Today a journalist in Russia often does nothing more than rewrite press releases about enormous accomplishments and unparalleled successes. Back in the early 20th century, the profession of a journalist was both dangerous and difficult, too.

But reporters were not afraid to unearth and print stories that the authorities found unpleasant.

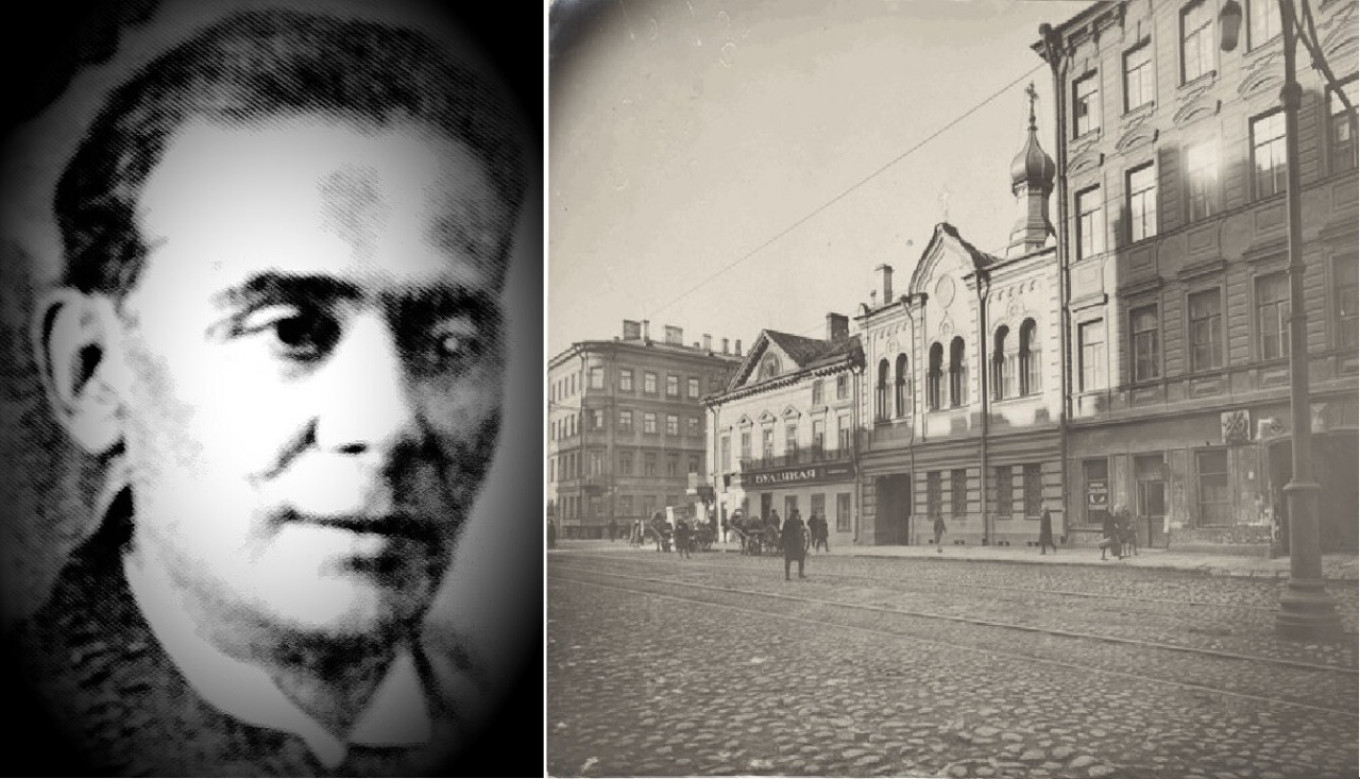

One of these journalists was “L. Lvov,” the pen name of Lev Klyachko, a man who led a fascinating life and was a real investigative journalist. Surprisingly, he managed to do it even in those years. Klyachko became famous for his article “Tactics of the Minister of the Sea” that cited facts about absolutely incredible embezzlement of funds during construction of battleships. He also published materials from the State Comptroller's office — information that was strictly secret. There was a quick reaction: “His Imperial Majesty addressed an edict to the Chairman of the Council of Ministers pointing out that this kind of disclosure of state documents to the press was completely intolerable.”

Klyachko was cut off from access to the ministries and put under surveillance. But this didn’t put a damper on his fervor. Another time he gave the newspaper information about a secret meeting of the two emperors, Nicholas II and Wilhelm II, that had been held on board the imperial yacht “Standard” while sailing around the Finnish islands. No one ever discovered how he got on the yacht.

After the February Revolution Lev Klyachko was one of the founders of the Committee of Journalists under the Provisional Government. Naturally, the Bolsheviks who came to power did not like him. He was arrested almost right away — in 1920. Only Maxim Gorky's personal appeal saved him from execution. After that Klyachko founded the publishing house “Rainbow,” which existed in Leningrad until 1930.

In 1926 he published his memoirs called “Behind the Scenes of the Old Regime” at his publishing house. We, of course, could not pass by a culinary theme. The nosy journalist seems to have received information from people who were very close to the court, and they told him all about the wife of Nicholas II.

“Until her last days,” writes Lev Klyachko, ”Alexandra Fyodorovna could not get used to the Russian court. Coming from an impoverished German family, she brought with her a purely German frugality, which she did not abandon even iwhen it concerned her relatives. Her father received annual grants from the king, for the repair of the family castle, for medical treatment, etc. She reduced the size of these grants herself.”

“Neither could she get used to the generosity of the Russian court. When she was presented with an estimate to support the House of Labor charity — a group she chaired — she was horrified by the annual sum of several hundred thousand rubles and flatly refused to approve it. The clever palace staff found a way around this. They began to submit a monthly estimate instead of an annual one. It passed.”

Until her last days she darned her children's stockings herself, which caused endless and often malicious ridicule and gossip. First the staff called her the “governess,” and then they began to call her the “cook.”

That’s what the staff called her below stairs. It all started with one incident.

The court cook was like a restaurant owner. For ordinary (not holiday) breakfasts he was paid 75 kopeks per person, and for lunches — 1 ruble per diner. Fruits and wines were separate and under the supervision of another person. The Tsarina would carefully check the bill so that the cook did not add a number of breakfasts and lunches that he did not serve.

Once the cook submitted a request to increase the cost of a breakfast to 1 ruble and a lunch to 1 ruble and 25 kopeks. He justified this by the rising costs of provisions. He got an increase. He got it, but first he had to endure a humiliating scene. The Tsarina summoned him and, in the presence of the maid of honor Golenishcheva-Kutuzova and Count Lamzdorff, she scolded him fiercely and insisted on keeping the same rate. She called him a swindler and used other words unsuitable for royal lips. The courtiers, who had calmly reacted to Alexandra's tight purse strings, could not accept this kind of “bourgeois” behavior and began to call her the “cook.”

To be fair to the thrifty Tsarina, it should be said that the breakfasts of the royal family were really not luxurious at all. The last Russian Emperor preferred simple dishes. For breakfast they had a special tray of butter and different kinds of bread (sweet bread, rye and muffins).

There was always ham, boiled eggs and bacon that could be requested at any time. Then kalachi — a traditional round Russian bread — were served. This was a tradition established for centuries at court and maintained by the Empress.

The Emperor also ate porridge, especially his favorite —Dragomirov porridge. This dish is still a bit of a a mystery. No one knows who invented it or who introduced it to the last Russian Emperor. It was named after a Russian general and military instructor, Mikhail Ivanovich Dragomirov. This porridge was served on the tsar's table almost every day. And it was just buckwheat groats with mushrooms. True, the recipe had a few secrets. First, the porridge was cooked in cream. Second, it was served in layers, like a pie. And third, a sauce made of wild forest mushrooms was a key ingredient. So although the ingredients were not expensive, the porridge had a very rich and elegant appearance.

Just as a century ago, sooner or later every host or hostess thinks about how to make an impressive yet inexpensive dish for the family or guests. Of course, the concept of “inexpensive” for the royal table of the early 20th century and the usual diet of a modern family are not always in sync, to say the least. But still, it’s possible to give guests a bit of a surprise using the simplest ingredients. And that’s what we do, for example, in one of our favorite appetizers.

Garlicky Cheese Stuffed Peppers

Ingredients

- 3 sweet peppers of different colors

- 250 g (scant 9 oz) bryndza (or feta)

- 150 g (1 c or 8.8 oz) chilled butter

- 2-3 garlic cloves

- 1 Tbsp mayonnaise

- Dill

Instructions

- Trim off the stalks of the peppers and remove the core.

- Grate the cheese and butter on a fine grater.

- Press the garlic and finely chop the dill.

- Mix everything thoroughly, pack the filling tightly into the peppers and put them in the refrigerator for two hours.

- Use a sharp knife to cut the peppers into circles half a centimeter (1/4 inch) thick and arrange nicely on a dish.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.