The Trump administration’s abrupt freeze on foreign aid has plunged exiled Russian NGOs and media outlets into uncertainty, jeopardizing their funding and posing what some are describing as the greatest challenge to Russian civil society since the Kremlin enacted its “undesirable” organization law a decade ago.

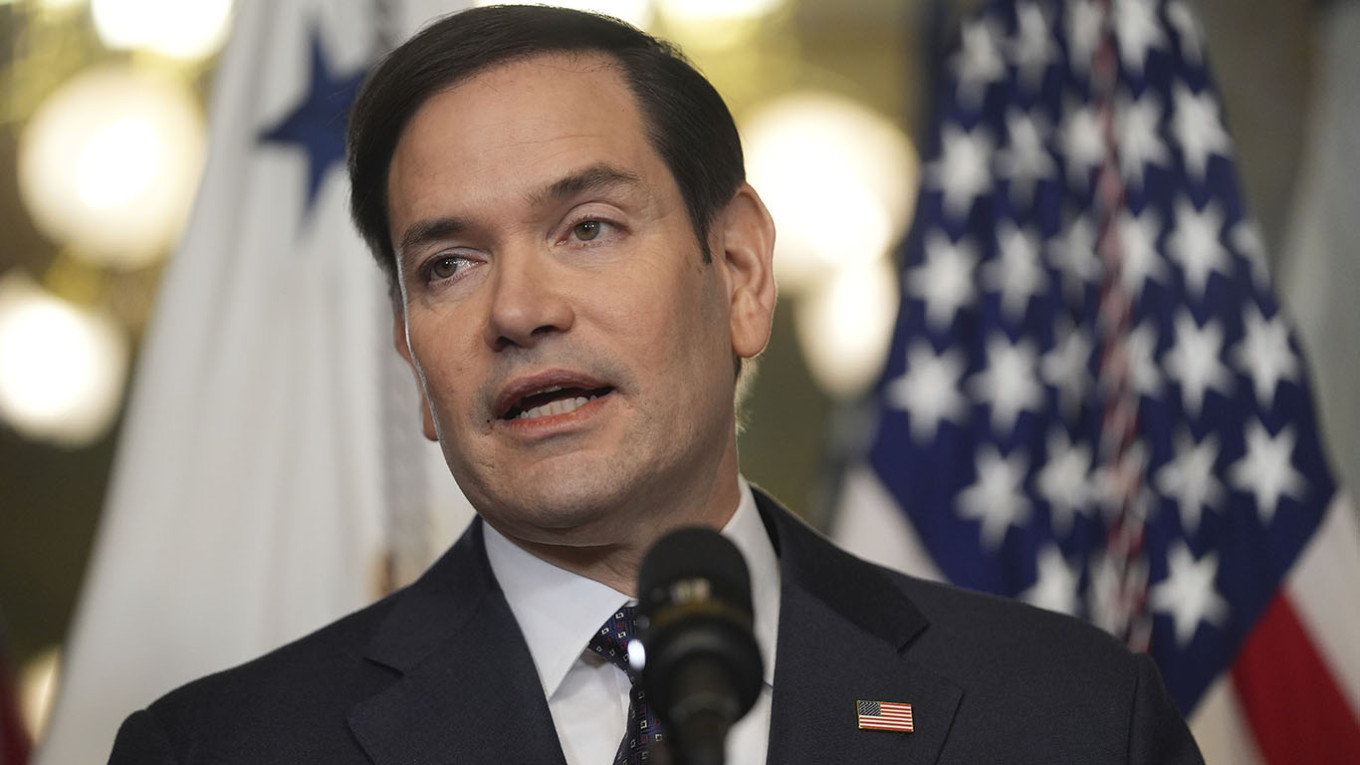

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio issued a sweeping directive last Friday, pausing all foreign aid for 90 days. The move aims to give the Trump administration time to review which programs align with the president’s “America First” agenda and determine which should continue receiving U.S. funding. Organizations have been issued stop-work notices on existing projects, along with a suspension of further disbursements.

The freeze has affected a broad range of initiatives, from landmine removal efforts in Iraq and HIV/AIDS treatment programs in Zimbabwe to typhoon emergency relief in the Philippines and wartime civilian programs in Ukraine. While Rubio later granted a waiver for “life-saving humanitarian assistance,” the vague wording has only deepened confusion, leaving organizations scrambling to determine whether their work qualifies.

For Russian NGOs and independent media operating in exile, many of which cannot generate revenue from donations or advertising inside Russia due to their designation as “foreign agents” or “undesirable organizations,” the sudden cutoff of U.S. funding is potentially devastating.

“This is the biggest funding crisis for Russian civil society since 2015, when Russia’s law on ‘undesirable foreign organizations’ caused several Western private foundations to shut down their Russia programs,” a Washington, D.C.-based source familiar with U.S. government funding for Russian organizations told The Moscow Times.

The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity, estimated that as many as 90 organizations could be affected. While some receive funding from private donors and European governments, many are losing a significant share of their budgets due to the Trump administration’s freeze.

“The consequences will vary by organization, depending on their financial situation and alternative funding sources,” the source said. “But most will at minimum have to scale back operations and lay off staff. Some of the largest and most prominent independent Russian media outlets and civil society groups could be forced to shut down entirely.”

Kovcheg (The Ark), an exiled nonprofit that provides support to anti-war Russians both abroad and inside Russia, said it was notified earlier this week by U.S. donors that some of its funding had been paused due to the State Department directive.

“We’re still in a better situation than most NGOs because we cover half of our budget through crowdfunding, but still, I need to cut a team and [some of] our activities,” Anastasia Burakova, who heads Kovcheg, told The Moscow Times.

Burakova added that donor organizations she had spoken with seemed uncertain about what would happen next. “They don’t have a clear idea of whether the programs will continue after the audit or which areas the new administration will support,” she said.

Almut Rochowanski, a nonprofit consultant with years of experience working with Russian human rights activists, recalled a similar “existential panic” that followed Russia’s 2012 “foreign agent” law in the context of the current funding freeze.

“It was revealing. It showed that access to foreign money was seen as the single most decisive factor for their continued work and existence,” Rochowanski told The Moscow Times.

A journalist who founded an independent Russian news outlet now operating in exile described the “emotional rollercoaster” he and his team experienced upon learning that a “significant portion” of their funding had been frozen this week.

“It’s not like we were entirely dependent on American grants… It just so happened that at this moment, we were more reliant on U.S. funding, and everything hit at once,” the journalist said on condition of anonymity to discuss internal matters. “Almost overnight, the [money] was frozen.”

Despite the setback, he said his team would “keep fighting” and look for alternative funding sources. “If not, we’ll have to close, because, at this point, there’s simply nothing left to pay people with,” he added.

Some Russian organizations noted that while they do not rely directly on U.S. funding, they receive grants through intermediaries that do — causing the freeze’s effects to spill over to them.

“Some of the donors where you didn’t know who their source was… turned out to be one way or another linked to the same basket,” the head of a Russian nonprofit operating in exile said, requesting anonymity.

“Our donors told us to wait. They say they don’t know how long the pause will be,” the nonprofit head added. “So everything is on hold.”

Given the sweeping nature of the State Department directive, Russian independent media and NGOs are far from the only ones in the region to be impacted.

Ukrainian newspapers receiving funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have also said they were forced to suspend ongoing projects as a result.

And in an opinion column this week, The Kyiv Independent’s Chief Editor Olga Rudenko described how the U.S. funding freeze had left programs — including humanitarian relief, mental health support, media initiatives and community development projects — without critical financial backing.

Most Russian organizations contacted by The Moscow Times declined to comment on the freeze’s impact, with some stating they were still assessing how it would affect their operations.

“Russian media outfits probably understand that openly flaunting the fact that they are funded by Western governments might alienate their audiences,” Rochowanski said, pointing out that even anti-Kremlin Russians do not always view the West as a benign actor.

“They may also want to be careful because drawing unwanted attention from the Russian authorities could lead to threats against their reporters and sources,” she added. “For those same reasons, Ukrainian media can be quite open about how they are funded by Western governments.”

With U.S. funding on hold, some organizations are turning to European institutions for support, with discussions of potential emergency funding underway, according to the Washington, D.C.-based source.

The European Federation of Journalists urged potential European donors to step in and fill the gap left by the withdrawal of U.S. funding. While it did not specifically mention Russian organizations, the federation emphasized the reliance of Ukrainian news publications and exiled Belarusian media on U.S. financial assistance.

Still, even if civil society organizations manage to secure stopgap funding during the three-month freeze, there is growing concern that if the Trump administration’s review leads to long-term cuts, many will not survive.

“In the long term, if U.S. government funding isn’t restored, Russia’s independent civil society as a whole will be greatly diminished,” the Washington, D.C.-based source warned.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.