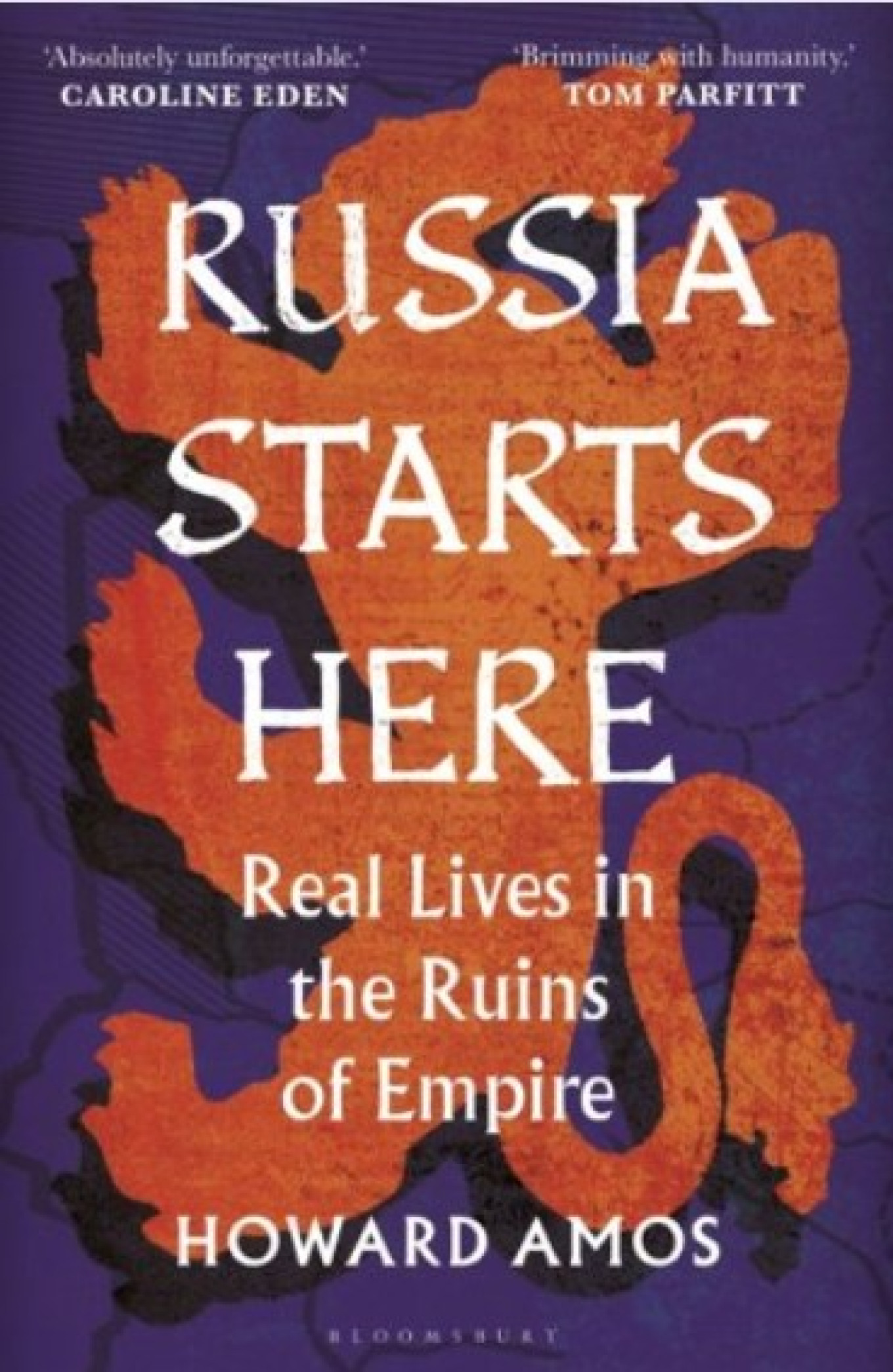

“Russia Starts Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire” is Howard Amos’s debut book, but it doesn’t read like one. That’s not surprising. He is a seasoned journalist and editor who has written for The Guardian, Newsweek, Foreign Policy, and The Associated Press. Amos was also a journalist and editor-in-chief of The Moscow Times.

"Russia Starts Here" focuses on a single Russian region — the Pskov region. Located on the border with Estonia and Belarus, it is the westernmost point of Russia (not counting the exclave of Kaliningrad) — the place where Russia literally "starts." The Pskov Region has played an important role throughout Russian history and does so again today, sitting on NATO’s border at a time of heightened tensions with the West.

There is no single dedicated history chapter, but Amos weaves historical details throughout the book, allowing readers to gradually piece them together — from the medieval veche (parliamentary) republic that was part of the mighty Hanseatic League to the nationalist resurgence of the 1990s, when an LDPR candidate won the governor’s post.

Amos has a personal connection to Pskov, having spent a few weeks helping at an orphanage there on his first trip to Russia as a student in the U.K. The chapters about the orphanage and the psych ward in nearby Bogdanovo are heart-wrenching. The orphanage was also where Amos met the protagonist of another chapter — Dmitry Markov, a remarkable photographer, who recently died of a drug overdose.

"Russia Starts Here" explores religion in depth — as is appropriate since the Pskov region has been known for its monasteries for centuries. One of them, Pskov-Caves Monastery in Pechory, just five kilometers from the Estonian border, features in several chapters of Amos’s book.

The chapter titled “Director of Religion” is devoted to Father Tikhon Shevkunov, Putin’s alleged “spiritual father” (dukhovnik). Tikhon, a bestselling author (“Everyday Saints and Other Stories”), claims that Pechory was the site of his spiritual “birth.” Another chapter tells the story of two brother priests whose lives were linked to the same monastery.

One of the most intriguing chapters is the last, which is devoted to the Seto people, a minority group split between the Pskov region and Estonia. The Seto are Orthodox, but their faith incorporates elements of paganism, and Pechory is one of their most sacred sites. Amos chronicles the struggles of a family divided by the border and their eventual decision to move to Estonia after the pandemic.

At times, Amos’ prose takes on a poetic quality, as in the chapter titled “Back Country,” where he hikes with a friend from Staraya Russa to Lake Pskov — a journey of about 200 kilometers. This travelogue brims with vivid descriptions of nature and encounters with people along the way.

The two friends pass by the former estate of Fyodor Dostoevsky, the Nikandrova and Krypetsky monasteries, and Yelizarov Convent, where Philotheus lived — the monk who coined the famous phrase: “Two Romes have fallen, a third stands, and a fourth there shall not be.” The third Rome is, according to Philotheus, Moscow.

There’s only one chapter devoted to the war in Ukraine — appropriately titled “War” — but references to the invasion surface throughout the book. When Amos speaks with his subjects — from politicians to retirees in an abandoned village — the topic almost always comes up. Most of those who explicitly voice their opinion support the war.

Among the recent flood of Russia-themed nonfiction, Amos’ book stands out. Unlike many others, it is not focused on the war in Ukraine or Putin’s politics, yet it offers a thorough and vivid portrait of contemporary Russia, told through the lives of people from all walks of life.

Russia Starts Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire

From Chapter 17: Divided Lives

Tiina Süvaorg’s eyes were a washed-out blue, a few shades lighter than her dress. As we sat in the dappled sunlight outside a café in southern Estonia, gusts of wind spun her dyed blonde hair in all directions and she toyed with the pink plastic slip-on shoes dangling from her feet. Born in a small village in Pskov Region, Tiina moved to neighbouring Estonia in the 1990s and built a life, raising three children who are now in their late teens and early twenties. But her ancestors are all from Russia, her husband grew up in Russia and, until a few years ago, her parents lived in Russia.

Just a few kilometres away from us was the Estonia-Russia border that has marked the eastern edge of the EU and NATO for more than two decades. Heavily patrolled and monitored, this border has become increasingly militarized amid the dramatic collapse of relations between the West and Russia, looming ever larger in the lives of those who reside in its shadow. Hard borders erase ambiguity. But Tiina is one of a fast-dwindling number of people who would be equally comfortable on either side.

Tiina is neither Russian nor Estonian. She is Seto. A tiny ethnic group of some 10,000 people, the Setos have inhabited these borderlands for centuries, retaining their own distinctive traditions, beliefs and culture. Like the Russians to their east, Setos are Orthodox Christians (distinguishing them from the largely Lutheran Estonians). At the same time, they are a Finno-Ugric people like the Estonians and their language, written in Latin script (not Cyrillic), is closer to Estonian — making it incomprehensible to Russians. Historically, some referred to the Seto as ‘Pskov Estonians’. Many believe it has been their location on the ‘edge of the world’ that allowed them to survive. If fate had dropped them a hundred kilometres further to the west or the east, the reasoning goes, they would have been assimilated long ago.

The Seto call their historical homeland Setomaa. Comprising some 17,000 square kilometres of forest, marsh and cultivated fields, Setomaa abuts the reed-choked banks of Lake Pskov in the north and Russia’s border with Latvia in the south. The capital, what the Setos call the ‘town of heaven’, is Pechory on the Russian side. The Caves Monastery is their most holy site.

The Seto are perhaps best known for their choirs, which preserve a polyphonic, multipart singing tradition, and the enormous conical silver brooches worn by women when in national dress. As part of the Seto ‘re-awakening’ in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the community invented a number of traditions including the election once a year of a ülembsootka — a ‘king’ or ‘regent’ — in a joyous, day-long festival in southern Estonia that includes a spoof military parade and cheese-making competitions.

For hundreds of years, Setomaa has been a border zone: a place where ethnicity shifts from Slav to Finno-Ugric; the language goes from Russian to Estonian; Estonian homesteads replace Russian villages; and religion switches from Orthodoxy to Lutheranism. Over the centuries, it was contested by Russians, Germans, Estonians, Poles and Swedes, and control has passed like a baton between different political masters, tugging the Seto first eastward, then westward, then back again.

But Setomaa was never physically split in two by a hard border until Estonia emerged as an independent country following the Soviet collapse. The modern frontier — with its razor wire, CCTV and crossing points — is a man-made barrier between villages, tearing at the fabric of Seto communities. It has even been referred to as the ‘Seto Wall’, a reference to the Berlin Wall. Above all, it has caused a corrosive imbalance of opportunity. Better economic and educational prospects in Estonia — not to mention access to the EU — have fuelled a Seto exodus from Russia.

The decision to move westward was a simple one for many Setos, because almost all were eligible for Estonian citizenship. Most young Setos also spoke Estonian. Moving to Estonia was the path taken by both Tiina and her sister, Marika. Listening to Tiina talk about her poverty-stricken upbringing in Russia, where the family relied on a horse and cart well into the 1990s, it was easy to understand her striving for a better life. Tiina went to university in Estonia’s second city of Tartu, and now works in a customs post on the Russian border; her husband is a long-distance lorry driver. They live in a large house outside Obinitsa, the centre of Seto life in Estonia. While we spoke, the keys to Tiina’s black BMW lay on the table between us.

The outflow to Estonia means that many Seto families have been split along generational lines. While young Setos and their children reside in Estonia, their elderly parents live out their days in Russia. There are no exact numbers, but about 4,000 Setos are believed to live in the 25 per cent of Setomaa controlled by Estonia. In Russian Setomaa, there are just a few hundred, mostly very elderly. This is not a process that happened overnight. Even twenty years ago, Father Yevgeny, a legendary priest among Setos who served in a Pechory church, told a documentary film crew that Russian Setos were dying out: he was conducting just one Seto baptism a year, and no weddings.

The day before meeting Tiina, I’d visited Saatse, which sits on a bit of Estonian land jutting into Russia. The patchwork of Russian, Estonian and Seto villages in this area flummoxed Stalin’s post-war planners, who could not find a logical way to draw the border. The result is a tourist curiosity called the Saatse Boot, where an Estonian road briefly runs through Russian territory. But I wanted to visit Saatse because I knew you could walk right up to the border. Despite spending so much time in Pskov Region, I had rarely glimpsed its international borders: Russia enforces buffer zones along all its frontiers and individuals require a permit from the FSB to enter (unless you are arriving in, or leaving, the country).

A five-minute walk from Saatse through an airy pine forest dotted with yellow chanterelles brought me to the demarcation line. The smell of pine rose in the morning sun, and it was quiet apart from a light breeze and the chirp of birds. While the Estonians mark the edge of their territory with black-and-white posts, the Russians use striped red-and-green ones with silver-imperial eagles. In places, Estonia has constructed large, green interlocking fences with spiked tips along the border. Here, however, there was just a single coil of razor wire and a jeep track. Locals told me that, when the war in Ukraine began in 2022, Estonian border guards stopped waving hello to their Russian counterparts on the other side.

Estonia has invested more and more in tightening security along its eastern border as relations between the West and Russia have collapsed. For much of the 1990s, large sections were mostly a symbolic boundary, with stories of people slipping across to visit friends and enjoy picnics, and a flourishing trade in smuggled vodka and cigarettes. Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, Ukraine in 2014, and then its full-scale war on Ukraine, however, made small, former Soviet states like Estonia nervous. And in recent years, Tallinn has ramped up its monitoring of what Russia is up to — and beefed up its border defences. While it is rare to see an Estonian patrol, the CCTV coverage is comprehensive enough that, I was assured, if you lingered at the border for too long, officers would quickly arrive on the scene.

Excerpted from “Russia Starts Here: Real Lives in the Ruins of Empire” written by Howard Amos and published by Bloomsbury Continuum. Copyright © Howard Amos, 2025. Used by permission. All rights reserved. For more information about Howard Amos and his book, see the publisher’s site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.