Tomorrow is the last day of Shrovetide — the days of indulgence before the austerity of Lent. That means caviar, blinis, sour cream and a glass of vodka.

Far-sighted housewives stock up on food for the whole week. So what if there are blinis every day during Shrovetide? True, you need a bit of variety. But not to worry: you can surprise your guests at the holiday’s finale.

Not that long ago — just 150 years ago — black caviar in Russia might not have been cheap, but it was affordable. At the end of the 19th century in St. Petersburg it ranged in price from 1.80 to 3 rubles per pound, depending on the sort. At the same time, a pound of beef loin cost 70-80 kopeks per pound. The cost ratio of beef to caviar was at most 1 to 4.

Today, the price ratio of good beef to caviar is 1 to 40.

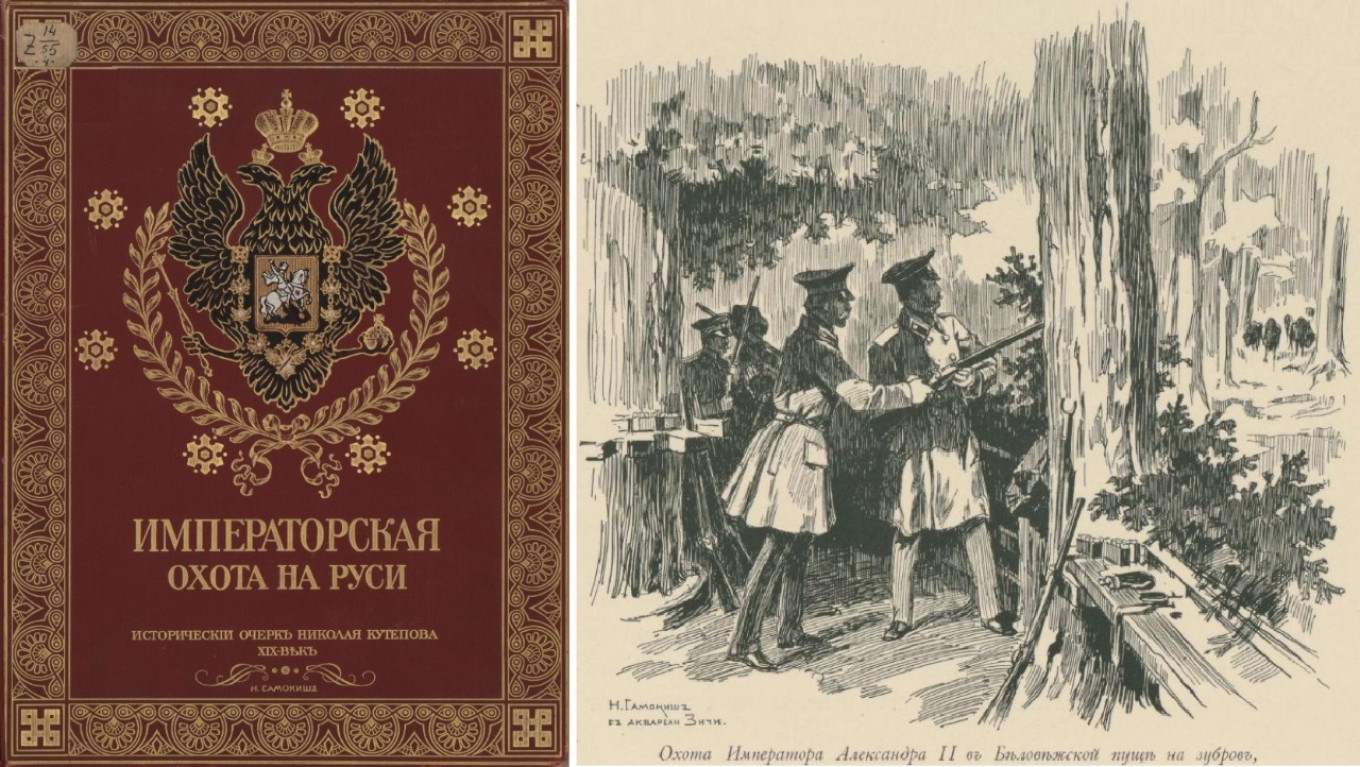

So for most Russians, blinis and black caviar are like stories about life long ago — for example, like a story in the book “Imperial Hunting in Russia,” written by Lieutenant General Nikolai Kutepov, head of the Imperial Hunt. He wrote this four-volume text over the course of 16 years by order of Emperor Alexander III. It’s a great source of information on the history of Russian hunting, as well as court and diplomatic history of Russia.

Among his tales is an unexpected story about blinis and caviar:

“I will describe a case I remember (unprecedented, I think, in the annals of royal dinners) with a German Prince. The hunt was conducted not far from Oranienbaum, and the dinner afterward was in the Oranienbaum Palace. I should mention that whenever there was hunting, and wherever breakfasts and lunches were held, all the food, meat, game, wines — basically everything — was brought in from St. Petersburg. The maître d' would know how many people would be there and would bring all the provisions necessary.

"At the dinner I’m telling you about there were blinis with caviar — and I have to admit that we always ate too much of them. The German Prince also liked the caviar very much, and he praised it to the man next to him at table, one of our Grand Dukes, who, as a hospitable Russian host, naturally offered him more. The Prince did not refuse.

"The Grand Duke turned to the waiter and ordered more blinis and caviar. They waited for two or three minutes, but the waiter didn’t return. The Grand Duke sent another waiter out with the order to serve the blinis and caviar immediately. Then the maitre d' arrived, embarrassed, and announced that alas, there was no more caviar. You should have seen the Grand Duke's embarrassment as he had to tell his dinner guest — eager for more caviar — that there wasn’t any left. Even the German was taken aback for a moment and then mumbled something about having had enough anyway. The maitre d' was fined. There was no question that it was his fault. Although he always took a particularly large supply of caviar, this time he failed to correctly estimate the appetite of the guests."

"When Emperor Alexander III, who was sitting on the left hand of the Prince, noticed some commotion and found out what the problem was, he too was displeased and and shot the maitre d' a look that scared him to death.

"Later to smooth over the gaffe at dinner, the Emperor ordered that two hunting dogs the Prince had admired be sent to him in Berlin."

Of course, Russians don’t live on black caviar alone. People think of blinis and red caviar as our traditional Shrovetide meal throughout history. But that can't be right. Today red caviar is from salmon caught from Siberia and the Far East. In 16th-century Russia, were they importing fish from the East?

Actually, in Russia “red caviar” means the caviar from the Far Eastern salmon family (which appeared in European Russia relatively late — only with the opening of the Trans-Siberian railroad in the early 20th century) as well as more common varieties such as the caviar of whitefish, pikeperch, perch and even smelt. That “red caviar” was known to Russians for many centuries. And it was far more widely eaten than black caviar from sterlet, sturgeon or beluga.

But what about trout, Baltic salmon (or more precisely the Baltic form of Atlantic salmon) which also produce red caviar? These fish could be found in the rivers of what are now the Baltic states, Karelia, and the White Sea. But we will hardly find any mention of this caviar until the 18th century.

There are several reasons for this. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the borders of Russia had just approached the Baltic Sea. The Novgorod Republic had been subordinated to the Moscow state only a few decades before. So, for example, in the “Domostroi” (1550s), the word “salmon” was never used with the word "caviar." You can only find “whitefish and black caviar.” This was the case in Moscow and Central Russia for a long time.

Another reason is that even in the 19th century, salmon caviar was considered unpalatable. “The caviar of whitefish and salmon in the northern basins (red caviar) found at local markets is not widely distributed,” noted the Russian ichthiologist Innokenty Kuznetsov in 1902. And traveler and journalist Vasily Nemirovich-Danchenko (the elder brother of the famous theatrical figure) wrote in his beautiful essay about the Kola Peninsula, “They [Loparians, Sami] only eat salmon caviar — large-grained and tasteless — as well as kumzha [trout] and bread.”

Until the 20th century, salmon caviar was only a regional dish of the North-West, and even then it was considered very niche and exotic. It was not appreciated at all in Central Russia.

The so called “red” caviar from pike, burbot, pikeperch, as well as from types of whitefish like round-nosed whitefish and European whiteish was a different story. This caviar was widely served at the Russian medieval table. It was prepared simply: it was put in a barrel, salted, and stirred. Easy to make, easy to store, and made from fish that could be caught just about everywhere, this “red” caviar was a product in high demand in medieval Russia.

And so, how you want to serve blinis at Shrovetide is up to you. We just give you a recipe for what we consider the best blinis for caviar or anything else: delicate, thin yeast blinis.

Thin Yeast Blinis

For 25 blinis

Ingredients

- 700 g (2 ¾ c) warm milk

- 300 g (1 ¼ c) warm water

- 1 tsp fast-acting yeast

- 450 g (15 5/6 oz or 2 c) flour

- 2 eggs

- 1 Tbsp sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- 2 Tbsp vegetable oil

Instructions

- Pour the warm milk (about 30°C / 85°F) into a bowl.

- Add the warm water (which should be the same temperature as the milk).

- Add eggs, salt, sugar. Stir with a whisk.

- In a large bowl big enough to contain all the blini dough, mix flour and yeast.

- Pour the milk mixture into the flour mixture in batches, stirring with a whisk after each addition. The batter will be runny, like for non-yeast blinis.

- Cover the bowl with clingfilm and put it in a warm place for 60 minutes.

- When the dough rises (since it’s liquid it won’t rise very much) and bubbles form on the surface, pour in the vegetable oil and stir. Leave for another 20 minutes.

- Stir again.

- Heat a frying pan until hot and grease with a piece of lard or vegetable oil.

- Use a ladle to pour onto the pan just enough batter as if you were making thin, non-yeast blinis. Fry over medium heat until browned on one side. Then turn the pancake over.

- Transfer the finished pancakes to a plate, brush generously with butter.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.