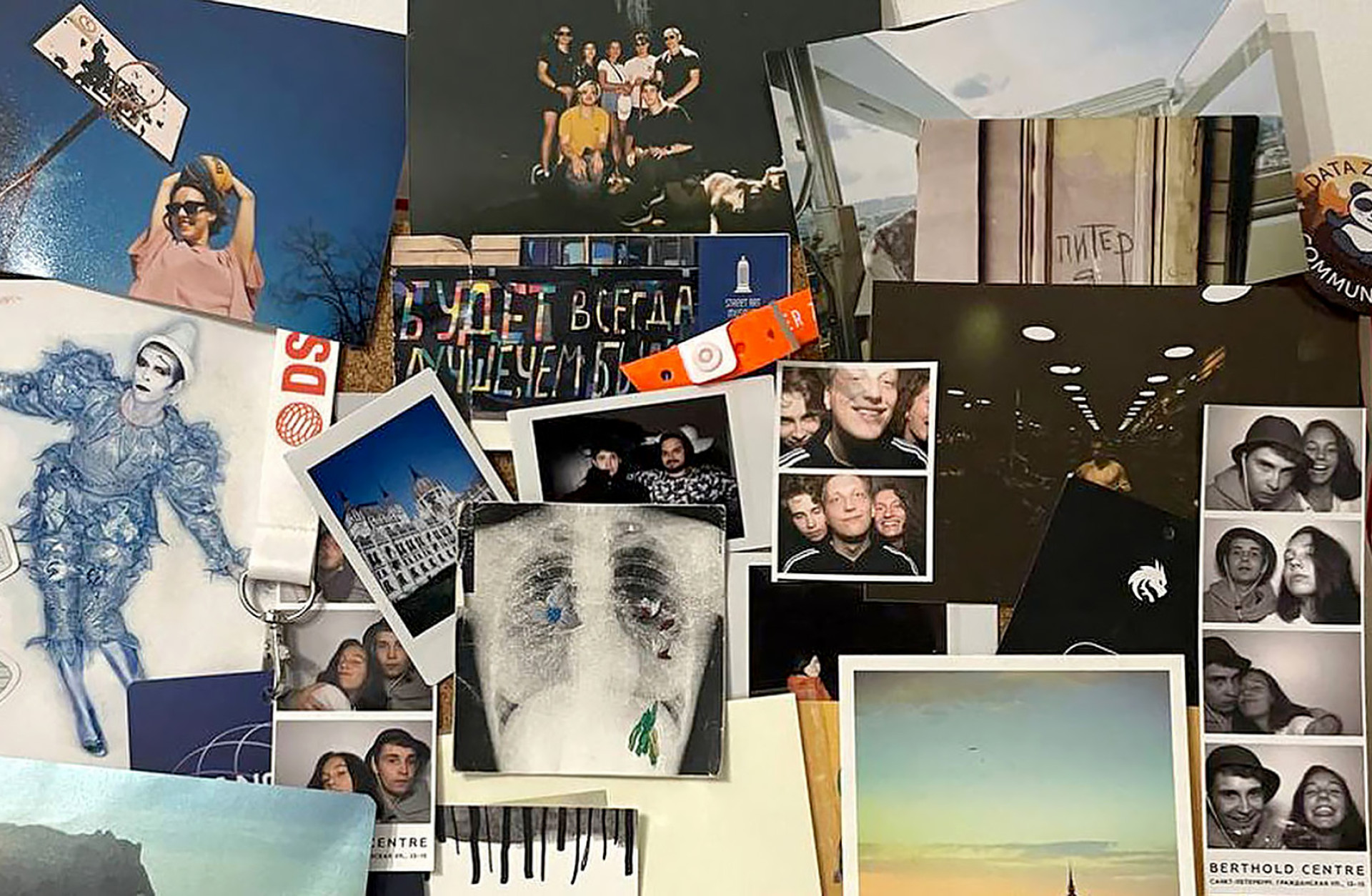

When she and tens of thousands of other Russians moved to Serbia following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, St. Petersburg-born museum curator Ulyana Dolmatova started sharing photos of migrants’ belongings on Instagram.

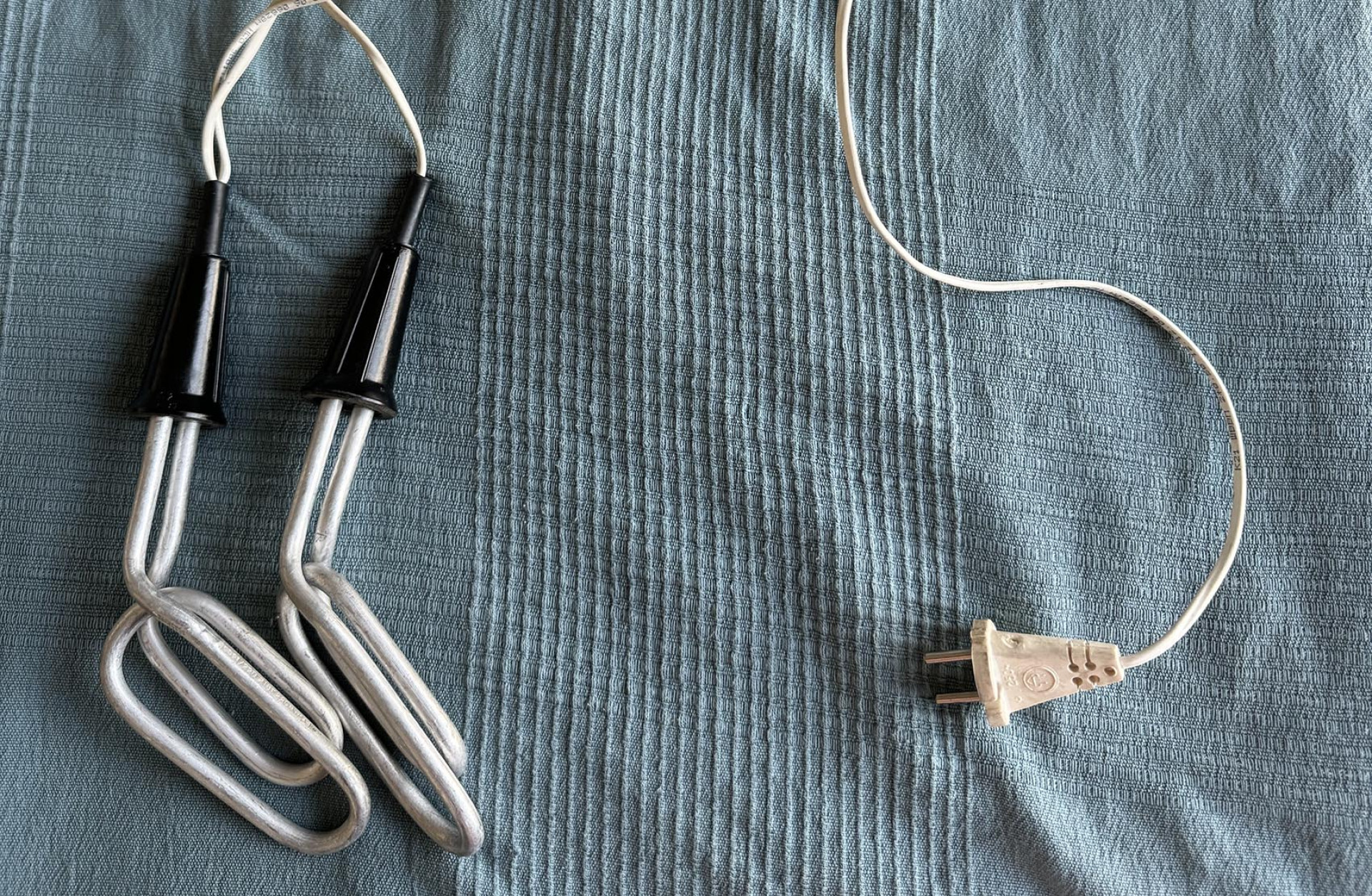

Most of the objects were handed down through generations, such as a pendant made from a grandmother's wedding ring, a grandfather’s watch and a Soviet boot dryer.

These items “symbolize consistency amid huge changes and the unknown,” Dolmatova wrote under the boot dryer.

The online Museum of Unforgotten Things is now full of cherished objects. Dolmatova wrote she wanted to create a space “to help people heal” from the experience of being uprooted.

“These things, torn from their usual environment, now become the keepers of our memory and evidence of a past life,” she said.

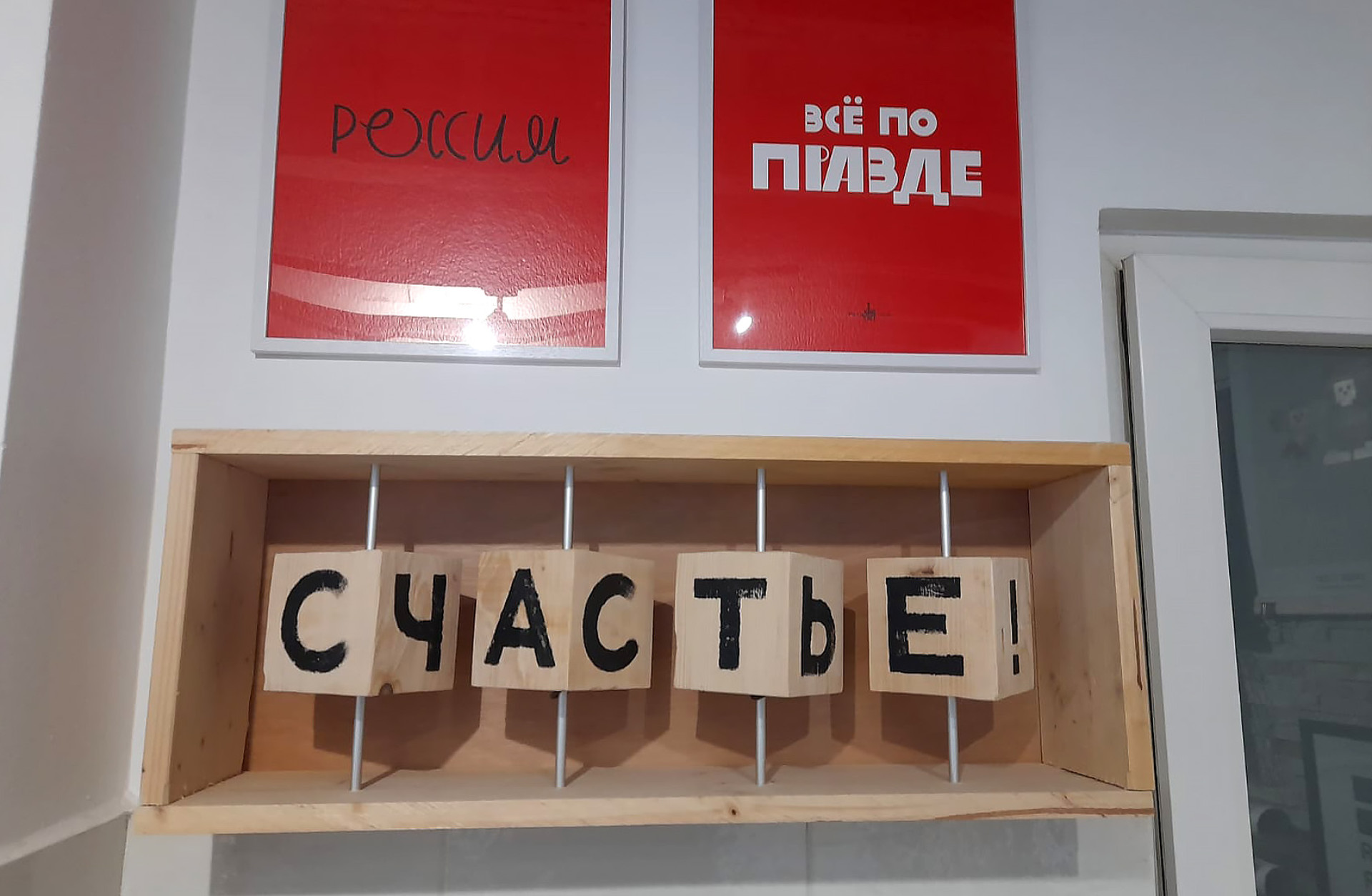

Her project is one of several that give voice to a generation of Russians who have left their homeland, perhaps for good. For now, the museum remains a virtual creation but Dolmatova hopes to find a bricks-and-mortar space in her adopted home of Belgrade. Around 200,000 Russians live in the Serbian capital out of an estimated 600,000 to 1 million people who left Russia since the war began.

Her museum may not yet have its own space, but Belgrade has become home to several Russian art galleries where artworks exploring migration are prominently displayed.

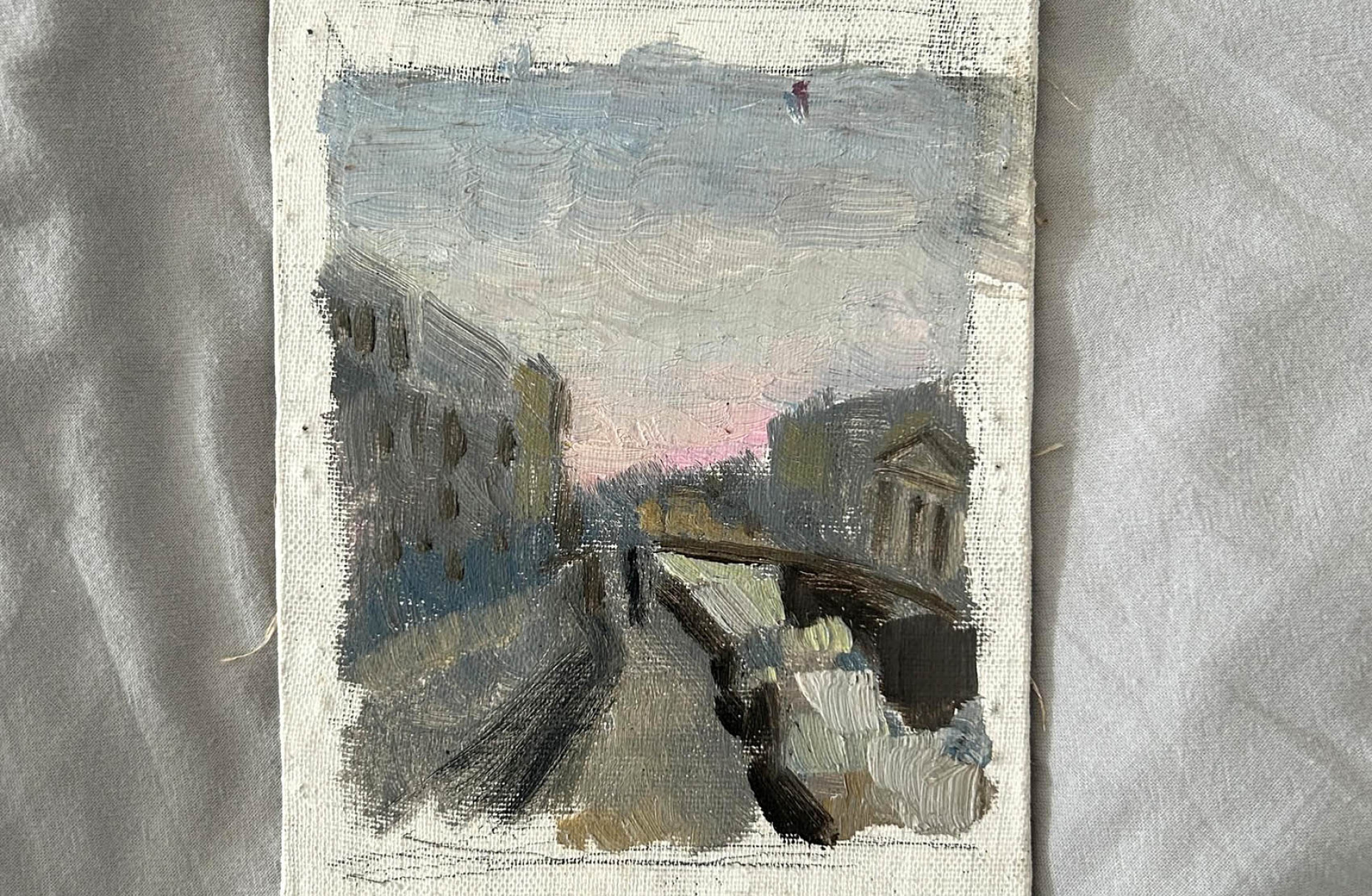

One of them, Nordistica, is hosting an exhibition by Russian artist Natasha Voronchikhina on the everyday experience of settling into a new culture.

Entitled Kesa ne treba (“I don't need a bag”), the paintings depict fruit that Voronchikhina bought at markets in Georgia from 2022-2025: first as a tourist who buys bright shiny fruits; then as a migrant who buys small bags of essentials; then as a long-term resident who bulk-buys onions, potatoes, has begun to speak the language and can interact with market sellers.

Another project is the independent publishing house Shell(f), set up in Belgrade and Montenegro by Laima Anderson and Ira Yuryeva, two editors who worked in St Petersburg publishing houses for a decade before leaving in 2022.

The project seeks to publish "all the things we couldn't write back home," said Anderson, including novels, essays, fantasy stories and poems that explore themes of family, home, emigration, loneliness and love.

Anderson published her memoir “Fontanka River Embankment,” — among the first to be published by a member of the wartime diaspora — in December. The collection of auto-fiction stories and essays describes the cities in which she had to live in the past three years, the objects she brought with her or left behind and painful farewells to people and places.

“Emigration is like an unhealed hole left after a tooth extraction, like period pains, like an inflamed muscle that restricts any movement, like eczema on the crook of the knee, like a graze, like a migraine," Anderson wrote in the introduction to the book. “You get used to it and try to do your usual things without paying attention, but the pain doesn't go away.”

Shellf was awarded a social outreach prize by Serbia’s Russian-language magazine Mapa Mag, a testimony to its resonance among the diaspora there.

Even before books about emigre experiences were published, Russians were sharing their relocation stories in microblogs on the Telegram channel I Miy Leteli (We Flew Away).

Active since 2022, the channel has 14,506 subscribers and receives hundreds of submissions from all over the world. Its founders have noted a “new unity” in the Russian community abroad and a shift in attitudes in how the diaspora connects.

“Before 2022, we repeatedly heard that Russians are the only people who move abroad and do not create a diaspora,” they wrote in the channel.

“Disunited, living in nuclear families, with no experience of joint political action…they say to newcomers, ‘we suffered, you will suffer too.’ But this notion changed with the mass exodus in 2022,” they continued. “The fifth wave of Russian emigration fostered a sense of community and a real network of support. Here is the new Russian diaspora, which is growing before our eyes.”

Through sharing personal stories, the founders saw an opportunity to break down the divisions that some people created by dividing emigres into “Februaryists” and “Septemberists” — those who left early in the war and those who left following the September 2022 mobilization.

For some, the platform helped people situate themselves as part of history; a continuum of diaspora past and present.

“Reading these memories, I recognize myself and people who thought and worried about the same things 100 years ago and 50 years ago,” said Anastasia, a subscriber in Georgia. “Yes, a lot has changed, we have the Internet and remote work, but, like our predecessors, we took our lives in one suitcase and left.”

Initially, stories sent to I Miy Leteli documented the immediate challenges of moving, such as packing, finding homes and the shock of sudden departures. Descriptions were vivid and personal.

In one entry, mother of two Arina Vintovkina described her chaotic departure to Montenegro: “We were hung with bags, backpacks, and suitcases, like Christmas trees with decorations.” While rushing, the family lost a bag with half their money — 10,000 euros.

In another entry, Russian drag queen Ladochka joked about the challenges of sending sex toys through customs on a flight to the United Arab Emirates.

As time passed, the focus of these stories shifted to the longer-term struggles of adapting to new cultures, learning languages and finding schools for kids.

I Miy Leteli has become a source of comfort for many subscribers. A Russian migrant in Dublin thanked Masha K., a regular author on I Miy Leteli, for the “therapeutic effect” of her writings.

“Masha K.’s entries were incredibly apt, honest and ironic,” the Dublin subscriber wrote. “I still return to some of them when I feel alone.”

The founders of I Miy Leteli extended an invitation to friends still in Russia who are considering emigrating. They assured newcomers of support, sharing their experiences and knowledge gained in the past two years.

“If suddenly you think about leaving, know that we are waiting for you,” I Miy Leteli’s founders wrote after one year abroad.

“It was difficult for us, but we have already settled in a little. We opened schools in Montenegro and found good ones in Kazakhstan. We learned how to brew raf [a Russian coffee drink] in Israel. We have opened bookstores all over the world. We have created communities in all major cities. We know all the rules for transporting animals. We know how to fill out documents, bargain and swear in all languages. And we are ready to teach you this. It will be a little easier for you than for us. We will never call you Septemberists or other offensive words, no matter how much later you left than us,” they wrote.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.