The Twelve Days of Christmas (Christmastide) — the most joyful and mysterious season of the year — is coming to an end. In Russia the period from Christmas to Epiphany was called Saints' Days, or Holy Evenings. But despite the religious names, the days were filled with fortune-telling, singing songs and casting good-luck spells.

These twelve days have always been problematic for the Russian authorities. On the one hand, people are just having fun and drinking a bit. On the other hand, it was not very Orthodox, not at all religious. In fact, it seemed a bit pagan. And on the third hand, doing nothing but having fun for almost two weeks seemed just plain wrong. Why were they having such a good time at our expense?

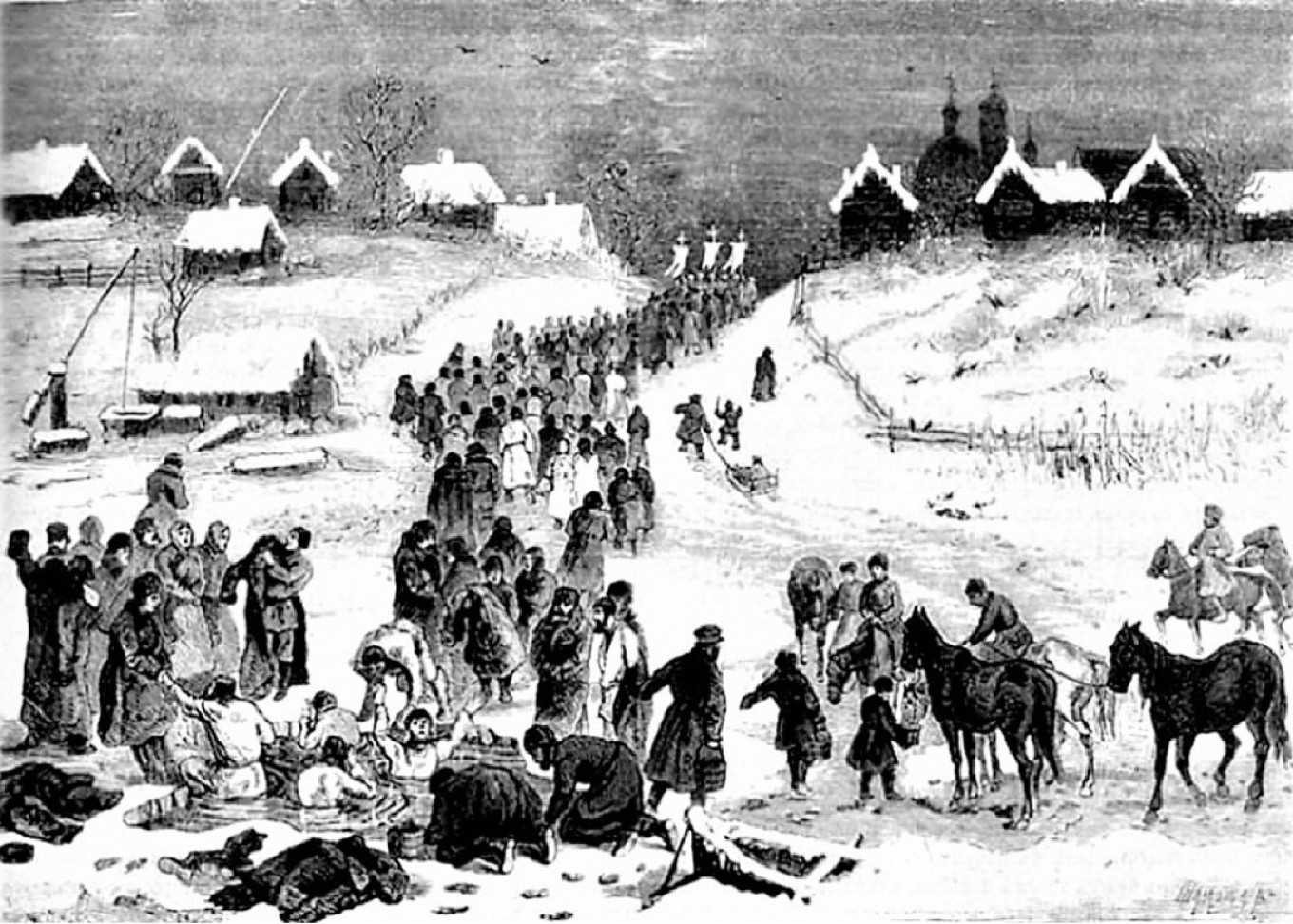

As the Russian historian Euplus Solovyev noted in his book published in 1877, "Christmastide Among the Merchants and Petty Bourgeois of Kazan," doing any work but essential chores around the house during this period was considered a sin. People visited each other, sang songs, and strolled around in village in large groups. When they arrived at a house, they’d be invited in to sit down at the table. The hostess would bring out all the dishes she had baked, boiled and fried that morning. One guest carved the meat; the rest grabbed pieces with their hands. There were no forks. A towel was stretched across everyone’s knees for the guests to wipe their hands on.

If there was vodka, the host served the guests in shot glasses. Beer was drunk from a large tureen that was passed around in a circle. After finishing breakfast or lunch, the guests would stand up, say a prayer to God, thank the host for his hospitality and go on to the next house, where it started all over again.

“An inordinate amount of food is eaten over the holidays, which rarely went by without some fistfights among the men. The girls have their own fun when they get together, always in the evening by the light of a candle or a bit of kindling. They’d play games, dance and tell fortunes — all of it was pure superstition.”

Remember the classic poem by Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852), the great poet Alexander Pushkin’s closest friend? “On the evening of Epiphany, girls try to tell their fate; they’d take off a boot and toss it over the gate.” The young man who'd pick up the boot and bring it to the door was the girl’s intended.

Omens were very important during this time. If your left eye itches, something good will happen; if the right eye itches, you’re in for trouble. If the palm of your right hand itches, it means you’ll have to hand over money. But if the palm of your left hand itches, you’ll be receiving some cash. And if the bridge of your nose itches, it means that someone in your family has died.

The authorities took a dim view of all this holiday nonsense. As the Russian historian Ivan Golikov, author of the book “The Acts of Peter the Great,” wrote in 1789, “the monarch could not stand Christmastide, which kept people from their posts and jobs.” The holiday season was a time of idleness, silly games and drunkenness.

“The Great Sovereign, who was an enemy of idleness, prejudice and pride, observed the same customs but to mock, not celebrate. He dressed the most self-important boyars in richly decorated ancient robes and took them to noble houses. Following the old traditions, the noblemen wished them long lives and plied them with strong drink. In this way they made fun of the boyars’ pride and humiliated them while treating the common people with more affection and indulgence. Celebrating this way became something shameful.”

Epiphany, which comes at the end of Christmastide on Jan. 19, is one of the main Orthodox holidays. For a long time it coincided with Christmas and was called the Manifestation of Christ. Epiphany became a separate holiday in the 9th century. But Christmas Eve and the Eve of Epiphany have the same name in Russian: сочельник (sochelnik).

The blessing of water is one of the central and most memorable traditions on this day. According to ancient belief, this water will remain pure until the next year. Believers sprinkle it around their homes and on their children to protect them from sorrows and troubles. But today the priests warn that the water remains pure only if the person has “a reverent attitude.”

In other words, if you were poisoned by “holy” water from the river, it means that you have little faith.

As for food, there is no fasting on Epiphany. But people keep strict fasts on the Eve of Epiphany. And just as on Christmas Eve, the recommended dish here is a porridge made of grains (wheat, rice), honey and raisins called сочиво (sochivo) — for which the day is called сочельник (sochelnik). Since ancient times the Eve of Epiphany was not as much fun as the other winter holidays. This is no wonder: it’s hard to be merry when you are observing a strict fast.

But on Epiphany a lavish table was set with all the variety of dishes not permitted during a fast. Each house laid out a feast of meat soups, dumplings, roasted meat and poultry. They baked pork and beef, fried giblets with onions, turnips, and later with potatoes. Of course, the holiday table included fish. When there were so many filling appetizers, it was no sin to drink vodka and other fruit liquors.

At the end of the meal there were, as always, all kinds of fancy, light and delicious baked goods. The hostesses baked everything: elaborate karavai breads, blinis, angel wings and gingerbread. The sweet dishes were usually filled with jam, honey, nuts and dried fruits.

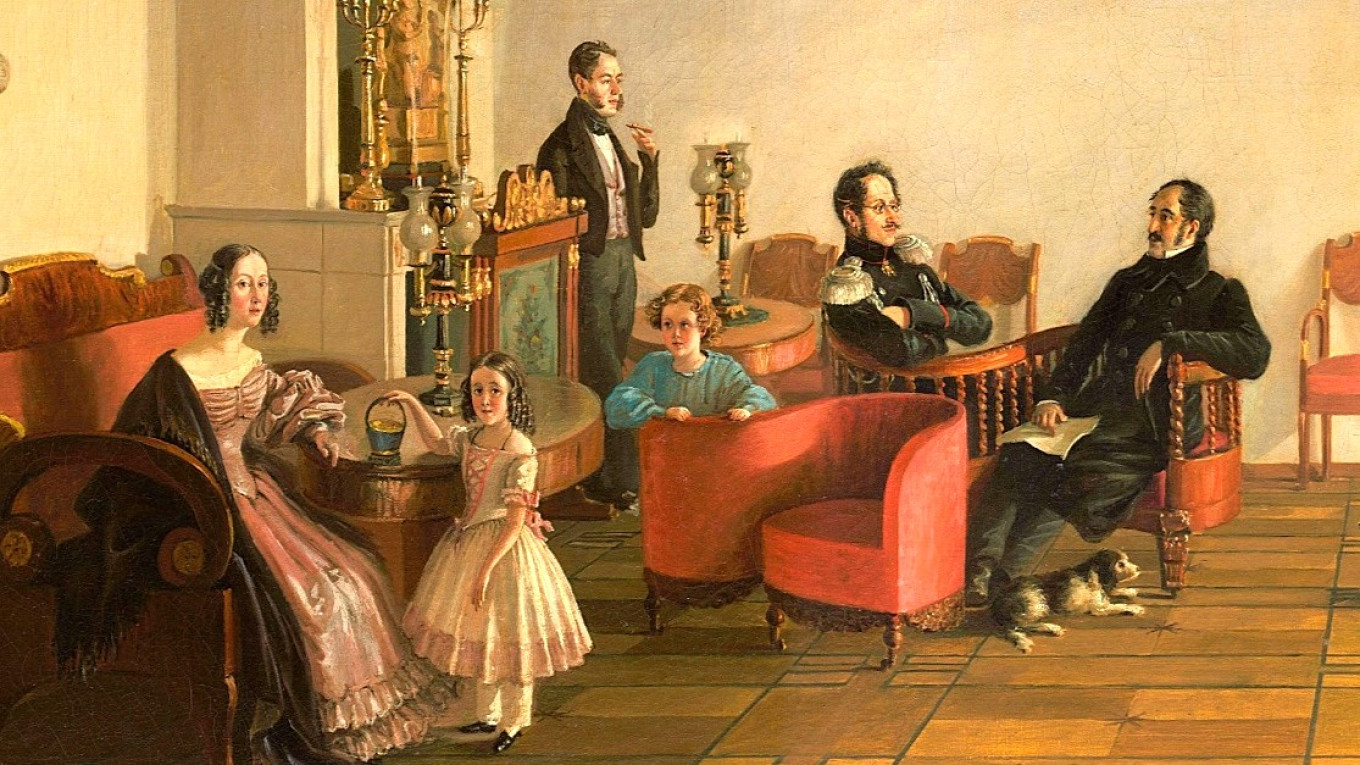

But what about Pushkin? He is not only a figure in Russian letters, but also in Russian cuisine. A man of his times, he loved both simple village dishes and elaborate concoctions from the best St. Petersburg restaurants.

“I loved to dine at the Pushkins’ house,” recalled lady-in-waiting Alexandra Smirnova-Rosset. “Imagine buckwheat blinis, then filled with chopped boiled eggs, then grainy blinis with snets, then grainy pink ones. I have no idea about the pink ones. How did they make them pink? With beets. Pushkin could eat 30 of them, sipping some water after each one, and he never experienced the slightest indigestion. Alexander Sergeevich really loved these special blinis made with beet juice.”

Beet blinis can be served with white gooseberry jam, which according to the memories of A. Smirnova-Rosset, was always on the great poet’s table. Or simply with honey.

Beet Blinis

Ingredients

- 1 small beet (200-250 g/7-9 oz)

- 500 ml (2 c + 2 Tbsp) kefir

- 250 g (2 c) flour

- 2 eggs

- 5 Tbsp sugar

- 1/4 tsp of salt

- 1/5 tsp citric acid

- 1/2 tsp baking soda

- butter for serving

Instructions

- Roast the beets, cool and grate them finely on a grater or in a blender.

- In a saucepan, heat the kefir with the sugar, salt and citric acid, bringing the mixture to a temperature of about 40°C /104°F.

- Lightly beat the eggs.

- Pour all the flour in a large bowl. Pour in half the kefir and mix well. Add the eggs and beets.

- Add the remaining kefir little by little. The batter should have the consistency of liquid sour cream.

- Mix thoroughly and pour in the baking soda.

- Gently stir the batter. Carefully dip in the ladle and fill with batter. When not using, do not submerge the ladle in the batter, but hang it over the rim of the bowl.

- Pour the batter on a heated frying pan greased with a piece of lard. Flip.

- Butter both sides of the blinis generously. Serve with honey.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.