According to the most conservative estimates, 1,000 people gathered for this month’s Russian opposition protest in Berlin.

The small anti-war rally in Berlin sparked two burning discussions: whether it was acceptable to march with the Russian flag and how to treat the column of the Russian Volunteer Corps (RVC), a far-right military unit fighting for Kyiv, who came of their own volition.

Both discussions, about symbols and allies, are fundamental because they raise questions that cannot be ignored: Whose side is the opposition on? Who do they represent and where do they see their political future?

As political scientist Viktor Sergeev and philosopher Nikolai Biryukov wrote at the beginning of the century, Russian political culture is built on fear of any social and political schism. These are impossible to avoid. But democracy allows these schisms to be contained and directed in productive ways.

The Russian opposition has been shaken over the past year by schisms involving Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the FBK, Maxim Katz and Leonid Nevzlin. Instead of being a debate about values, these rifts reflect an internal struggle for conformity.

The Russian opposition’s obvious desire to act as a center of gravity for all opponents of President Vladimir Putin's aggression is understandable. But at the beginning of the fourth year of a full-scale war, this seems insufficient.

The Russian opposition let itself become complacent by clinging to the old myths about all-out international support for Ukraine, Russia's isolation and the weakness of Putin's regime.

We are now seeing a hard collision with reality as these myths collapse. The idea that the opposition could use this crisis to ride into power on a white horse did not work out. It could not happen, if only for the reason that they are fighting for their existence, not for the “beautiful Russia of the future.”

Amid all this, the exiled Russian opposition faces the question of how to support Ukraine’s struggle while still hoping for a political future in Russia.

The discussion about the Russian tricolor is the easiest debate to get caught up in. It is not technically difficult to modify the flag itself and promote a new unifying symbol.

The presence of the Russian Volunteer Corps poses a more complicated problem. Almost everyone in Russia knows someone who has fought in the war, been injured or killed. For every one of these people, any Russian who fights against their friends and countrymen is a traitor.

Of course, the RVC considers themselves warriors who are fighting against the regime. But this position has no political future inside Russia.

After the war ends, veterans of the Russian and Ukrainian armed forces may one day be able to meet, as veterans of the Wehrmacht and the Red Army did in the 1990s. But former Vlasovites who fought under Russian command were not invited to these meetings.

Moreover, the RVC is not made up of leftists and liberals, or even right-wing populists, but staunch ultra-rightists, white supremacists and, in some cases, even neo-Nazis. Allying oneself with such people is not only toxic in Russia, but in Europe as well.

The RVC are undoubtedly brave patriots of Ukraine who have proved with their blood their readiness to fight for it. They have a potential future as representatives of a minority Russian viewpoint and perhaps even as a far-right party in the EU.

But they will not return to Russia. Even in the unlikely case of a civil war, their future is a mass grave somewhere near Belgorod — because the public considers Russian traitors even more worthy of death than the Ukrainian enemy. No politician will be able to convince people otherwise.

For several centuries now, European politics has been centered on the idea of the political nation, for which the definition of “one's own” is fundamental. Wars intensify national sentiment, which serves to strengthen the state apparatus. Think of World War I and its aftermath.

All that is in the ideological asset of the RDK are the ideas of Slavic unity, which, to put it mildly, are marginal in Russia and, at least, the leftists and liberals have nothing to catch on this field.

It may seem strange to some to distance oneself from those who put their lives on the line for Ukraine while the liberal opposition is active only in the media. The problem is deeper for the opposition because it calls into question whether they are for Russians or Ukrainians.

Despite justifications that the war is an expression of the Putin regime’s worst impulses, an increasing number of anti-war Russians inside the country are starting to see the war in abstract terms and are warming to the idea of peace at any cost to Ukraine.

Some in the opposition might also want to join in criticizing Ukraine, hoping that this would broaden support inside Russia and encourage a return. Even if they direct this criticism at President Volodymyr Zelensky, such a move is fraught with the risk of eroding support.

The war will not be over when the guns fall silent. Some think that Putin will use any respite to rearm for a future war, while others hope that he is really tired and the most pro-war factions of the government will stage a coup and topple him.

If people are reluctant to criticize the RVC for fighting for Ukraine on the battlefield instead of in front of a computer, that is a mistake.

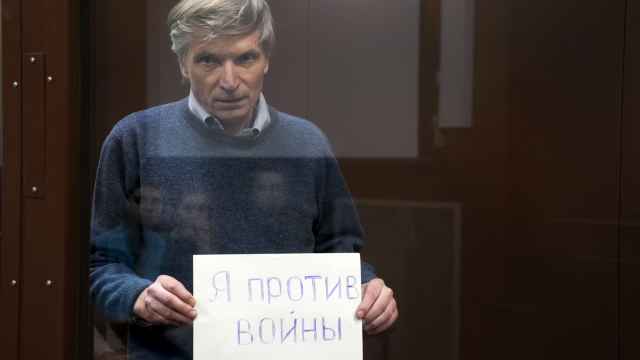

The responsibility of a Russian is to be against the war; not to participate in it; to dissuade others from doing so; to oppose his government; and to try to minimize the damage to the Ukrainians.

Yet it is key to remember that the future of Ukraine does not depend on the Russian anti-war opposition, who cannot build Kyiv a powerful military-industrial complex, send it arms or even stop Putin. Ukrainians themselves are in no hurry to call Russians to their cause.

Anti-war Russians have ample opportunities for collective or individual action. The situation is somewhat different for politicians. No faction of the Russian opposition can take political responsibility because they are not at the levers of power. Yes, Russians are wrongly saddled with collective responsibility for the war regardless of their beliefs and actions. But the only people who can take on that responsibility are the people elected to represent them.

Turning into a Ukrainian patriot is not the way to do this, but it is still possible to remain an ally of Kyiv. But many Russians will identify more closely with people they consider their own, even if they were one of the paratroopers massacring civilians in Bucha. Not because they lionize them — rather, because they see them as fellow citizens they should take responsibility for.

Therefore, the Russian opposition in exile has three strategic options left.

The first is to lean into Russian patriotism and how to build up a competitive advantage for when they return to Russia. In that case, it will have to seek the support of those who remain in Russia or nostalgic emigres. The opposition's PR agenda is focused mainly on those who have left, and they more or less don't care about those who have remained. Doing so would get the RVC out of the way and negate some criticism of the opposition from Russians in the country.

With a strategy like this, there is no point in paying attention to those who have left and Russian speakers who are not going to return and who prefer to be patriots of Ukraine. They are not the opposition’s electorate, not your social support. Therefore, if Yashin, Kara-Murza and Navalnya hound the RVC out of their next rally, it would be a strong statement about who is part of their vision for Russia.

It is unlikely that the opposition will return to Russia in the foreseeable future. But making that the goal is the only way they will ever be able to take political responsibility for their country’s aggression. Anything else would just be empty words. Apart from the costs of dubious allies, the main obstacle is the lack of examples of when the Russian opposition can confidently say they represented their own.

The second is to forget about Russia and turn into a European political party fighting for the interests of the Russian diaspora. Here the logic of choosing partners will differ, although contacts with pan-Slavists will repel leftists and liberals. This path smacks of visionaryism, but if there are people, grassroots solidarity networks, and a common information space, why can't all this be used for a new political platform?

But there is a third way which is, unfortunately, the most realistic one: The Russian opposition could remain an amorphous diasporic group that is more concerned about its survival than any actual political struggle.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.