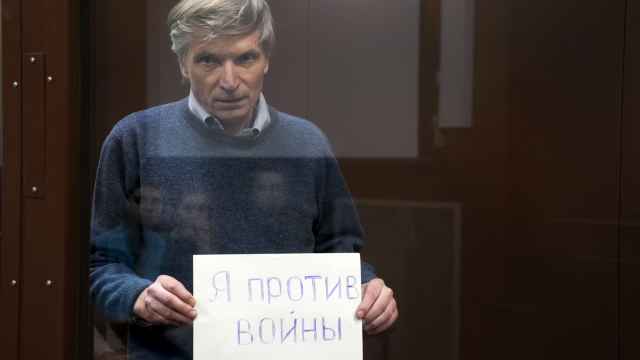

Last December, Boris Kagarlitsky, a Marxist sociologist and professor at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences, was fined 600,000 rubles ($6,600) for “justifying terrorism.” He has since been sentenced to five years in prison. During a video on his left-wing YouTube channel Rakbor, Kagarlitsky said that "from a military point of view, the Ukrainians' decision to blow up the Crimean Bridge is understandable." I also commented on the news in the same video. On the same day as his arrest, my house, as well as the homes of other channel staff, were searched by police.

In contemporary Russia, following the start of the conflict in Ukraine, repression against those expressing anti-war sentiments or criticizing government actions has not just intensified, but become a monstrous norm. Expressing opinions that deviate from the official statements of the Russian Ministry of Defense puts people at risk of arrest and unjustifiably long prison sentences of 7 to 25 years.

It is sometimes argued that the Kremlin regime lacks a concrete ideology. However, are all members of the opposition persecuted equally, regardless of their ideological beliefs?

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has divided all political movements into two groups: supporters and opponents of the war. Yet, according to the Kremlin’s logic, neither side is immune from repression.

Among Russian right-wing activists, positions on the war in Ukraine greatly vary. Some, like the members of the Rusich paramilitary, associated with the Wagner Group, actively support military actions. This group, known for using neo-Nazi symbolism including swastikas and the code 14/88, represents the extremist faction of the right that not only supports the war but is an active participant, fighting on the side of separatists in Ukraine.

On the other hand, there are right-wing nationalists such as Dmitry Demushkin who have voiced disagreement with the Kremlin's policies. After his organization was banned and Demushkin himself was imprisoned for anti-state statements, he openly declared a loss of faith in the ideals of the Russky mir (Russian world) promoted by the Kremlin. Demushkin's criticism of state policy and his subsequent persecution highlight that even among right-wing activists who do not support the war, there is a high risk of repression.

Additionally, there is Yevgeny Dolganov from the musical group Russian Banner who, alongside accusations of neo-Nazism, claims to fight for “our future and the future of our white children." His words reflect the position of some right-wing activists who see the war as defending Russian speakers in Ukraine from being forced to adopt a “false Ukrainian, Russophobe identity.”

Another intriguing case is that of Igor Strelkov, otherwise known as Girkin. Strelkov is known for his right-wing, nationalist views and his support for the Russky mir, which advocates for the protection of Russian-speaking populations outside Russia and the expansion of Russia's influence in the post-Soviet space.

In his public speeches and writings, Strelkov has repeatedly expressed monarchist beliefs and ideas of imperial patriotism. His criticism of the present Russian government and President Vladimir Putin often stems from his belief that the authorities are not going far enough to promote the Russky mir. This places him in a unique position among right-wing activists, where he simultaneously supports the idea of expanding Russian influence but criticizes the methods the state employs to achieve this goal.

In 2023, Strelkov was arrested on charges of public calls for extremism, sparking widespread discussions about freedom of speech in Russia and how authorities handle criticism. His arrest underscores the risks faced by even those right-wing activists who appear to share some of the government's objectives.

Thus, Strelkov represents a complex figure in Russian politics. On the one hand, he is an advocate for expanding the Russky mir, aligning his position with right-wing and nationalist ideas. On the other hand, his criticism of the existing power and subsequent arrest demonstrate that even such views do not protect from repression if they do not fully align with the Kremlin's official line.

Right-wing activists in Russia can be conditionally divided into three categories: those who support the war and actively participate in it, those who support the war but criticize the methods of its conduct, and those who do not support the war at all. The latter two categories of activists may be subject to repression. Essentially, criticism of the government can lead to punishment, regardless of ideological beliefs, though the severity of repression may be linked to ideology, with some liberals receiving longer sentences

The liberal faction seems to have been affected the least by the split. Almost all spoke out against the war, for which they faced severe repression.

Ilya Yashin, one of the loudest voices of the liberal opposition, was sentenced to 8.5 years in a penal colony on charges of spreading "fakes" about the Russian army. His arrest and sentence sent shockwaves through Russia and beyond, serving as a striking example of how the state uses legislation to suppress dissent.

Vladimir Kara-Murza, another well-known liberal activist, was arrested and charged with state treason and spreading "fakes" about the armed forces. Kara-Murza was an active opponent of the war in Ukraine, having long criticized the authorities for repression and corruption and campaigned for human rights.

Alexei Gorinov, a municipal deputy from Moscow, was sentenced to 7 years of imprisonment for a speech that was interpreted as "discrediting" the Russian army.

These cases are just the tip of the iceberg of persecution targeting liberal activists, journalists, and government critics who dare to express their opposition to the war and authoritarianism. The deployment of charges like spreading fakes, discrediting the armed forces, and even treason has become a way to eliminate opposition and silence advocates for freedom of speech and democratic values.

Left-wing activists have also been split over the war. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) and the Left Front are left-wing groups that support the war. However, this could be because the CPRF effectively purged its ranks, removing all those disloyal to the current government. Historian Ilya Budraitskis has highlighted that while the leadership of the CPRF openly supported the war, the only members of the Russian parliament openly disagreeing with the invasion were three members of the Communist Party.

This indicates polarization within the Communist Party, especially among rank-and-file members and activists, many of whom disagree with their leaders' positions. For instance, Mikhail Lobanov, who ran for the State Duma from the CPRF and is known for his criticism of the war, faced numerous repressions. He was repeatedly searched and then arrested for 15 days on charges of disobeying a police officer.

These groups, whose leadership primarily supported the war, saw many rank-and-file members and minorities within the leadership quit in protest against their leaders' pro-war stance. Budraitskis emphasizes that such leftists see the war in Ukraine as a fight against Western liberal capitalism, which they believe would bring Russia closer to socialism. However, reality shows that any form of opposition, regardless of its ideological motives, faces ruthless repression.

Public support for the war in Ukraine does not grant immunity against political repression. Despite supporting the war, Udaltsov and other leftist activists also faced repercussions. Udaltsov was charged with terrorism for supporting members of a Marxist group arrested in Ufa. It seems repression can be based on the class solidarity of the security forces in Russia.

Simply put, if law enforcement charges one group of activists with terrorism, anyone who expresses support for them is automatically considered a terrorist as well, regardless of their political ideology. Kagarlitsky was charged by a similar principle. The prosecution attempted to argue that the video’s title “Explosive Greetings from Mostik the Cat” attempted to justify the Crimean Bridge explosion, which is officially considered an act of terrorism.

After the war began, some left-wing activists left Russia. However, even in the CIS countries, they continue to face political persecution. Evidently, Russian and Kyrgyz security services collaborate closely. In particular, left activists Ryzhkov, Krylova, and Skoryakin were detained by Kyrgyz law enforcement in Bishkek.

Thus, the logic of political persecution of anti-war activists in Russia is not as simple as it seems. At first glance, it may seem that the persecution is associated exclusively with an anti-war position and is equally cruel towards all political persuasions.

But that isn’t actually the case. Liberal anti-war activists are the most persecuted. Any backlash to this is associated with Western elites and LGBTQ+ people by Russian propagandists, which seems to intensify the authorities’ reaction. So let's try to figure out this ideology.

In the absence of a name, the case studies in this article can help us figure out the ideology the Kremlin wants Russians to abide by. Firstly, supporting the war does not in itself provide immunity from reprisals. You need to be not just for the war, but also believe it is being conducted by the state correctly. You must also stand for the same principles as the authorities. The main criterion is your ability to conform, like the Communist Party, by sensing the authorities’ political direction.

Secondly, a person’s political philosophy is less important, though in cases like Strelkov’s, it can shorten their sentence. This shows us that what really matters to the government is supporting the war in the correct way. What unites people punished by the Kremlin is that they deviated from the very subtle, hidden, unnamed ideology of the political elites of Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.