In early 2024, the republic of Bashkortostan became the epicenter of some of the largest protests seen in Russia since the start of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Several thousand people gathered outside a courthouse in the small town of Baymak to protest the imprisonment of Fayil Alsynov, a prominent Indigenous Bashkir rights activist. Alsynov was sentenced to four years in a penal colony on charges linked to his role in protests against illegal gold-mining works in the republic’s southeast.

The criminal case against Alsynov was based on a denunciation letter sent to a local prosecutor’s office by the region’s Kremlin-appointed head Radiy Khabirov, a move seen by many observers and activists as an act of personal vendetta for Alsynov’s enduring popularity among locals.

The Russian rights group Memorial designated Alsynov a political prisoner in May.

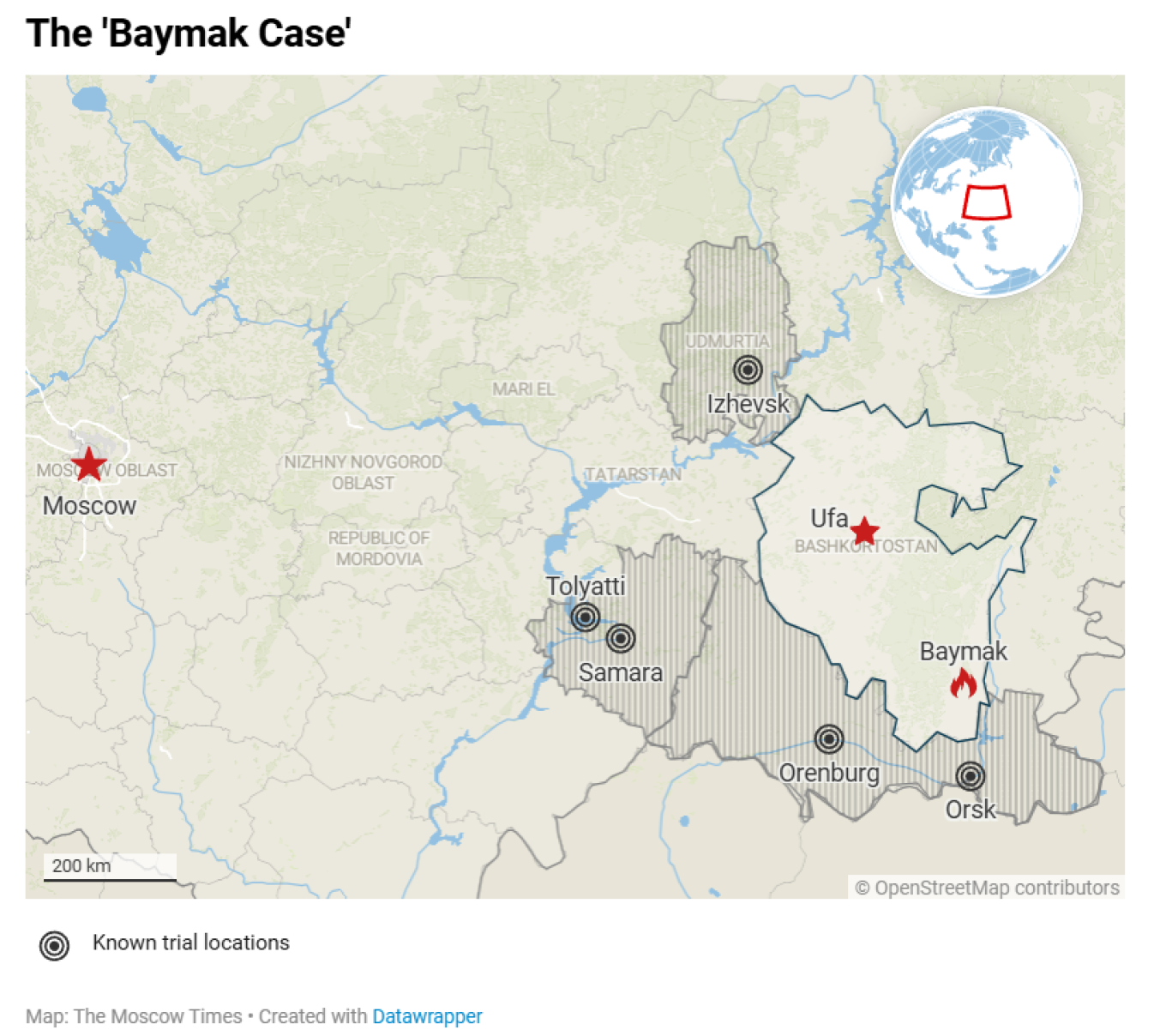

The Baymak protests were followed by sweeping arrests of activists, paving the way for the largest political trial in modern Russian history.

Like in other ethnic republics of Russia, authorities in Bashkortostan maintain tight control over the region’s vast security apparatus, which allows them to execute mass arrests swiftly and with impunity.

Meanwhile, arrested activists had little to no access to independent legal help due to financial constraints, language barriers — many of them primarily speak their native Bashkir language — and a scarcity of qualified lawyers willing to take on a high-profile case.

“The Baymak district is a very compact place, so when you talk to someone now, you always hear that their relative or neighbor or someone from their village has been taken by security forces,” a Baymak district native told The Moscow Times a few days after the protests in January.

More than 70 Bashkir men and women now face criminal prosecution in the so-called “Baymak case.” Among them are people with life-threatening illnesses, fathers with two or more underage children and even entire families.

Defendants are being charged with “organizing and participating in mass unrest” and “using violence” against law enforcement officials, offenses that are punishable by up to 15 and 10 years in prison respectively.

Popular Bashkir blogger and activist Ilyas Bayghusqar, who was arrested in January, is one of the protesters still held in pre-trial detention on charges of “participating in mass unrest.”

While Bayghusqar was under arrest, his wife gave birth to their first child, Asiya.

“I still cannot comprehend that I have a daughter now…probably because I never had a chance to hold her,” Baughusqar said in a letter published on his Instagram account earlier this year.

“The birth of Asiya helped me to understand that there is something worth living and fighting for in this world,” he wrote. “[We set on] the path of fighting for freedom for the sake of our children, to [make sure] that they live better than we do.”

At least one protest participant, 42-year-old Dim Davletkildin, sustained life-threatening injuries during the arrest and two others died under detention.

Rifat Dautov, who was 37 years old, died from internal bleeding after being beaten with a “blunt, hard object” by police officers, according to an investigation by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL).

And 65-year-old Minniyar Bayguskarov committed suicide after possibly being tortured during an interrogation and facing psychological pressure and threats from law enforcement.

Nearly a year since the initial arrests, families of prosecuted protesters remain reluctant to speak to the press or share information about the trials, fearing publicity around their cases could do more harm than good.

Like Alsynov before them, all “Baymak case” defendants were transferred outside of Bashkortostan to stand trial — the authorities’ insurance against further protests.

On Tuesday, a court in the neighboring republic of Udmurtia handed out the latest rulings in the Baymak case. The three defendants, Ilnar Asylgyzhin, Aygiz Ishmurzin and Rafil Utyabaev, were sentenced to nearly nine years in a penal colony — the harshest ruling thus far.

“Why?” the family of Ishmurzin, a 23-year-old singer from Baymak, said in an Instagram story posted shortly after the news of the sentencing broke.

Despite the hardship that comes with being involved in a high-profile — but secretive and lengthy — trial, Baymak defendants and their families still hope for a brighter future.

“It’s hard to believe that it is already my tenth month in prison — one year is coming up soon,” Bashkir blogger Bayghusqar wrote to his family from prison in October, according to a recent post on his Instagram account.

“Allah willing, everything will be well,” he added. “I know that Allah will dispel the dust of lies, and everyone will be held accountable for their words and actions.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.