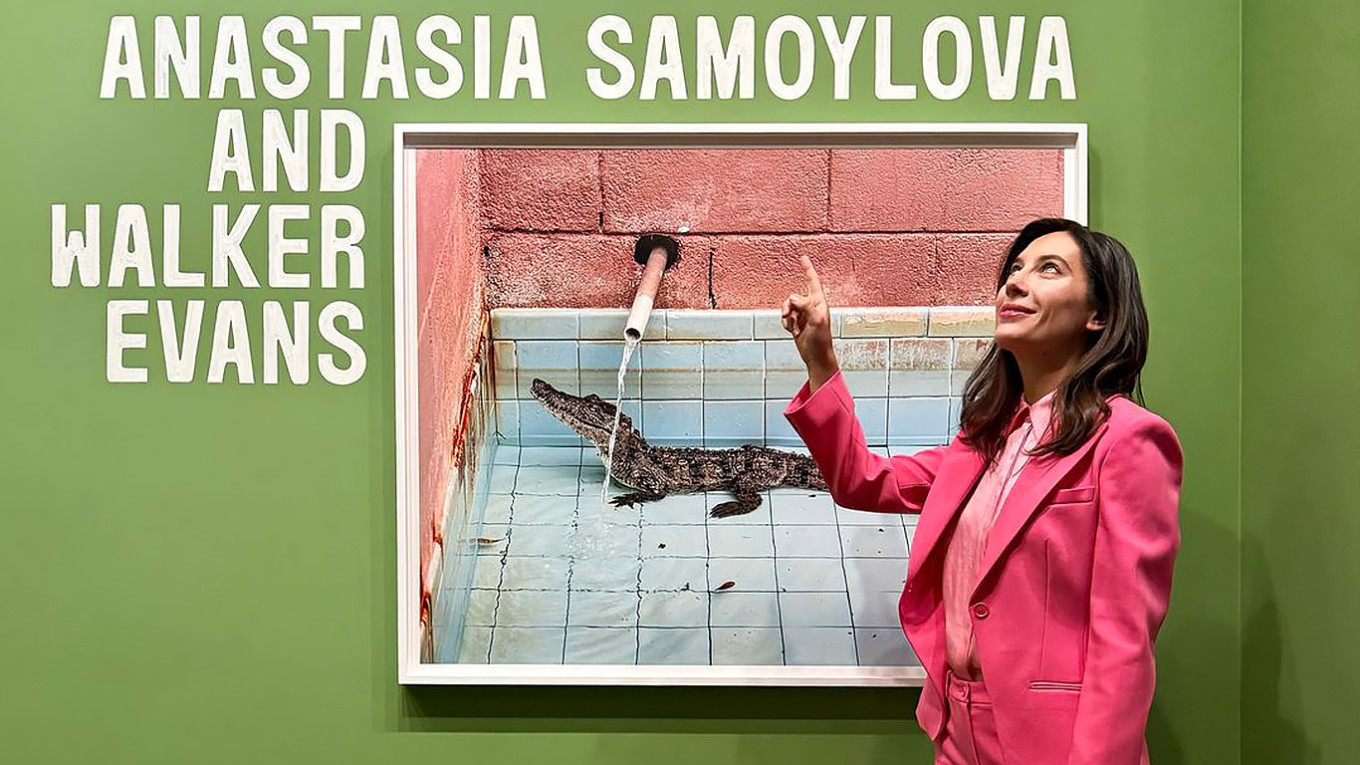

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York recently opened a solo exhibition by Russian-American artist Anastasia Samoylova. Titled “Floridas,” the exhibition features Samoylova’s works alongside those of Walker Evans, a quintessential figure in American photography.

“Floridas” marks the first exhibition at an institution of The Met's stature for a Russian-born artist of her generation.

The Moscow Times spoke with Samoylova about her journey to this milestone, her achievements and her future projects.

Andrei Muchnik: A solo show at the Met is quite an accomplishment for a contemporary artist. How does it make you feel?

Anastasia Samoylova: A solo show at The Met is a profound milestone, and it fills me with immense gratitude. It's not just a personal accomplishment but also a reflection of the collaborative efforts of the curator, peers and supporters who have championed my work over the years. Exhibiting alongside a historical icon like Walker Evans has pushed me to think deeply about the legacy of photography and my role within it.

This moment at The Met is a celebration, but also a reminder to keep looking forward — to remain curious, responsive and engaged with the world around me.

So how did ‘Floridas’ come about?

I ended up in a strange place — Florida. The premise behind my show is that America doesn’t want to see it, but Florida is everywhere. It has this facade-like quality. There’s a very strong mythology around it, like the idea of the American dream, and in a way, I’m a testimony to that.

I put together this book called ‘Floridas’ two years ago — my images along [with] those of Walker Evans. So I had to request the files from The Met to include them in my book. That’s how I met with Mia Fineman, the curator, and then she offered me a show.

At the beginning, your project did not involve Walker Evans?

I had another book that came out in 2019 called ‘FloodZone.’ And Florida is quite represented there, but there are other states as well. It’s about life on the coast and the climatic issues. I had an excess of images and I wanted to delve deeper into Florida. Then I saw that Evans also photographed there and I wanted to add those images as well.

When did you move to the U.S.?

I moved to the U.S. in 2008. I got my first degree in environmental design from the Russian State University of Humanities (RGGU) in Moscow the year before and started contemplating an MFA program in the U.S., as no such program existed in Russia. I thought if I got a full assistantship then I would go, and that’s what happened. It was a private university in the Midwest, Bradley University. It’s kind of in the middle of nowhere, Peoria, Illinois, and they offered me a full assistantship. I taught digital photography there and that way my MFA was free.

And you decided to stay after that?

I didn’t know how it was going to play out at first; I didn’t know anybody in America. But it so happened that I was offered a position to replace my professor because she retired. So I did a one-year replacement teaching at Bradley and then I got recruited for a full-time teaching position at Illinois Central College, a community college. I became the head of the photography department and that’s how I got my work visa.

Are you still pursuing a career in academia?

No, I quit eight years ago. In 2016 my family moved to Florida and I became a full-time artist.

When did you realize you wanted to be an artist?

I’ve always wanted to be an artist, for as long as I can remember. When I was young, I attended children’s art schools. My mom recently visited and brought a video archive. When I was 11, we made a spoof of the old Latin American soap operas that were always on my grandma’s TV. There was a creative side to me very early on.

I’m from a small town in the Stavropol region, Donskoye. [Mikhail] Gorbachev was born somewhere nearby. When I was five, my mom remarried, and we moved to Moscow. But I have very fond memories of Donskoye. When I moved to Peoria later, it actually reminded me a lot of my hometown — you know everyone, and you can walk anywhere.

While still a student, I got a job at Mercury, Russia’s largest luxury retailer. A friend asked me to sign postcards for their clients for Christmas. While in the office, I overheard a conversation about them needing an event photographer, so I said, ‘Take me, I’ll do it for free!’ They gave me a chance, and the celebrities at the event loved the pictures, including Larry Gagosian, Ksenia Sobchak and Dasha Zhukova. After that, I was booked almost every weekend, and they started paying me.

That job led to another gig as a shop window decorator for Armani Casa on Tretyakovsky Proezd [a luxury shopping street in central Moscow]. It taught me so much about composition. The window was essentially my exhibition space, and I had to change it every couple of weeks.

It was a series of chances, but I was ready to take them. That work helped me build a decent portfolio, which I used to apply to art school.

Were you also making art throughout all this time?

As much as I could, because I was working full time. But when I moved to America, the hope for a career in art became a lot more feasible.

While teaching at that small college in Illinois, I got an email from The New Yorker. At first, I couldn’t believe it — I kept refreshing the screen, thinking it was spam.

It turned out they had found me online and wanted to feature one of my early projects, ‘Landscape Sublime.’ It was very constructivist, inspired by my architectural studies and my favorite painters, Natalia Goncharova and Alexandra Exter — the Amazons of Russian avant-garde. The New Yorker featured the work, and it’s still online.

I had a few exhibitions locally in Peoria and attended some festivals, so it was a very gradual build-up. The idea that I ‘emerged overnight’ is completely false. Right now, I have a show at an incredibly prominent institution, but I’ve been exhibiting this whole time, for 17 years.

Today you are focusing on eco-photography, and your works are mostly landscapes and buildings, but not people. How has this direction emerged?

I’m naturally drawn to architecture and places because that’s what I studied and what interests me. People are secondary for me, though now they show up more as I’ve become comfortable talking to people in the streets.

I have a slightly detached perspective. I never claim objectivity on any subject because I’m not a photojournalist, so I don’t owe an illustration to any particular narrative. I can be abstract. I’m an artist working with photography — that’s how I define what I do.

Have you had any exhibitions in Russia?

There was another project called ‘Image Cities,’ where I visited 17 global cities, including Moscow. It was a survey inspired by Jacques Tati’s movie ‘Playtime,’ which I absolutely love. That was my last visit to Moscow, in June 2020, and the first time I really photographed the city.

I asked the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow for an artist residency, and they generously offered me that opportunity. I spent three weeks photographing the city, which led to my exhibition at the Moscow Photography Biennale in 2021 — my only exhibition in Moscow.

The exhibition, however, focused on another project, ‘FloodZone,’ which was inspired by [Soviet film director] Andrei Tarkovsky. Tarkovsky’s demand for slow contemplation from his viewers is something I strive for in my images. They aren’t for quick consumption — there’s rarely any drama or action. I want viewers to stop, look, and unpack the layers, and that’s very intentional.

Do you consider yourself a Russian-American artist or mostly an American artist?

You always have to give your biography, but in terms of who I am, in terms of my identity — I grew up in Russia and always felt like I didn’t quite fit in. I think that feeling is almost a prerequisite for becoming an artist anywhere. You find like-minded people, free thinkers, from creative fields, and that becomes your community. At least, that’s been my life experience. So I think that would define my identity more than any specific nationality.

In the current political climate, has being from Russia influenced your career in any way?

Of course. I’m getting trolled all the time. I’ve had to develop really thick skin. It’s sad to be trolled just for being born there. It’s not like I’m going to resign from certain aspects of the culture. Someone once tried to troll me, saying, ‘Oh, you’re advertising your Russian heritage.’ And I just thought, what heritage are you talking about? I was born there.

Where does this trolling occur? Online?

Online and in person. I gave a talk last year at an institution during an exhibition, and someone in the audience stood up and tried to harass me for being born in Russia. Thankfully, I had friends from Germany and America there who had my back. I don’t know what it’s like outside of the art bubble, but within it, I feel protected and safe.

What are your plans for the future?

I'm already immersed in my new project, ‘Atlantic Coast,’ which retraces Berenice Abbott's journey along Route 1. It's a continuation of my exploration of place, history and the evolving American landscape, but with a new lens on the environmental impacts of shortsighted development and dependence on fossil fuels. The series will be published by Aperture in 2025 and exhibited at the Norton Museum of Art and the Johnson Museum of Art in 2025 and 2026, respectively.

“Floridas” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 11, 2025.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.