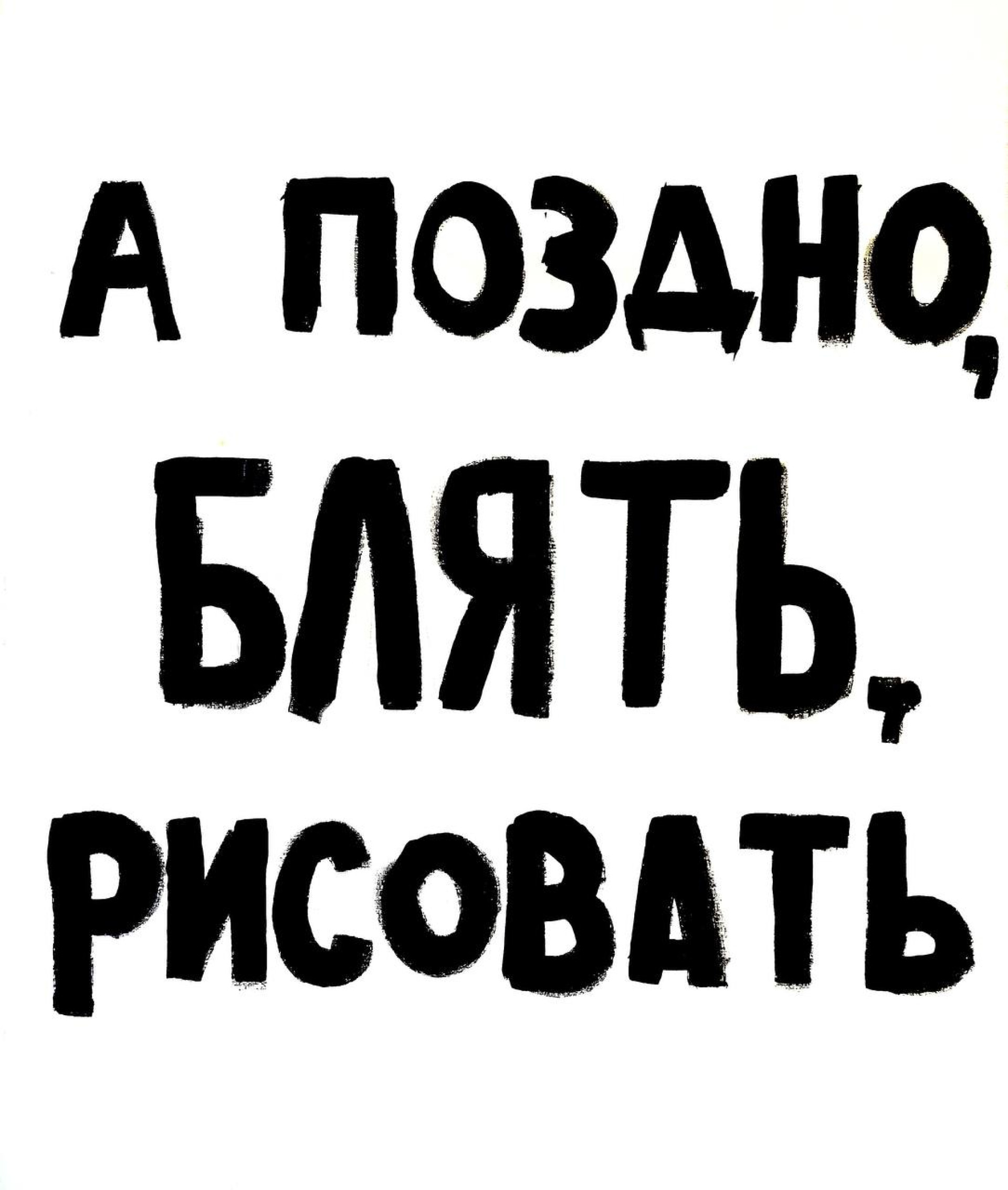

Dissident artist Nadya Raplya expressed a feeling shared by many of her peers when, in her first artwork after the invasion of Ukraine, she painted the words “It's too f***ing late to draw” on a blank canvas.

In Moscow, she and her fellow members of АХУХУ, a collective of anti-Kremlin artists, faced persecution by the Russian authorities until the invasion of Ukraine forced her and many others out of the country.

Now based in Berlin, Raplya, a graduate of the British Higher School of Art and Design, is a prominent figure in the exiled dissident art community. In addition to being a member of АХУХУ, she is part of the production team at All Rights Reversed gallery.

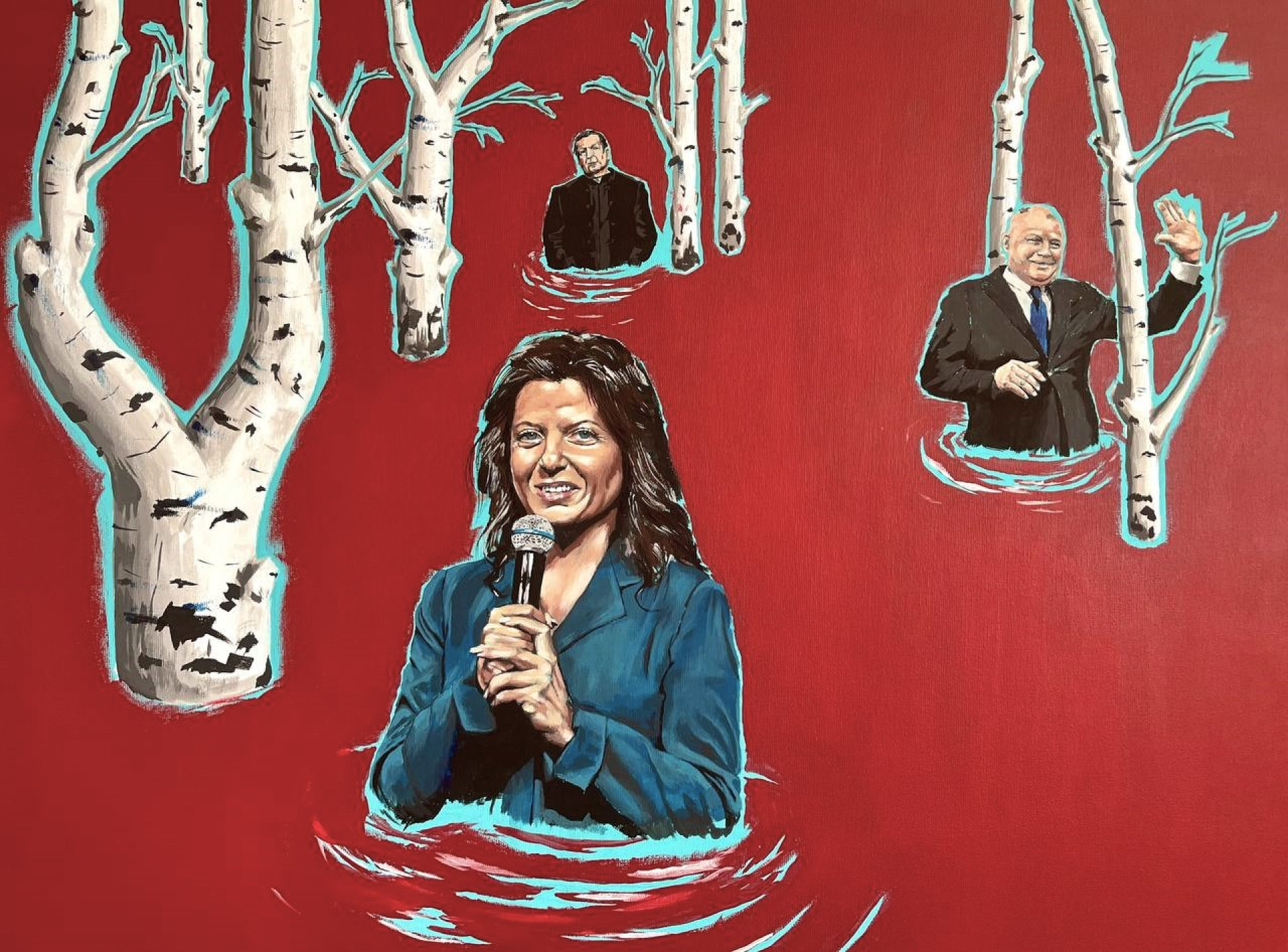

Her work has been exhibited at Artists Against the Kremlin and Women Against the Kremlin, two events co-organized by The Moscow Times this year in Amsterdam.

Raplya spoke to MT about using art for political expression during wartime, artistic repression inside Russia and rediscovering her creativity in exile.

The Moscow Times: Your most famous work is probably the canvas that says ‘It’s too f***ing late to draw.’

Nadya Raplya: Yeah, unexpectedly. It took so many years of art education just to end up putting four words on a white canvas.

Tell us about the idea behind it. If it’s too late to draw, then what do you do?

First of all, the piece itself is a bit absurd. ‘It's too f***ing late to draw’ — well, f**k, it's drawn on a canvas.

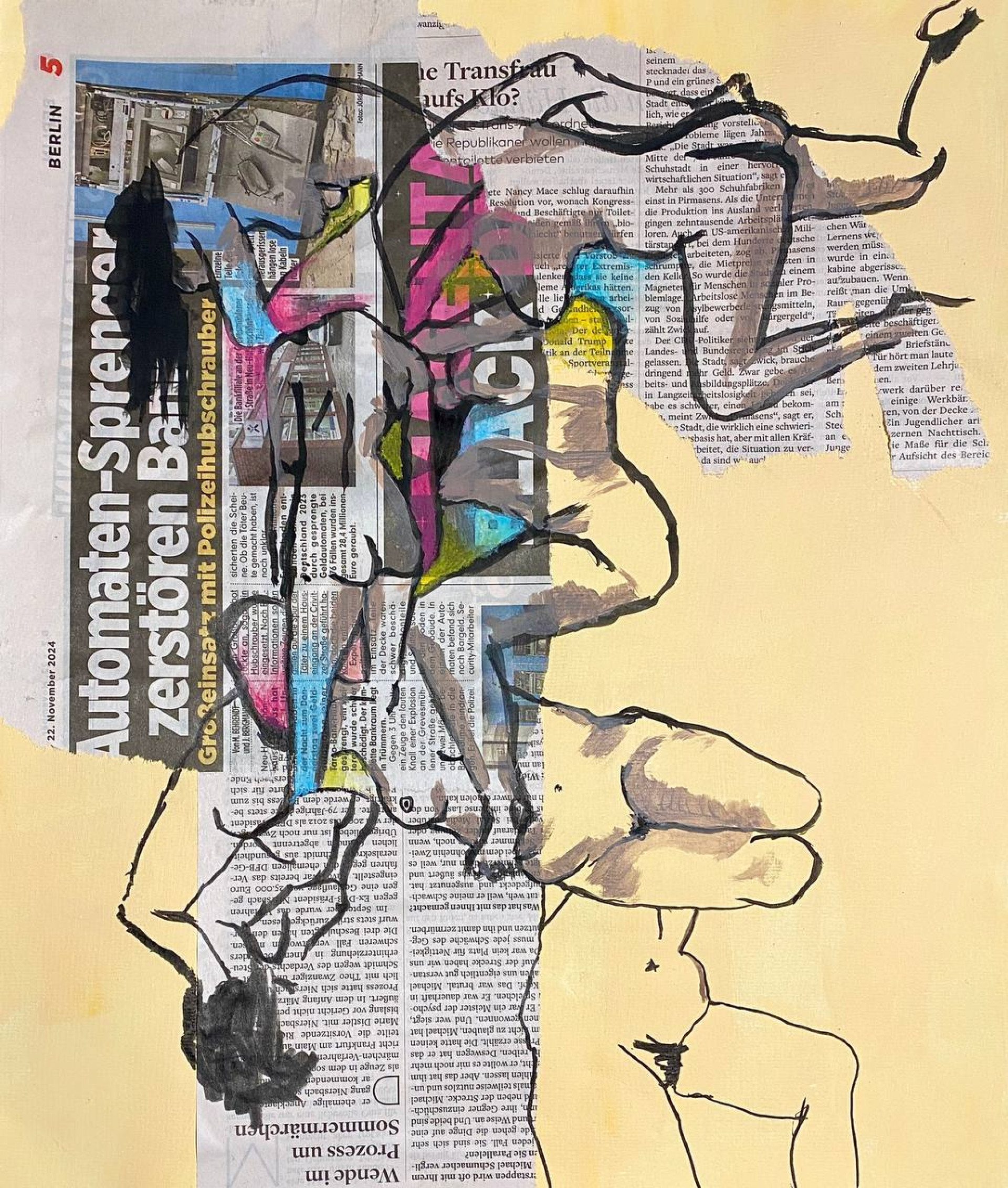

It was 2022, the beginning of emigration, total despair, not understanding what was happening or what to do next. I probably didn't do any creative work at all for six months, I was in total shock. I came here to Europe with one backpack and I was busy getting a residence permit and looking for an apartment. This was the first canvas I bought — I didn't bring anything with me, because I thought I'd be back soon.

I bought a canvas, bought some colors, sat down to paint for the first time in six months and realized that I couldn't express all this storm of emotions in any figurative form. It was just an outburst of anger: What can I even draw here, what can I even say here, and yes, it's too f***ing late to draw.

I wasn’t even thinking about displaying it somewhere, I just sent it to my curator as a joke. And he was like, ‘Cool, we'll take it.’ It ended up becoming a manifesto for all the artists in our exhibitions. It's our bestseller.

I wonder, if you expand upon this thought, is it not anger at artists too? If it's too late to draw, does it mean that something should have been done earlier?

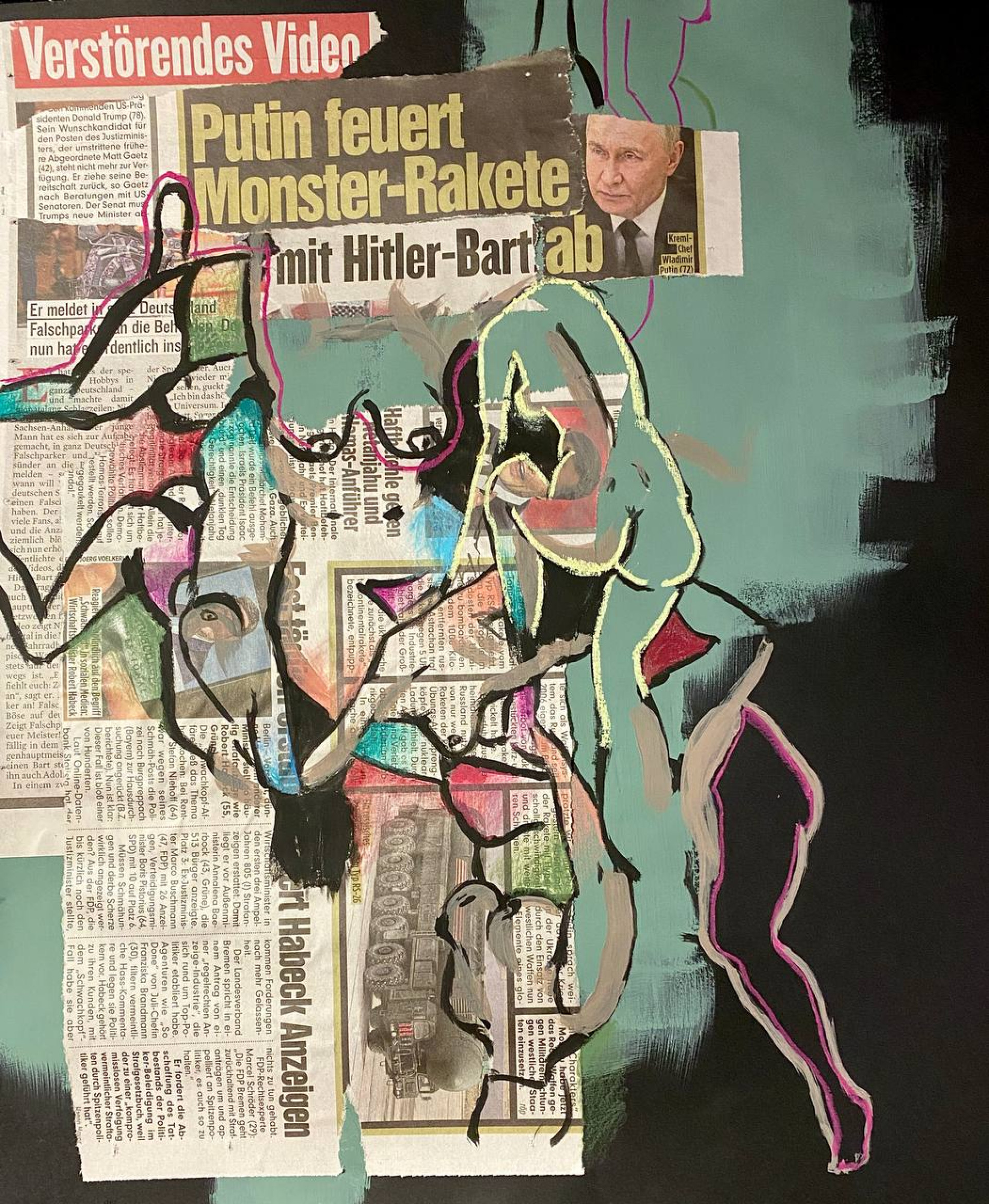

Yes, perhaps it was also anger at artists who decided they were staying out of politics. Although I believe that there is no such thing — art cannot be apolitical. At people who said that ‘We're making some kind of high art, we're above all this.’ Some changed their tune with the beginning of the war and finally started speaking about what was happening — but it's too f***ing late.

How and why did you leave Russia?

I left right after the war started, on the morning of March 22. I was just personally absolutely disgusted by what was happening. I was going through a personal tragedy.

I spent some time in Ukraine and traveled there as a child. I have a childhood best friend from Poltava. In general, I have a very anxious and hysterical personality, so I was in complete hysterics, stuffing things into my backpack and thinking how surreal everything was. I thought this couldn't be happening and that it would all be over now and I'd be back in a couple of weeks, a couple of months at the most.

And you had to leave your career in Russia?

I was mostly doing underground art in Russia, and here, you could say, there was a big step forward.

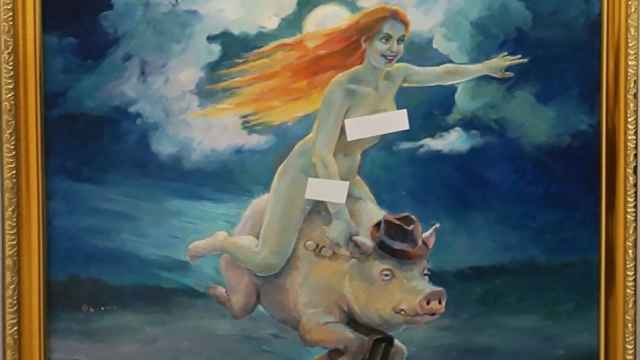

In Russia, I graduated from university in 2020, and I worked in a restoration workshop for a while. We also had an art group, an art community, called АХУХУ [an acronym for Assotsiatsiya Khudshikh Khudozhnikov, or the Worst Artists’ Association]. There were exhibitions in Moscow and St. Petersburg. In 2019, the riot police came to one of our exhibitions. We were holding the opening on Putin's birthday, October 7. The exhibition was called ‘Autumn of the Pakhan’ [a Russian slang word for a crime boss]. The police arrived, they threw everyone out into the street, tried to weld the doors shut, it was insanity.

Naturally, all the venues and galleries refused to cooperate with АХУХУ after that. There were some underground lofts and factory premises where we could display our work instead. The curators did not inform visitors of the address in advance; they would drop it an hour before the opening.

Did you feel that you were continuing the work of late Soviet artists who organized exhibitions in the forest in the 80s because they were not given exhibition spaces?

Yes, of course we did. When I was in Russia, I felt that I was doing something brave, something significant. But in Europe, I felt as if I was just posing. I left, and I'm shouting from afar: ‘you guys in Russia are assholes.’

Why did you choose such a name for the association — ‘The Worst Artists’?

Basically, these were originally social media groups: associations of the worst writers, the worst journalists, the worst musicians. Akhuli, Akhuzhu, Akhumu. Why the worst? Firstly, because none of us are trying to fill the niche of the best. We're such art world punks. And now we even feel proud of it. The worst artist: You have to earn that too, that title.

You've said it's hard for you to break into the ‘official art’ world.

It's difficult for us to find any adequate funding in Europe. Because we are not high art, the world of European gallery art.

Everything with us is more straightforward, more direct. We more often make a specific statement, we talk about specific political and social phenomena. Local cultural figures find this too straightforward. That's why local art institutions are not so interested in us. Although ‘It's Too F***ing Late to Draw’ sold for a fair sum — I don't want to name it — but this rarely happens.

Gallery art has a more complex narrative, where even a cultural worker can't immediately understand what it's about — you need explication and preparation for exhibitions. But we convey a direct, concrete idea from the artist to the viewer.

What are your favorite works that you've done?

I mostly do paintings, but my favorite work is an installation that I did a few years ago at an exhibition at the Uspekh bar in Moscow.

In the bar’s restrooms, I placed gilded frames with glass and my signature in the toilets. That is, visitors had to urinate on these frames with inscriptions next to them like: ‘Can I feed myself with art?’, or ‘I dedicate this artwork to my mother.’ There was also, ‘Relax, now tense up, we will create art.’ It was a reference to the work of the conceptual artist Yuriy Albert, who did text-based work, and to Marcel Duchamp’s urinal.

It was basically about the nature of contemporary art: some people think it's sh**, but you can make art out of that sh**. It’s also about what rights an artist has in a gallery, what he keeps for himself and what he gives to the viewer, and about the idea of the death of the author when the viewer contributes his own reading.

Do you expect or hope to return to Russia?

Of course. I really want to. I did and am doing all this not out of hatred for this country, but out of a great and deep love for it. Yes, I really want to go back. I really hope so. But now I'm in the process of trying to accept that it might never happen, because it's impossible to live in anticipation for so long. I'm in my third year of emigration and I've only just started to build my life. But if I suddenly find out that everything is over, Putin is dead, all victims of political repression have been granted amnesty and no one will be imprisoned, then yes, I will probably be in Moscow tomorrow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.