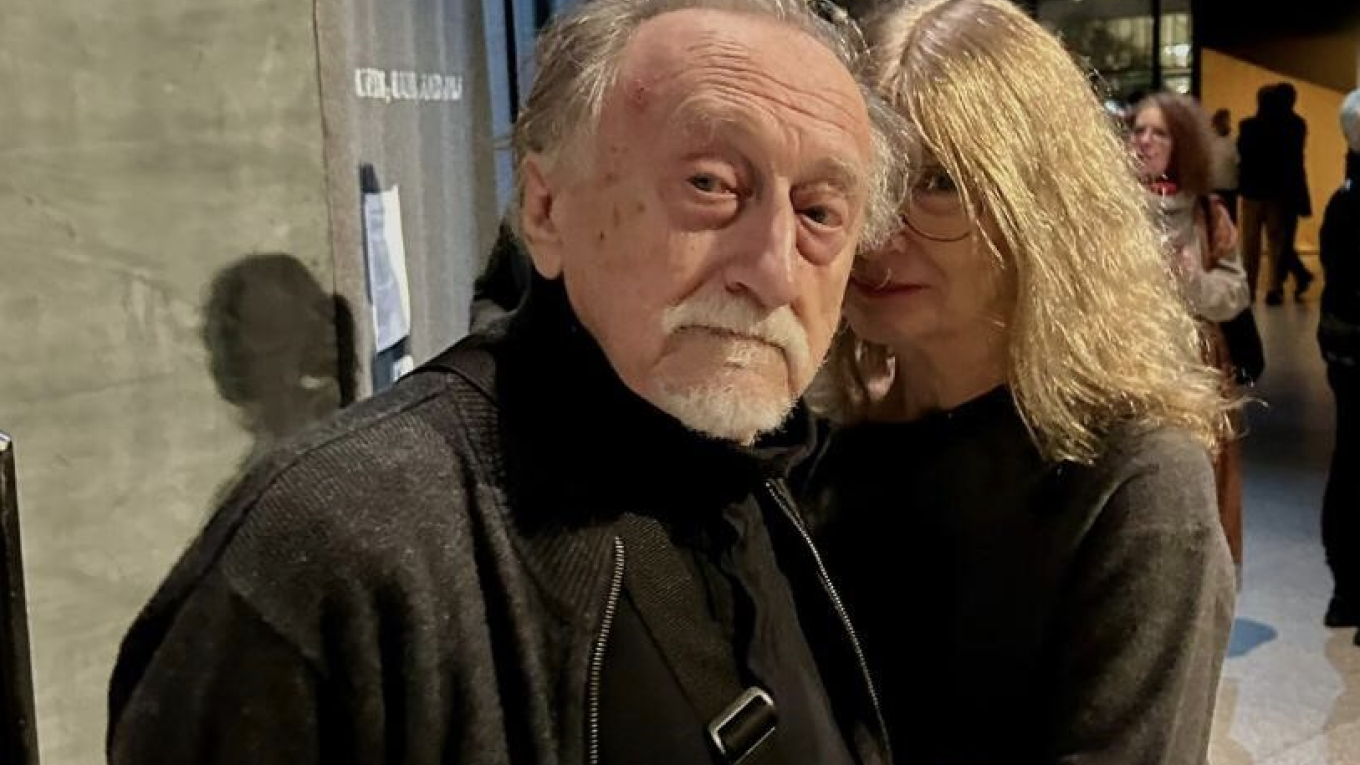

Renowned Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov is currently exhibiting his work at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York.

“Refracted Times,” a retrospective of his career running until Feb. 22, 2025, includes early pieces like the slideshow “Yesterday’s Sandwich” and his latest video work, “Our Time is Our Burden” (2024).

Mikhailov and his wife and creative partner, Vita, spoke to The Moscow Times about the exhibition, their artistic process and the evolving themes in his photography.

Andrei Muchnik: Does the exhibition have a specific concept, or was it influenced by the availability of photographs?

Vita Mikhailova: It’s a deliberate decision. There’s the very first work, ‘Yesterday’s Sandwich,’ and the most recent, ‘Our Time is Our Burden,’ and everything in between — that’s essentially how a retrospective is built. And, of course, the space dictates some of it. When it’s a gallery — there’s only so much that we can show.

At the same time, it also depends on the moment — time dictates what is appropriate to showcase right now and what no longer feels relevant. Not that it doesn’t work anymore, but simply that we don’t feel like addressing it at this moment.

AM: Why these series?

Vita: Probably because right now we’re talking more about Ukraine. That’s why the series ‘By the Ground,’ created in 1991, is featured — it’s truly the first series made in Ukraine, marking the end of the Soviet Union and the beginning of Ukraine. ‘At Dusk’ was shot in the 1990s.

And ‘Salt Lake’ is truly from the late Soviet era, 1986. It’s about Sloviansk — the region currently at the center of our deepest anxieties.

Boris Mikhailov: My name — Boris Mikhailov — is itself associated with the end of the Soviet era.

Vita: He documented, like a chronicler, capturing the Soviet era and the worldview of the Soviet individual.

AM: Where do you currently live?

Vita: We live in Berlin. And all our children have now relocated from Kharkiv to Berlin as well.

AM: Before the war, as I understand, you traveled to Ukraine and worked there quite often, right?

Vita: Yes, we never really thought of real emigration. We still have Ukrainian passports, and it just worked out that we traveled back and forth. But not anymore.

AM: Do you consider yourself a Ukrainian artist, a post-Soviet artist? Or maybe international or German?

Boris: It’s hard to say. Probably a Soviet underground artist.

AM: Since we’re talking about the Soviet underground, can you tell me about your connection to Moscow conceptualism?

Boris: I knew Vladimir Yankilevsky, Erik Bulatov, and Ilya Kabakov — though I knew Bulatov less. But my relationship with Kabakov was particularly close. He encouraged me to explore ideas of what could be done. He pushed me to approach things as if observing from above.

From Kabakov, I also learned the importance of connecting with text. I was already working with text, but it wasn’t as emphasized. My acquaintance with him encouraged me to give text a larger role, which, of course, was one of the key elements of contemporary art at the time.

AM: Tell me about your creative process — how do your new series come to life?

Vita: I think we need to start not with the new series but with the older ones.

Boris is an old-school photographer who always carries a camera. Nowadays, everyone has a phone, but he was the person who always had a camera with him. When one series ends, the search for the next begins. Every day, he prints test shots at home, but only when one particular image stands out does it draw his attention.

And then, when you're out on the street, you start to see how everything layers onto that initial impression, and that’s how it comes together.

New series also come together based on some internal feeling. There’s a constant process of shooting. It’s a kind of process of assembling and combining things — shaped by how you feel — and then the sequence starts to take form.

Boris: I try to capture, on one hand, the atmosphere, and on the other hand, that atmosphere aligns with a certain title.

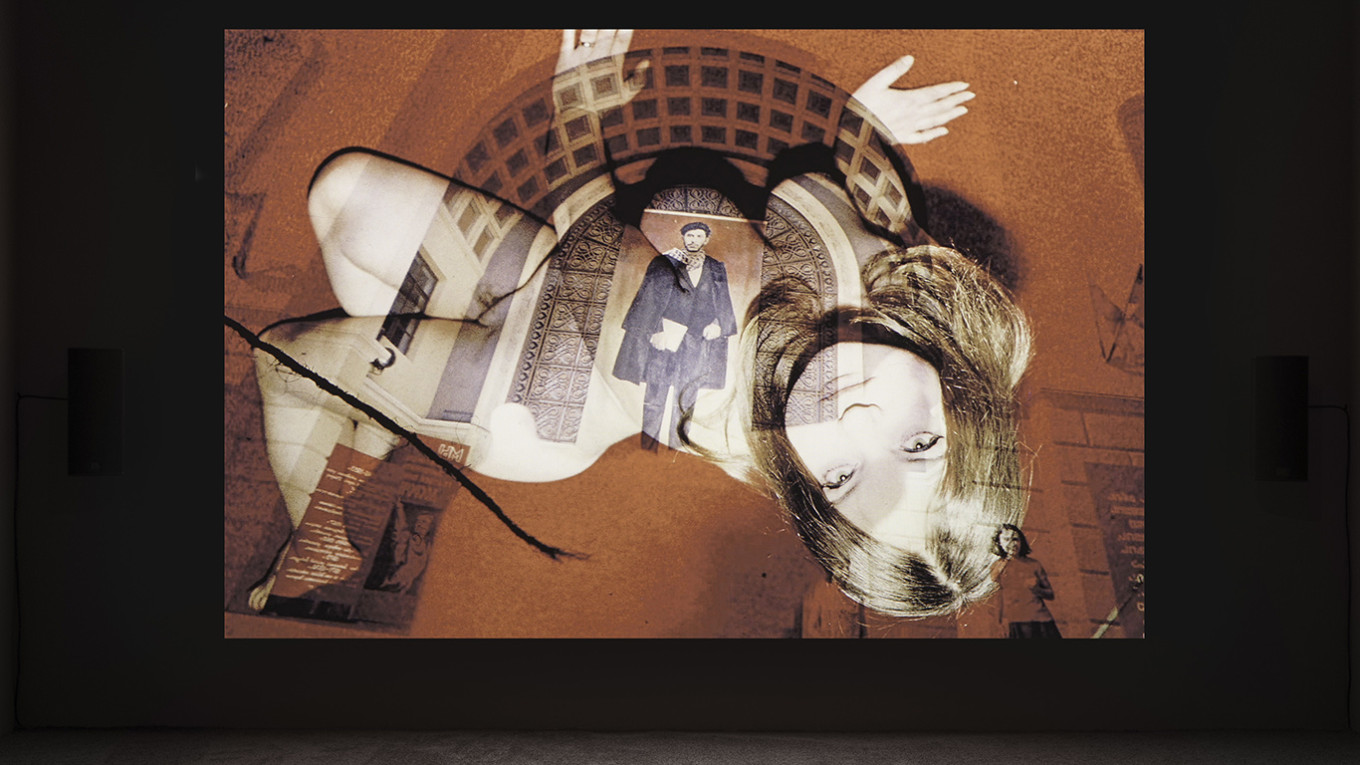

Vita: Boris’ last work, ‘Our Time is Our Burden,’ consists of three parts. The first was shot back in 2019. At the time, there was this sense of unease, this anxiety, like it was foretelling something. Then came the second part, created when there was still a sense that maybe, just maybe, there was a chance of escaping death. The third part is already about the war — it’s 2023, and by then, we’re feeling the full impact of what it’s like.

Boris: These are diptychs; that’s the method I’m using now. Capturing war without war itself can only happen through understanding. You’re just walking down the street, and suddenly, you might come across something. These are situations without war, but they somehow remind me of war or evoke thoughts connected to it. I shot most of this in Berlin.

AM: And the photographs from Ukraine — are they just news footage?

Boris: Yes, from the TV, from TikTok.

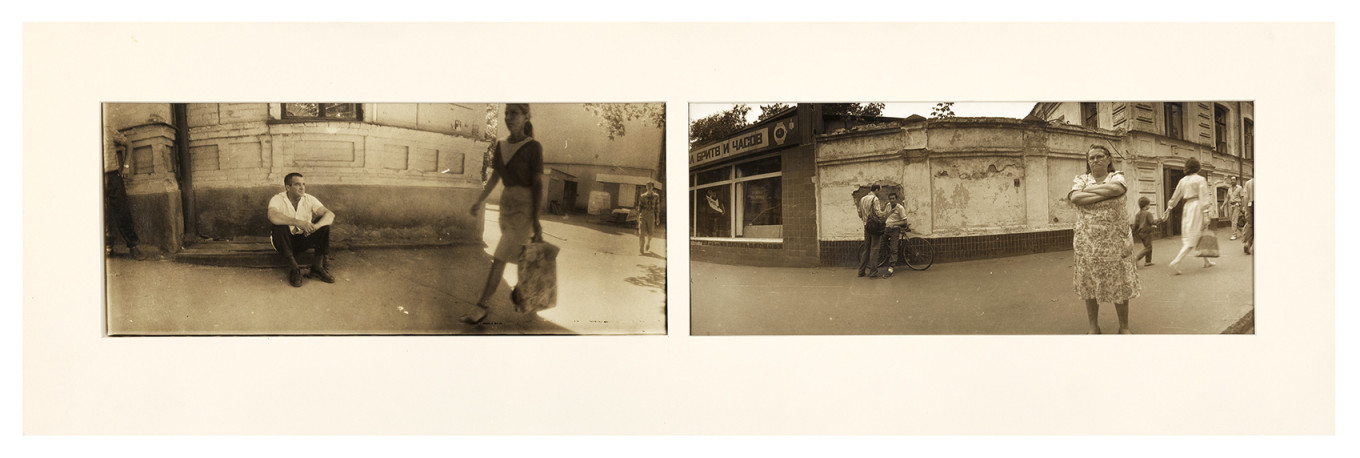

AM: What about your first work — ‘Yesterday’s Sandwich’ — did you originally plan this as a slideshow, or were they intended as individual photographs?

Boris: These are all accidental things, captured unintentionally and then assembled together. The idea here is about transitioning from the mechanical to the semantic level. Two slides placed within a single frame represent a new technological discovery. The key was to find these combinations. And these combinations, in a way, are something new — combinations that didn’t exist in cinema before.

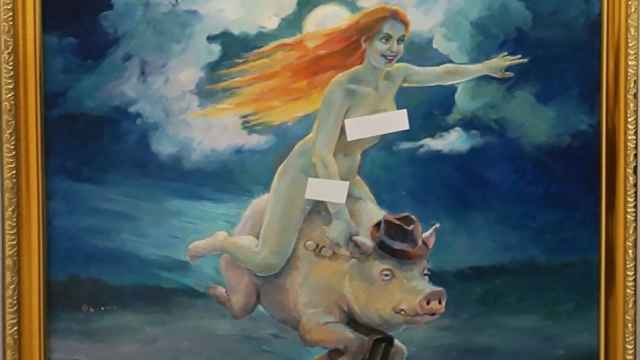

It’s kitsch, a reaction against the authorities; the only way to stick it to the authorities was by creating kitsch.

AM: The slideshow uses a soundtrack from Pink Floyd's ‘Dark Side of the Moon.’ Why this album? Were the photographs taken around the same time you were listening to it?

Boris: The photographs were taken a little earlier, but it was almost the same period.

AM: And ‘Salt Lake,’ what’s happening there?

It’s Sloviansk, in the Donetsk region. It’s warm soda water coming out of a pipe, and people bathe in it, it’s supposed to have healing qualities. It’s the Ukrainian Ganges.

It’s quite safe; my father used to swim there. In the photos you see a kind of a sea resort situation, although it’s no sea resort. It’s this game of being ‘in-between.’

AM: Why is the 1991 series called ‘By the Ground’?

It was shot from below, as if through the eyes of an old woman walking, close to the ground.

This was the beginning of the country’s [the U.S.S.R.’s] collapse. It was the collapse of the entire country — not just an ideological collapse, but the collapse of architecture, of buildings, of everything.

At that moment, most people gained a kind of freedom, but along with it came an economic blow. This series already has a certain conceptualism, which is reflected in its use of color. First of all, everything became browner. Visually, it feels like we’ve descended into the past. This was in Kharkiv, but it could have been any city.

AM: And ‘At Dusk’ series — that’s also Kharkiv?

Boris: Yes, the photographs were taken in Kharkiv in the 1990s. It's my association with war. I know it, I still remember it. It’s that powerful feeling I had when there was just a month left before the Germans arrived in Kharkiv, less than a week, and we had to leave for Kirov. I remember the intense anxiety my mother felt and the airplanes flying under the searchlights.

AM: Vita, what role do you play in tandem?

Vita: I don’t really want to answer that. (smiles)

Boris: The homeless series [‘Case History,’ one of Mikhailov’s most famous series, first shown in the late 1990s] wouldn’t be possible without Vita. We basically made that series together.

Vita: We just talk about photography 24/7, that’s what my role is.

Boris: Vita knows where everything is and takes care of everything — she’s an institution in herself.

She has connections and a deep understanding of both the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. This allows her to find and present what hasn’t been shown before, creating something new while continuing the same path.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.