeva. “But there was nothing like the repressions happening now. The crackdown truly began after the murder of Ibragim Eldzharkiev.”

‘An act of revenge’

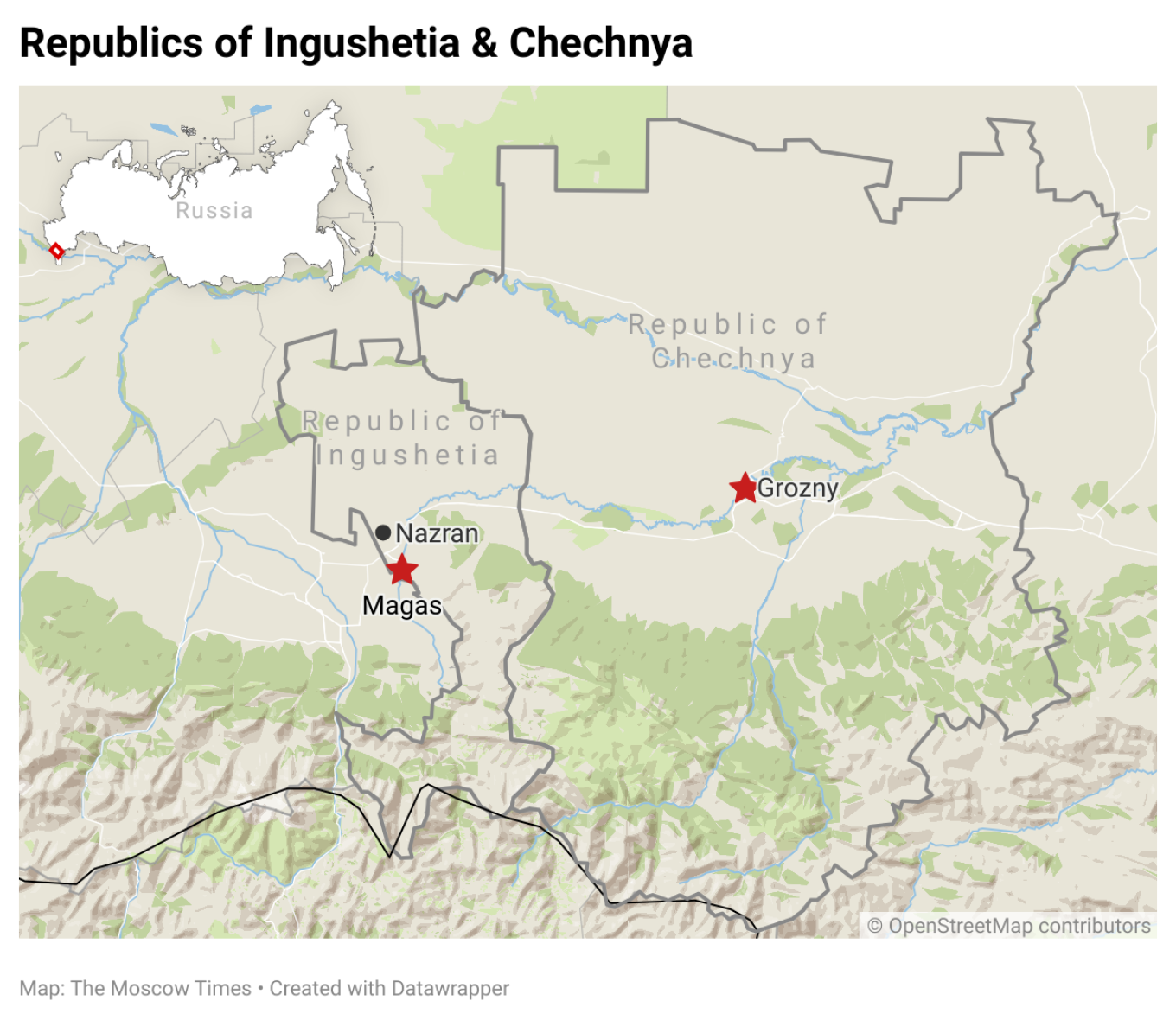

On Dec. 31, 2018, Ibragim Belkhoroev, the great-grandson of the order’s founder, was killed in a shooting attack on his car in Nazran, Ingushetia’s largest city.

Media and observers speculated that the murder may have been linked to Batal Hajji’s conflict with Ibragim Eldzharkiev, the head of Ingushetia’s Center for Combatting Extremism, a special unit within Russia’s Interior Ministry.

Less than two weeks after Ibragim Belkhoroev’s murder, Eldzharkiev’s car was attacked by gunmen near the border with Chechnya. The incident left three policemen injured, while Eldzharkiev emerged unscathed.

In November 2019, Eldzharkiev and his brother were shot dead at a parking lot in a residential neighborhood in Moscow. The security officer’s murder was immediately linked to his standoff with members of the Batal Hajji brotherhood, triggering home searches and mass arrests of the Sufi order’s members.

Eleven men were arrested in connection with Eldzharkiev’s murder. Charges against them included “leadership and participation in a terrorist group,” even though Russian authorities added the Batal Hajji order to their now-extensive list of terrorist organizations after the court proceedings already began.

“The repressions [against Batal Hajji order members] were an act of revenge by law enforcement authorities. They did not forgive the murder of a high-ranking police officer,” said journalist Evloeva, noting that “no member” of the order has ever experienced the same level of pressure.

“All high-ranking [order members] lost their positions — deputies, businessmen, ministers — everyone they had in power. And what is still happening today is a direct consequence of the murder of Ibragim Eldzharkiyev,” she added, referring to the implication of the brotherhood’s members in the Crocus City Hall attack and the murder of General Kirillov.

The Chechen patron

In November 2022 — amid fresh arrests of high-ranking members of the Batal Hajji order — Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov released a video in which he called members of the brotherhood victims of a “coordinated smear campaign.”

“To me…followers of the esteemed Batal Hajji have always been and will always remain close brothers,” Kadyrov said in a video where he appeared seated next to Akhmed Belkhoroev, a former member of Ingushetia’s parliament and one of the order’s leading figures.

“If they are terrorists, then I am terrorist number one. If they are a cult, then I am the cult’s number one member because we are of one faith,” Kadyrov added, referring to the order’s link with Chechen mystic Kunta-Hajji.

Members of Batal Hajji have long maintained a close relationship with Kadyrov. In 2014, Kadyrov even ordered the naming of a major mosque in Chechnya after Sheikh Batal Hajji Belkhoroev.

Amid the repressions, many members of the Ingush order sought refuge in Chechnya, the neighboring republic ruled by Kadyrov with an iron fist.

Political analyst Belokiev said Kadyrov’s willingness to accept the outcasts was purely a matter of business interests, the benefits of which could be reaped after normality is restored in Ingushetia.

“At the time many believed that the repression against the Batal Hajji brotherhood would soon subside, especially since Kadyrov himself had intervened on their behalf. But that was not the case,” said Belokiev.

In December 2022, the first group of volunteer fighters enlisted in the Batal Hajji Rapid Response Unit, a part of Kadyrov's Akhmat military unit within the Russian army, was sent to the front lines in Ukraine’s Kherson region.

Around 100 members of the order have joined Kadyrov’s forces fighting in Ukraine, according to Meduza.

Despite the image boost that aiding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could provide to both the outcast order and Kadyrov himself, patronage of Batal Hajji members could still come at a cost for Chechnya’s leader.

By linking the brotherhood’s members to the Crocus City Hall attack — which Russian officials claim was orchestrated by Islamic State affiliate ISIS-K — authorities are essentially drawing a link between the Sufi order and international terrorist organizations, analysts say.

“[For Russian security forces], this is an opportunity to undermine and discredit Kadyrov, portraying him as someone who supports terrorists allegedly responsible for the attack on Crocus City Hall,” said Belokiev. “Kadyrov knows [how this could play out] and already mentioned in private circles that he would not accept Batal Hajji members accused of carrying out the Crocus City Hall attack or the murder of Kirillov.”

Kadyrov’s links with Batal Hajji aside, some parallels between the fate of the Chechen nation and that of the brotherhood are difficult not to notice.

On the front lines in Ukraine, members of the order could face their own in combat as a few “have been fighting against Russia on Ukraine’s side since 2014,” according to Belokiev, a former press secretary for the Chechen Sheikh Mansur Battalion that fights for Kyiv.

And the situation for those remaining at home rings close to the fate of Chechens in Russia in the 1990s and 2000s.

“During the war in Chechnya, there was a tendency to blame all crimes in Russia on Chechens…The story with the Batal Hajji order is the same,” said journalist Evloeva. “They are simply being scapegoated. This is like a witch hunt.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.