In 2024, almost three years into the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian artists who left their homeland for political reasons have been working under the weight of practical constraints. They have had to find new galleries and buyers, worked with limited funding while juggling a second job or family life, squeezing their work into makeshift exhibition spaces.

But for artists now settled in Berlin, London, or Belgrade, there were deeper concerns. Did they still have an audience? Did they still have something to say?

In the best shows of the year, the answer was “yes.”

This is not to say that the artists weren’t frustrated. Nadya Raplya, a Moscow artist now in Berlin, told The Moscow Times in December: “When I was in Russia, I felt that I was doing something brave, something significant. But in Europe, I felt as if I was just posing. I left, and I'm shouting from afar: ‘You guys in Russia are assholes’.”

Raplya’s best-known work is a blank canvas emblazoned with the phrase “A pozdno, blyat’, risovat’” — ‘It’s too f***ing late to draw.’

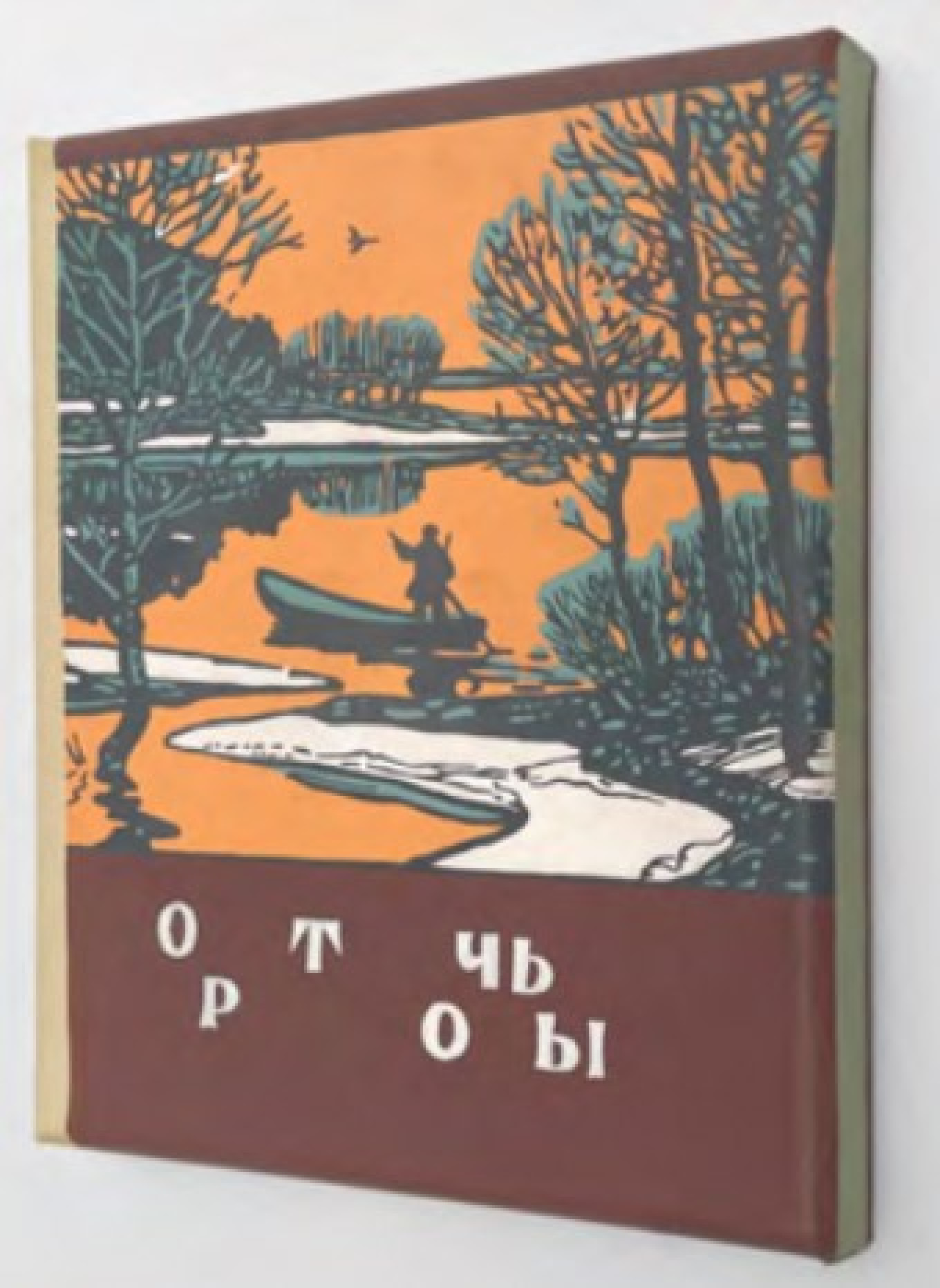

In the summer of 2024, London’s Pushkin House exhibition space hosted painter Darya Irincheeva, who also explored the “blankness” of forced censorship. As part of an ongoing series of oil paintings, Irincheeva’s show, “Forced Omission” recreated covers of books written by authors, poets, scientists and engineers in the former Soviet Union who had been political prisoners, omitting some letters of the titles to indicate the authors’ disappearance while in the gulag.

The author plans to recreate over 700 covers to shine a spotlight on the great irony of the time: the golden age of Soviet graphic design was also the era of the greatest political cruelty.

There were times when the need to be imaginative with venues became integral to new works of art. In another landmark show, artist Pavel Otdelnov took over the Old Waiting Room at London’s Peckham Rye train station, which he called “the venue of my dreams … an eternal waiting place amidst bustling streets.”

The waiting room was home to Otdelnov’s installation “Hometown” for a week in June. Across 24 ghostly canvases, the painter explored his relationship with Dzerzhinsk, a military-industrial center about 350 miles northeast of Moscow where he and his family lived for generations. He divided the space into areas representing the themes of environmental catastrophe, weapons production, gangs, and his family history.

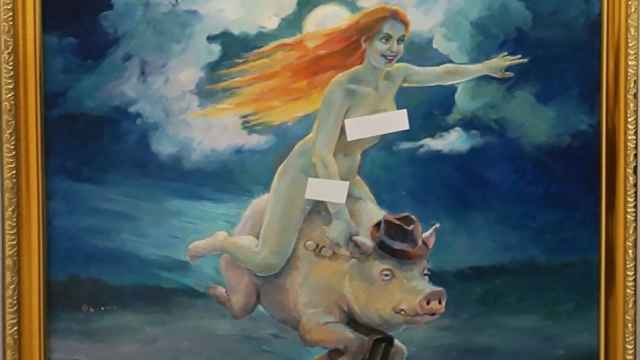

In August, The Moscow Times brought together over 100 works by Russian-speaking artists opposing war and authoritarianism in a month-long show called “Artists Against the Kremlin” at Amsterdam’s De Balie Arts Center.

All the art expressed some form of protest or political disillusionment. Yet the styles and media on display were diverse: sculpture, painting, video and soundscapes, and even ceramics. For example, Masha Bolotina repurposed a Soviet recruitment poster in a comment on the suicidal nature of Russia’s war. She painted a saluting soldier about to shoot himself, under the slogan: “Be Prepared!” The artist who goes by olo.olooloolo [Vlad Ogay] decorated a bishop’s miter with intricate and obscene prison tattoos.

The exhibition attracted some big names, such as Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova and political prisoner Sasha Skochilenko. Skochilenko’s budding career was cut short when she was imprisoned for replacing supermarket price tags with anti-war slogans. The young illustrator’s release as part of this year’s historic prison swap was a moment of celebration for Russian exiles.

The Russian diaspora is anything but a unified group. While some Russian-born creatives are still commenting on domestic politics from afar, others are immersing themselves in new cultures, or exploring broader, existential themes in their new projects. For example, this year, Andrei Blokhin and Georgy Kuznetsov, the two halves of artist-duo “Recycle Group,” contributed to the exhibition “Parallel Worlds” at Gazelli Art House, Baku, in November. The pair use mixed-media and generative technology to explore the idea of utopia — and humanity’s growing dependence on AI.

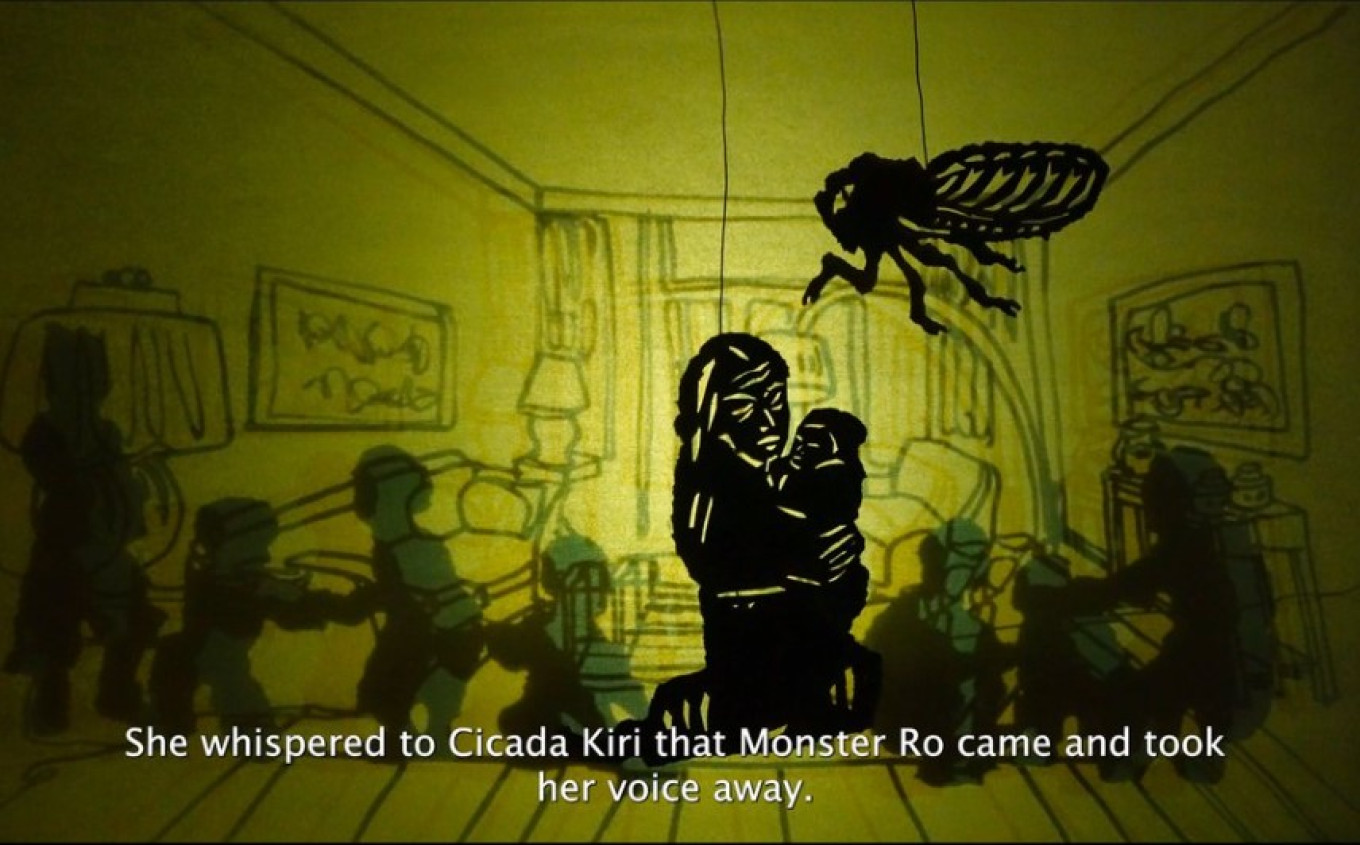

Artist Katya Muromtseva completed a residency in Japan, using shadow puppets and film to dive deeply into local folklore. Last year The Moscow Times covered Katya Muromsteva’s solo exhibition “Women in Black against the War.” This year the artist took a step away from the themes of protest and completed a residency in Japan, using shadow puppets to create a series of animations that draw on Japanese stories. The two films, “Whistling Mountains” and “Monkey Tales,” make poetic use of traditional techniques and can be seen here.

For many of Russia’s exiled artists, 2024 was a year of innovation. Group shows like “Artists Against the Kremlin” gave artists — and audiences — moments of solidarity. But other work created this year reflects the reality that many artists now work alone, in very different countries, and are accepting that they may never return home.

Nadya Raplya said she would “return to Moscow tomorrow if Putin died,” but she added: “I’m in the process of accepting that it may never happen. It’s hard to live in uncertainty for so long.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.