Chocolate appeared in Russia in the 18th century. It first came as a drink, made fashionable by Francisco de Miranda — a revolutionary, officer and passionate supporter of the independence of the Spanish colonies in Latin America.

It is said that Catherine II and Prince Grigory Potemkin became great connoisseurs of the new drink. However, at that time only the wealthy could afford this sweet concoction.

But when solid chocolate appeared in the Russian Empire 150 years ago, even poor people could afford it. In a very short period of time confectionery factories mastered mass production of this sweet in the most intricate forms. For example, the Moscow factory of the merchant Johann Ding produced chocolate eggs in dozens of sizes. Products # 1-32 were sold with pictures and little toys inside, while the largest eggs had no filling — but their size made a huge impression.

Above: A collection of chocolate eggs from the beginning of the 20th century, the ancestors of Kinder Surprise. The collection survived the Revolution, two world wars, the collapse of the USSR and survived to our days in pristine condition (from the exposition of the History Museum of Russian Chocolate).

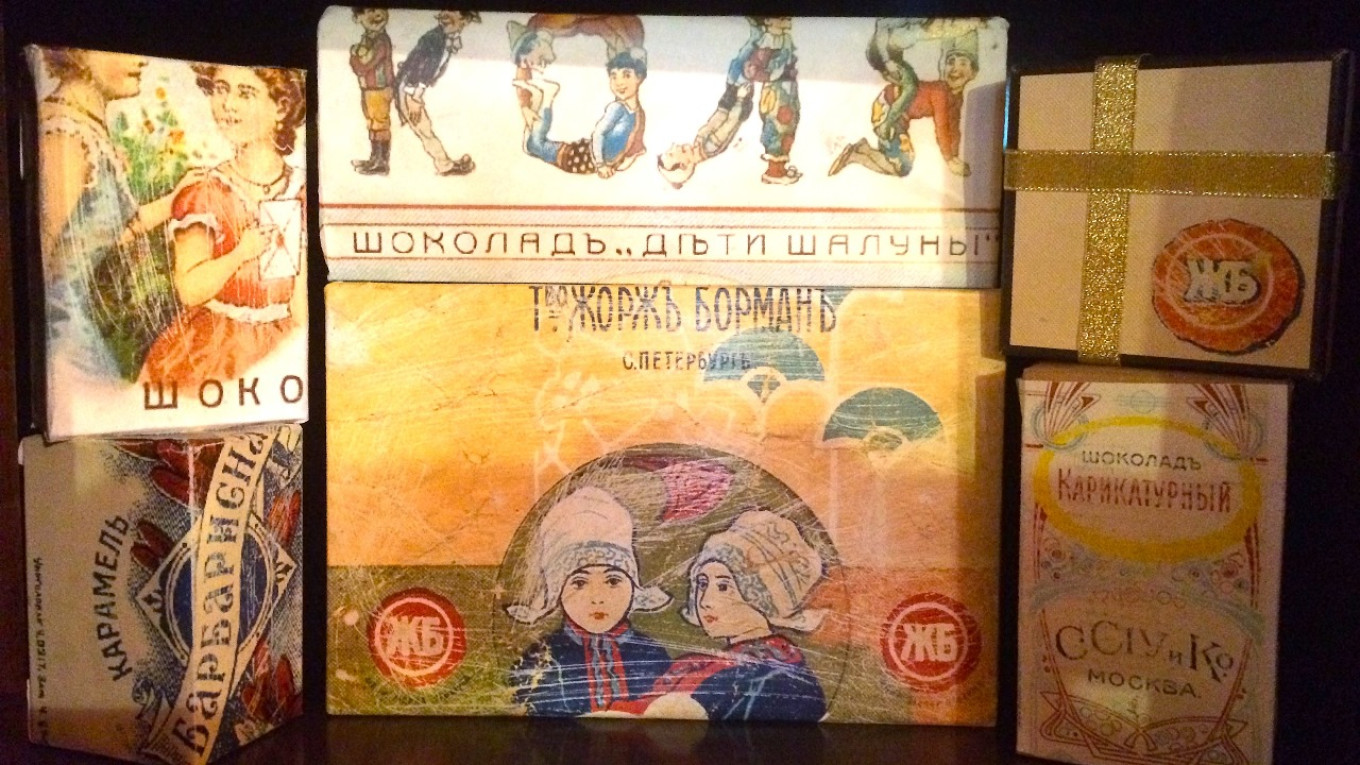

At the beginning of the 20th century there were about 200 chocolate factories in St. Petersburg and 260 in Moscow. It was like an international chocolate cartel. The largest chocolate manufacturers were the Swiss Conradi brothers, the Greek Yani Confectionary Factory, the Jewish company Kaplun, the American Confectionery company Blickgen & Robinson, the German company Einem and Geitz, the Austrian George Borman Confectionary, the French Adolf Sioux, and the Russian Abrikosov. All of them went from small cottage industries to chocolate empires.

The most striking example of success was the Polish nobleman and officer Stanislaw Jakubowski (Jakoubovitch) who was exiled to Vyatka (now Kirov) after he put down the Polish Uprising in 1863. In Vyatka he opened a confectionary line and bakery. In 1907 he was the only confectioner sent to represent Russia at the World Exhibition in Paris, where his chocolates were awarded the Grand Prix and the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

The beginning of the 20th century was the golden age of Russian chocolate. Domestic manufacturers flooded all of Russia with their candies and won prestigious international awards. And the demand was so great that they barely had time to make and distribute their wares before people were clamoring for more.

One of the flagships of the candy business of those years was the firm “Georges Borman.” In 1876 Grigory Borman was awarded the title of “Supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty,” which granted him the right to put the the state emblem on his products. In the same year he opened his confectionary factory’s first wholesale warehouse in Apraksinny Dvor in St. Petersburg. Two years later he opened wholesale warehouses in Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod.

In 1878 the Georges Borman brand was awarded its first gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris. It would receive two more top awards at the Paris exhibition in 1895. And even in distant Chicago consumers loved Georges Borman candies and awarded him an honorary diploma and medal.

Russian confectionary companies were able to send their goods abroad, but they had trouble with distribution inside the country. It took 45 days for goods sent by barge in St. Petersburg to arrive in Nizhny Novgorod. That was fine for shipping hard candies, but delicate chocolates and cookies lost their freshness. Delivery by rail was too expensive.

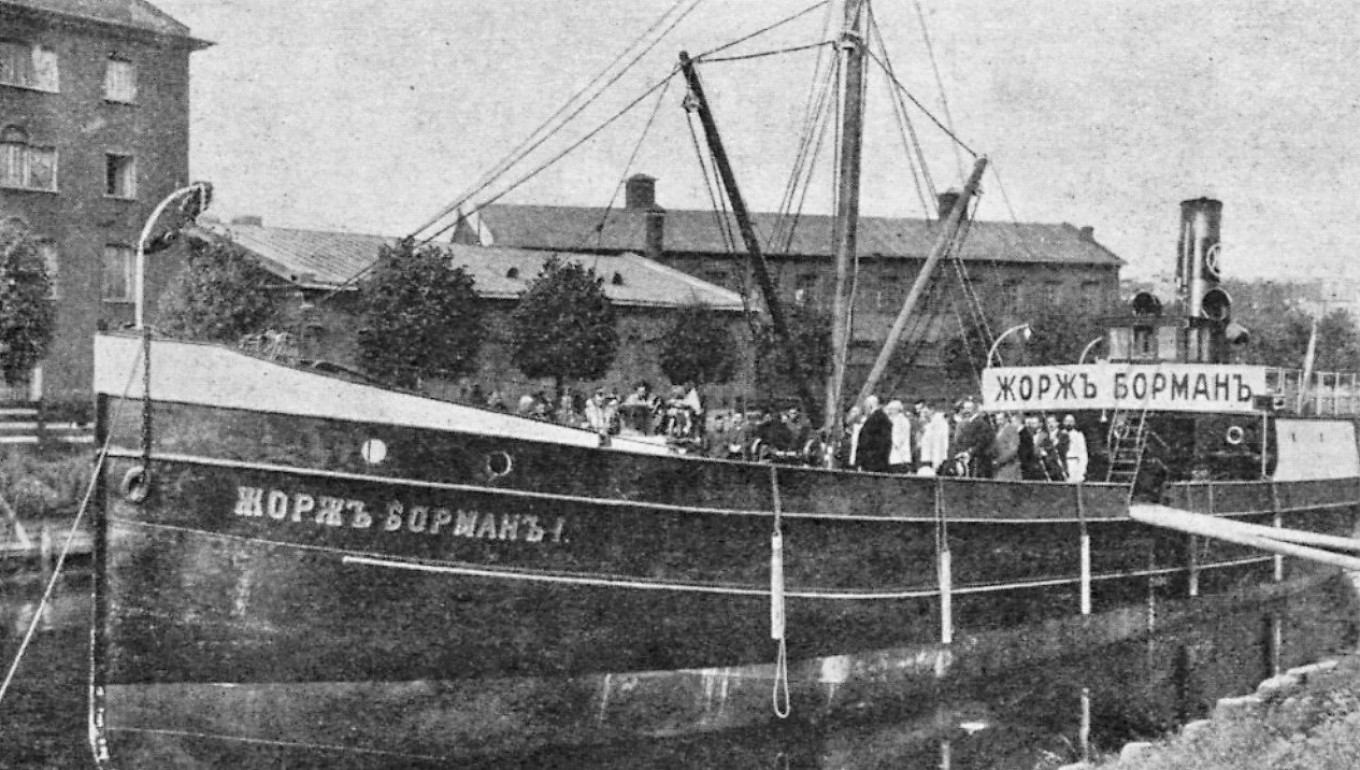

So the company took an unexpected step: it built its own steamships. The first one — the “Georges Borman I” — was christened on July 5, 1912. It could sail both on rivers and in coastal waters of the sea. It had a displacement of 150 tons and a length of 118 feet (35 meters). It could take up to 10,000 poods (163,806 kilos or 361,132 lbs) of cargo in enclosed holds specially adapted for the transportation of candy, cookies and chocolate.

Strangely, if Russian producers were trendsetters with candies and chocolates, they were the opposite with cakes. Chocolate cakes came to Russia as foreign imports, and this trend continued during the Soviet period. For example, many foreigners noticed that the Soviet Prague cake is suspiciously similar to the Austrian Sacher-Torte. Of course, few people in the USSR realized it — not too many people were lucky enough to visit Austria. But in recent decades more people have seen the similarity – and with good reason, it seems.

The Prague cake was invented in the eponymous Moscow restaurant in the early 1960s. That era in the USSR was a time of fascination with the cuisines of the “countries of people's democracy.” The GDR, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, which entered the Soviet sphere of influence after the war, quickly became symbols of European gastronomic culture for the Soviet public that had not been spoiled by many culinary delights. This is when many foreign dishes became part of Soviet cuisine, such as Hungarian goulash, Polish style fish, Bulgarian shopska salad... and when the Sofia, Budapest, and Warsaw Restaurants opened in Moscow.

At this time the pre-revolutionary restaurant Prague in Moscow was reopened. Soviet and Czech chefs started traveling back and forth to share their experience. The Prague cake was just an example of this fruitful cooperation. It’s most likely that when the Czech chefs were visiting Moscow someone came up with the idea of reproducing a famous cake and the Soviet culinary specialists didn’t know that it was a simplified version of the Austrian Sacher-Torte.

Besides, no one wanted to appear to be worshiping anything from the western part of Europe at the time.

Borrowing all sorts of delicacies was not an exclusively Russian or even Soviet habit. The Lviv syrnik (cheesecake) is a perfect example of a chocolate confectionary from Russia’s nearest neighbor that was mastered using some creative innovations. The cuisines of many East European countries share Austrian roots. But Lviv's most famous confectionery became known throughout Ukraine thanks to the culinary specialist Daria Tsvek, whose books were highly prized during the Soviet era.

Today we are free to come up with our own creative version of this familiar dessert. It is the perfect culinary miracle to surprise your guests after New Year's celebrations. The sweet life never ends!

Lviv Syrnik

Ingredients

- 500 g (1.1 lb) traditional pot cheese with 9% fat content (or cottage cheese, see below)

- 70 g (2.5 oz) raisins

- 120 g (2/3 c) sugar

- 100 g (7 Tbsp) butter at room temperature

- 5 eggs, divided (yolks and whites separated)

- 1 Tbsp lemon zest

- 1 Tbsp semolina

- 1/4 tsp salt

For the chocolate glaze:

- 200 g (7 oz) dark chocolate

- 100 g (7 Tbsp) butter

- 5 Tbsp of heavy cream (fat content of 30% or more)

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 180°C / 355°F.

- Press the pot cheese through a sieve. If using cottage cheese or moist pot cheese, strain well beforehand.

- Beat the egg yolks with sugar.

- Add the semolina, butter, raisins, lemon zest and beaten yolks to the pot cheese. Mix thoroughly.

- Beat the egg whites with salt to soft peaks.

- Add the beaten egg whites to the pot cheese mixture and gently blend.

- Grease a baking dish and sprinkle with flour. Pour the pot cheese mixture into the mold and flatten the surface.

- Bake for 40-50 minutes.

- Take the syrnik out of the oven and let it cool.

- Melt chocolate in a bain marie, that is, in a heatproof bowl set it on top of a saucepan filled with a small amount of simmering water; add butter and cream. Stir until combined.

- Pour the hot glaze over the cooled syrnik.

- Chill the syrnik in the refrigerator overnight.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.