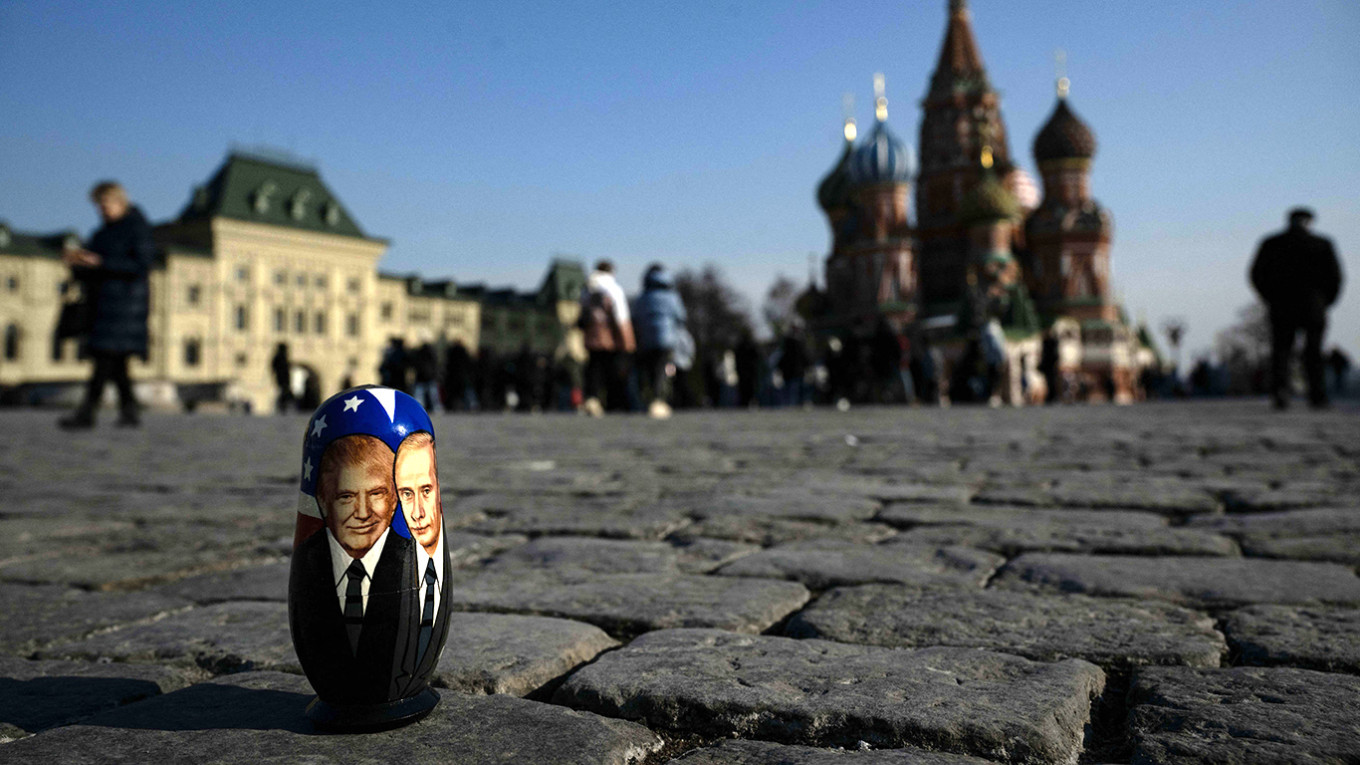

President Vladimir Putin’s move to allow major U.S. hedge funds to divest their frozen Russian securities marks a tentative first step in Russia’s bid to re-enter global capital markets. But do not be fooled — this is far from a breakthrough.

With trust between Russia and the West shattered and bridges burned, rebuilding economic ties will require far more than a few opaque and dubious deals. Following the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s access to global financial markets evaporated as sanctions severed its banks from international systems and the country saw a mass exodus of capital. The path to reintegration will be long, arduous and fraught with significant obstacles.

On March 17, Putin authorized a U.S. hedge fund 683 Capital Partners LP to purchase securities in Russian companies from 11 other funds, mostly based in the U.S. and Britain.

In addition, two Russian companies linked to Kremlin-controlled Sberbank, Tsefey-2 and Sovremennye Fondy Nedvizhimosty, are now authorized to buy 683 Capital’s securities without needing Putin’s approval.

The decree follows Putin’s August 2022 order prohibiting U.S. and other investors from countries deemed “unfriendly” by Russia from buying or selling securities in Russian companies in the energy, fuel and banking sectors without his personal approval.

The arrangement should raise alarm bells. Participating Western funds are offloading their holdings to an intermediary, which will then resell them to Russian entities. This setup hints at two key motives: sheltering Western sellers from sanctions and potentially lining the pockets of the middlemen in the process.

The decision to let U.S. hedge funds exit Russian investments comes as reports suggest the White House is considering incentives for Moscow, including the potential recognition of Crimea as Russian territory. It is a shabby move and a woeful trade-off.

The blue-chip hedge funds granted the green light to exit their frozen investments are primarily U.S.-based, including major players like Franklin Templeton, Jane Street, GMO, as well as the Scottish firm Baillie Gifford. Given the restrictions on selling and the heavy sanctions on Russia, these funds had likely considered their holdings worthless. Additionally, any dividend or coupon payments on bonds were trapped is unable to flow through further the financial system.

Other major fund managers like Blackrock, which is reported to have almost $1 billion stuck in Russian markets, will be keeping close tabs on developments. International asset managers, hedge funds, and pension funds are believed to have around $90 billion in equities locked in Russia’s financial system.

Pioneering investors in Russia, such as Prosperity Capital and East Capital, will be privately raging to miss out on an exit. The two Swedish hedge funds were long-term investors over decades and had billions invested in diverse portfolios with boots on the ground until Putin launched the invasion of Ukraine.

Putin wants to lure Western businesses back to Russia. But his message at the annual congress of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs on March 18 came with veiled threats.

The Kremlin’s promises to "guarantee" the safety of foreign investments are anything but reassuring. The clear underlying warning is that Western firms should not expect the same protections they enjoy in their home countries.

In Putin’s Russia, the freedoms of trade, payments and capital flows are no longer guaranteed. As he bluntly put it, “What was, will no longer be,” and there is no hope of relying on Western legal mechanisms to protect investors.

The shutdown of Russian companies’ access to global capital markets and the sovereign government has severely restricted their access to international financing. Sanctions have severed crucial capital flows, making it difficult to raise funds, service debt, or invest in growth. With limited foreign investment and financial market access, Russia’s economic outlook is now severely constrained, forcing businesses to rely on increasingly unstable and extortionate domestic funding.

However, the return of Donald Trump to the White House has sparked hopes that the U.S. may soon ease sanctions. As a result, the ruble has rallied by 36% against the dollar this year, while Russian stocks have experienced a strong rebound.

The FT reported last week that Western hedge funds are desperately looking at ways to gain exposure to Russian assets. Some have piled into the Hong Kong shares of the Russian aluminum producer Rusal, while Austria’s Raiffeisen and Hungary’s OTP Bank have also enjoyed a bounce due to their exposure to Russia.

Banks and brokers are also offering bets on rouble fluctuations settled in dollars, allowing investors to sidestep direct exposure to Russia. These non-deliverable forwards are commonly used for trading currencies that are difficult to access outside their home countries.

However, it would be a mistake to believe that rebuilding Russia’s bridges to global capital markets would be easy after they were torched by war and a tsunami of sanctions. These financial instruments remain largely off-limits to international funds, making any talk of quick reintegration unrealistic.

The Kremlin's latest push to rejoin international capital markets may echo Dmitry Medvedev's doomed effort to position Moscow as a global financial center to rival Frankfurt and London. That vision crumbled under the weight of corruption, political instability and the very same isolation Russia now faces.

In 2011, Wall Street titans like JP Morgan's Jamie Dimon and Blackstone's Stephen Schwarzman were appointed to committees tasked with advising on the infrastructure needed to attract financial flows to Moscow. Yet, their efforts proved to be a Potemkin-like mirage, quickly shattered by the annexation of Crimea.

Medvedev’s vision of Moscow as a thriving financial hub was always a pipe dream, much like the Skolkovo Innovation Center’s ill-fated attempt to ape Silicon Valley. Both initiatives were doomed by systemic flaws and the absence of the rule of law. As a former lawyer, Medvedev even promised to eradicate "legal nihilism"— a pledge that now seems absurd given his recent embrace of turbo-nationalism.

Russia’s path back to international finance won’t be a revival of Medvedev’s fantasy but rather a long, painful struggle to repair bridges that were thoroughly torched.

Foreign investors attempting to return to Russia are not just risking their clients’ money. They are putting their own lives on the line. The scandalous arrest of high-profile figures like Michael Calvey, the American founder of private equity firm Baring Vostok, as well as the treatment of opposition leaders and activists evoke echoes of the Stalin-era purges of 1937.

Anyone doing business in Russia is gambling with their own money, their clients' money and the safety of themselves and their employees.

Russia is un-investable and will remain so until there is regime change. Anyone willing to pour money into that environment is taking a reckless risk. If they are managing other people’s money, they are failing in their most basic duty as fiduciaries.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.