New Year's Eve is just two weeks away, and that means it’s time to decide what to serve on your holiday table. But for us New Year's Eve is also about losing ourselves in old movies. And once again we'll be rooting for the heroes of “The Irony of Fate.”

This time we’ll be rooting for actress Lea Akhedzhakova. Since she opposes the war, half-wit “patriots” have demanded that her face be replaced in the movie by an image created by AI.

But this, too, shall pass, and the New Year's classic film will remain. But in the meantime, as the food crisis gets worse, Russians will have to remember how their mothers and grandmothers coped as they tried to cook a festive feast while waiting — and waiting — for the promised communist abundance.

“Carnival Night” is the first Soviet film that became a part of New Year’s celebrations. Eldar Ryazanov's bright comedy was released in 1956. In February of that year, Khrushchev condemned Stalin’s cult of personality. The country was gradually shaking off the fear they’d felt in the previous era. And by the end of the year theaters were showing a film where people part with the past with laughter and toasts. “Carnival Night” became one of the symbols of the start of the “Thaw.”

This was certainly not a rich era, and so the abundance of dishes, appetizers and fruit on the table looked very festive. It took them more than a week to shoot the final scene of the concert and banquet. And all the food on the tables was real, not fake. The food served on the tables was kept there throughout the filming, and Ryazanov managed to keep the hungry actors from eating it. But time and hot lights took their toll. After a few days, the platters and plates of food began to smell. You have to admire the professionalism of the actors who managed to eat days-old food with such gusto!

Red caviar, cognac, salt-cured fish... The only salad was a fashionable Salad Olivier — or rather Stolichny (Capital) Salad. The French name was not used in official Soviet literature until the 1980s. But it’s not a plain Stolichny Salad — it’s made with baloney (“Doctor’s brand”) or tongue (it’s hard to determine in the photo). This is a good addition. If you are overcome with an acute case of USSR nostalgia, add baloney; but otherwise, boiled tongue is a good substitute. We make a traditional Olivier, but instead of cold cuts we add beef tongue. Be sure to add chopped pickles for a touch of color and flavor.

“Do you think potatoes are simple — just boil and eat?” “Not at all!” said the very funny cook Tosya Kislitsina in the movie “Girls” (1961). “You can make so many dishes from potatoes!”

“Count ‘em: fried potatoes, boiled potatoes, mashed potatoes, French fries, potato pie. Potato pies with meat, with mushrooms, potato pancakes, potato casserole...”

And these brings us to the classic Soviet holiday main course: meat “French style.” Today we’d simply call it “potato gratin with pork baked in mayonnaise.” But in those days hardly anyone knew that no Frenchman would ever think of baking mayonnaise. This was a legendary hearty and delicious dish, which of course had to come from enchanting France. And legends, as we know, don’t have to be true.

Everyone remembers the discussions of food in in the movie “The Irony of Fate” (1975). “This fish in aspic is disgusting!” This phrase by Ippolit is now a catchphrase. But few people know where it came from.

Ippolit wasn’t the only character who didn’t like Nadia’s fish in aspic. When Zhenya Lukashin tastes it, he also seems puzzled as he tries to sort out the gamut of flavors, “This isn’t fish, it’s not fish in aspic… it’s… it needs horseradish.” Is Nadia such a bad cook? It doesn’t seem so. The characters tuck into everything else she has cooked. So why did the director draw attention to the fish in aspic not once, but twice?

It turns out to be a joke of its era.

In the late 1960s the USSR began industrial fishing in the ocean on a mass scale, in part to replace meat that was in short supply. Strange names appeared on the shelves: pollock, notothenia, poutassou… No one knew how to cook these new kinds of fish. Fry? Boil? Bake? Or maybe pour cooled broth over it to make aspic? They cooked it with the skin on, which made the dishes bitter. So the scene from the movie is about these experiments of Soviet housewives.

“I make that salad better than your wife. You need to add grated apple,” Olga Ryzhova says in the movie “Office Romance.” At that time, it was clear to every viewer that she meant the most delicious variation of Olivier. By 1977, Salad Olivier (although still not officially called this), was firmly a part of the Soviet kitchen repertory. And since there was no canonical recipe, each hostess tried to improve the salad to the best of her talent and ability. Adding sour green apple (grated or in pieces) made the salad more appetizing. And the whole recipe is extremely simple: “Take 300 g of Doctor’s brand baloney or boiled chicken, boiled carrots, 1 fresh and 1 pickled cucumber cut into cubes. Add 200 g of canned peas, 1 grated apple and dress with mayonnaise.”

Luckily neither the audience nor the characters in the film could guess that in ten years they’d have to stand in line to buy even a jar of mayonnaise. And canned peas would be part of the “meal package” people could order at their workplace just a few times a year before major holidays.

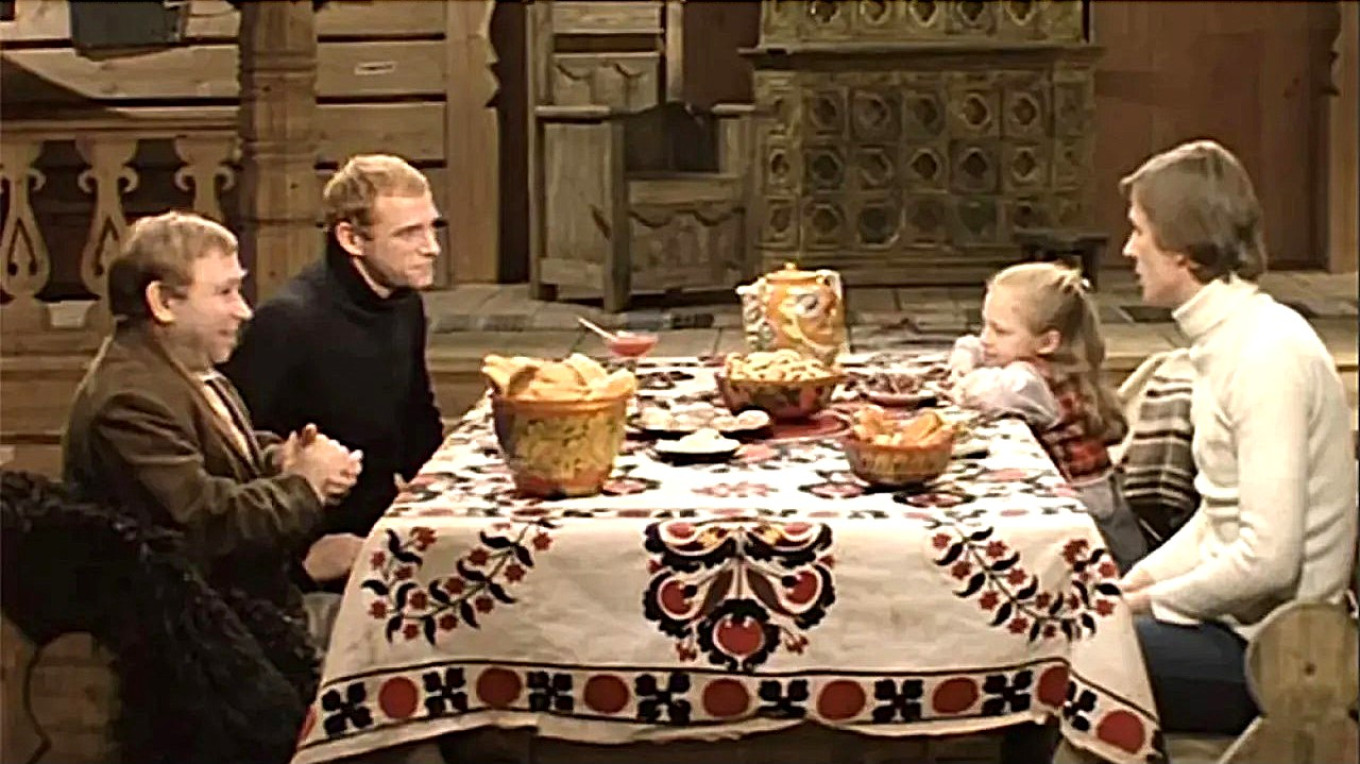

Meanwhile, socialism was coming to an end. And the holiday feast, even in the fairy-tale version, was becoming more and more modest. The movie “The Wizards” (1982) only confirmed this sad truth. The New Year's table is nothing like the abundance of “Carnival Night”: Soviet champagne, lemonade, green apples, and pirozhki (filled pastries), an indispensable part of the Soviet menu of the 1980s. Each hostess made them in her own way: filled with meat, cabbage, eggs, apples or jam.

Cabbage and carrot pies, Mimosa Salad, cookie “potatoes” and many other Soviet holiday dishes are still remembered with nostalgia and associated with the “flavors of childhood.” But at the same time, we remember a popular phrase from that era: “There is a lot of spiritual food around, but nothing to eat.” Food — or the lack thereof — was one of the few topics that people could joke about.

Soviet salads not only made a festive table, they fulfilled the most important function of providing something good to eat. That is why they were rich — made with meat, eggs, mayonnaise and vegetables.

Here is a delicious salad that we have been making and serving at holidays for many years.

Spicy Potato and Bacon Salad

For 8-10 servings

Ingredients

- 4-5 potatoes

- 1 large red onion

- 4 medium pickles

- 100 g (3.5 oz) green olives stuffed with red pepper

- 1 tsp garlic powder

- 2-3 Tbsp dill

- 4 stalks green onion

- 300 g (10.5 oz) bacon

For the dressing:

- 3/4 cup mayonnaise

- 1 Tbsp Dijon mustard

- 3/4 tsp Tabasco sauce

Instructions

- Boil the potatoes in their skins. Cool completely and cut into small cubes.

- Cut the bacon into 2 cm (1 inch) wide strips and fry until they are as crisp as bread crumbs, being careful not to let them burn. Drain the bacon on a paper towel to absorb the excess grease.

- Dice the cucumbers and onions; cut the olives into rings. Slice the green onion into small pieces and chop the dill. Gently mix all the components with the potatoes and bacon. Sprinkle with garlic powder.

- Prepare the dressing: Mix the mayonnaise with mustard and tabasco sauce. Pour the dressing over the salad, stir it and put it in the refrigerator overnight.

- Do not taste it! If you do, there will be nothing left for New Year’s Eve.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.