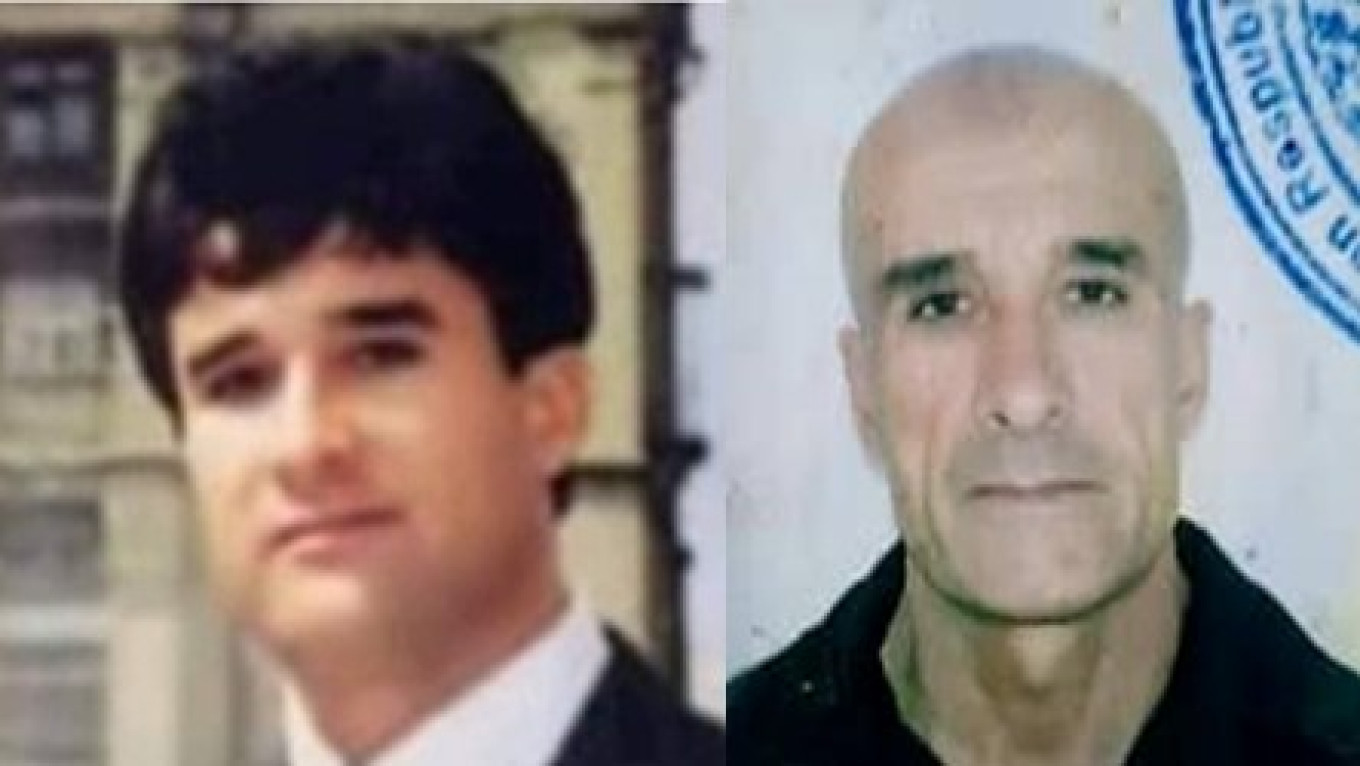

In 1999 Yusuf Ruzimurodov, a journalist, human rights activist and dissident, was arrested by the authorities in Uzbekistan for criticizing President Islam Karimov and sentenced to 15 years in prison. But his term was extended twice, and in the end he spent 19 years in prison – the longest prison sentence served by any journalist in the region for his professional activities.

After he was freed from prison in 2018, Ruzimurodov renewed his work as a journalist and human rights activist and faced renewed persecution from the Uzbek authorities. In 2020 he moved to Tbilisi, Georgia, where he continued his work. He eventually moved to Riga, Latvia in 2022 with the help of the Media Hub, an organization that provides support to independent journalists from the CIS.

In Riga, in addition to working as a journalist, he was able to finish writing his memoirs in Uzbek and then translating them into Russian.

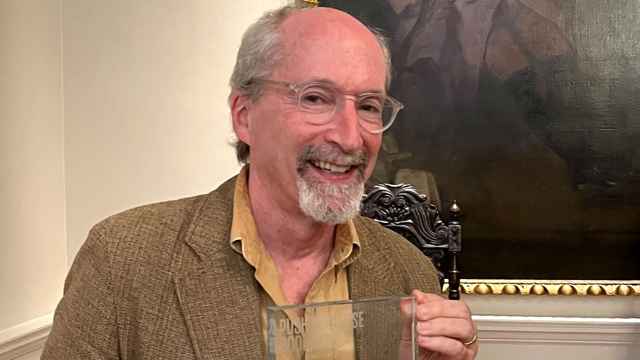

At an event organized by the Media Hub to celebrate Ruzimurodov’s completion of two versions of his memoirs, he discussed his path to dissidence, journalism and prison with another journalist in exile, Kirill Nabutov.

Ruzimurodov began his journalism career in the newspaper “Erk,” the mouthpiece of the only opposition party registered in Uzbekistan at the time, the “Erk” Democratic Party. When Karimov's regime began to eliminate dissent in the country, the editorial board of the “Erk” newspaper was at the top of the black list.

On February 7, 1993, the newspaper was closed by the authorities and moved its editorial offices to Astana, the capital of neighboring Kazakhstan. Ruzimurodov worked in Astana and distributed the newspaper in Uzbekistan. On January 10, 1994, Yusuf was detained in his home in Astana by Uzbek counterintelligence officers. He was transported to Almaty, then the capital of Kazakhstan, where Yusuf managed to slip away from the officers.

In early 1995, he and his wife moved in Kyiv. Together with other opposition activists he resumed publication of the newspaper. Yusuf was also actively involved in the Uzbek service of Radio Liberty, where he covered socio-economic problems and the egregious human rights situation in Uzbekistan.

After a series of bombings in Tashkent on February 16, 1999, mass repression began throughout the country. On February 17, Ruzimurodov made a special appeal on Radio Liberty to President Karimov to ensure objectivity in the investigation of the bombings and to prevent unjustified repression. This and his previous activities led to his detention, extradition to Tashkent, trial and first prison sentence of 15 years.

In the prison colonies Yusuf was constantly pressured to renounce his beliefs and to petition the president for a pardon. But Ruzimurodov refused. On March 7, 2014, a week before the end of his term, the court added another three years and six months to his sentence. And when these three and a half years had passed, once again on the eve of the end of his sentence, a court added another three years and ten months in prison.

In protest Ruzimurodov went on a hunger strike, allowing himself only two or three sips of water a day. Weakened and stick thin, his cellmates put three mattresses on the floor of the cell to cushion his body. He was, he said, “ready to die.”

But by this time former Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev was now president and wanted the world community to see him as a reformer. After 94 days on a hunger strike, on February 22, 2018, Ruzimurodov was finally released.

Yusuf resumed his journalistic activities almost immediately. Through his websites and media outlets, he began to publicize human rights violations in Uzbekistan, particularly those related to illegal house demolitions and other forms of official abuse of ordinary citizens. He also sought to draw the world's attention to the genocide of Uighurs in China. He strongly opposed the persecution of political opposition in Russia and Belarus. Together with other former political prisoners and with the support of Amnesty International, the International Federation for Human Rights and other international organizations, Ruzimurodov began collecting materials to rehabilitate the political prisoners repressed by the Karimov regime.

His activism predictably alarmed the Uzbek authorities. With the help of human rights organizations, Ruzimurodov left Uzbekistan for Georgia, then Turkey, and finally Latvia.

From "Memoirs" by Yusuf Ruzimurodov

Bombings in Tashkent. Detention in Kyiv. Illegal Extradition

On February 16, 1999, a series of explosions took place in Tashkent. At the time I was in the bureau of Radio Liberty on Khreshchatyk Street in Kyiv.

The news program “Vesti” was giving details of what had happened. President Karimov was giving an interview from the scene just as there was another explosion right behind the president’s back. But the head of state calmly looked back in the direction of the explosion and continued speaking in front of the TV camera as if nothing had happened.

That’s where the scriptwriter made a mistake. It made no sense that Karimov, who was always deathly afraid of the most ordinary peaceful rallies, could calmly stand right next to a place where his life was in real danger — especially since this was the sixth explosion in a row.

According to protocol, before the head of state arrives at any site, the security service needs at least 12 hours to inspect it. If the site is not safe, the guards will prevent the president from going there. In other words, Karimov and his accomplices knew exactly how many bombs were planted and when they would explode. A safe place for the interview was also carefully chosen.

When I saw this news clip, my first thought was: “They organized it themselves!”

On February 17, I made an address to the public and President Karimov on behalf of the Information Center of the “Erk” Democratic Party on Radio Liberty:

“On February 16 of this year a series of explosions occurred in the capital of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, resulting in civilian casualties. There are dead and wounded. The Information Center of the “Erk” Party expresses deep condolences to the families of the victims and sympathizes with our injured compatriots. We are deeply concerned about the crude nature of the investigation carried out immediately after the crime was committed. For example, the detention of the mother of the religious figure Obidhon Kori contravenes procedural norms and human rights. This is yet another example of how investigations to identify the organizers of a crime may lead to mass arrests. In this regard, we appeal to the public, the leadership of Uzbekistan and personally to President Islam Karimov to take control of the ongoing investigation of terrorist acts and to ensure the objectivity of the investigation in order to prevent mass arrests among the population — because random and unjustified arrests will allow the real organizers of the terrorist attack to remain at large and continue their criminal acts.”

About a month after my speech I was on my way home in Kyiv when three men in camouflage uniforms jumped out of a van parked on the roadside and attacked me. They slammed me down on the pavement, twisted my arms, handcuffed me, put a bag over my head and loaded me into the van like a load of firewood. The car had no license plates and the officers did not ask for documents confirming my identity. This meant that the operation was the work of the Uzbek special services and was not being carried out lawfully.

I was brought to the pre-trial detention center of the Troyeshchynsky District police department, which was located far from the city center in Kyiv. They took the bag off my head in the interrogation room. I immediately started asking questions: Who were they, on what grounds was I detained, and why was it done so violently.

“Are you a citizen of Uzbekistan, Yusufboi Ruzimurodov?” the duty officer asked.

“Yes, but you should have known my identity when you detained me,” I replied.

“That’s a question for the men who detained you. I’m the duty officer. You are arrested on suspicion of involvement in the explosions in Tashkent.”

“That’s slander! I’m a journalist. I was persecuted in my homeland for criticizing the president and was forced to leave Uzbekistan. I’ve been living in Kyiv legally for five years now. How can I be involved if I never left Ukraine? Do you even hear yourself?!”

After I spoke, the duty officer turned to the two Asians who were standing behind me. Until then I hadn’t noticed them. One was tall and trim, about 35-38 years old; the other was a little shorter than me, athletic and younger than the first. He quickly ran up to me and struck me twice in the face. One of the blows split my lower lip and drew blood. The man told me in Uzbek to shut up. There was no doubt in my mind that these were Uzbek Federal Security Service (SBS) officers.

“That’s a barefaced lie,” I went on without taking my eyes off him. Then, turning to the duty officer, I added, “Run all the information about me. Find out everything first!”

“And who should I ask? Are there people here who know you?”

“Yes, of course. Go to the Verkhovna Rada. Ask Vyacheslav Chernovol about me!”

“Who — Chernovol? Do you mean Deputy Chernovol — in the Rukh Party?

“Yes! That’s him.”

The duty officer flinched at the words and shot a surprised look at the men standing next to him. Seeing his reaction, I continued confidently. “This is against the law, and I demand that you stop immediately! What you are doing now will be a black stain in the history of Ukraine. Think about what you are doing!”

The second SBS officer threatened me. “Shut up or you’ll make it worse for yourself.”

Just then a militia major appeared. He looked at the duty officer and shouted, “I don’t get it! What are you doing with this terrorist?”

“Terrorists are people who keep their names secret. Since I’ve been detained, none of you have identified yourselves.”

“Lock him up immediately in Cell No. 6,” he ordered the men.

***

In Cell No. 6 unpleasant news awaited me. A cellmate told me that three more detainees from Uzbekistan had been brought in earlier. Among them was a journalist identified as Muhammad Bekjon. My heart turned over. Bekjon had been detained in the apartment he rented. Together with him they took the newspaper’s courier, an activist of the group “Birlik,” Kobul Diyorov, and Nemat Sharipov, who just happened to be visiting. They were also locked up in the temporary detention center.

The four of us were taken to Boryspil Airport. They put us in handcuffs and put bags over our heads, took us on board the Uzbekistan Airways plane, and seated us in different rows. We each sat between two security officers. After takeoff, they took the bags off our heads, and we flew to Tashkent.

At the airport in Tashkent we were met by a large OMON detachment and four “especially dangerous criminals” — that is, us — were put into an ordinary bus used for people who committed misdemeanors.

In the Basement of the Ministry of Internal Affairs

The bus pulled into the courtyard of the Interior Ministry and stopped. We were taken to the duty officer's room in the basement. As soon as I crossed the threshold, two officers on either side of me began to beat me. Then the officer on duty filled out the detainee intake report, they put me on a chair and demanded that I sign it. I insisted that they let me call my relatives and refused to sign it without a lawyer. Naturally, this was not part of their plans. At that moment a man named Tokhir Ibragimov entered the room.

“What’s this?! Why did you let him sit down?” he asked the interrogators.

“He wants us to call home for him,” said one of them.

“And he wants a lawyer,'' said another.

“I'm your lawyer, understand? Sign the form — now!” Ibragimov shouted at me.

I refused. Then Ibragimov said, “He doesn't want to, so f*ck it! The witnesses will sign.”

And then he instructed the interrogators. “Don’t let him rest. Do you understand me? Just hit his feet with this side of the baton,” he said, showing the thick and serrated part of the baton. “Make him crawl.”

Torture

Two young interrogators took me to a special interrogation room. They made me take off my leather jacket and fur hat. (I never saw them again.) Then they began to torture me. They laid me down on the floor. One of them pressed my shoulders into the floor while the other knelt on my knees and beat my heels with a truncheon with all his might. I saw stars with each blow. Pain ran through my body as if I were being stabbed in the heart. I’d never felt this kind of piercing pain before in my life. Screams from the pain erupted from me. I screamed so hard that the interrogator who was hitting me stopped abruptly and looked at me.

“Why are you getting all upset? We’re just getting started. You've got it all ahead of you,” he said to me and then told his partner, “Gag his f*cking mouth.”

The other officer took a towel from the back of the chair and did what he was ordered. I couldn't scream now. I still needed to do something about the unbearable pain from the blows of the truncheon. They didn’t stop but in fact were getting harder and more painful. I wanted to scream, but since my mouth was held shut, I involuntarily jackknifed my body. When he raised the baton to hit me, my muscles tensed automatically to bear the blow. After he hit me ten times, I somehow gathered incredible strength and tossed off the man holding down my shoulders. He stood up and kicked my shoulder.

“Why are you twitching? Stay the f*ck still!”

He turned his back to his partner and sat on my chest. Then he used both hands to hold the towel over my mouth. They beat me for at least a half hour, maybe longer. Then they handed me a pen and told me to write a confession. I didn’t. They put me back on the floor and continued to beat me. They each beat me 30 or 40 times.

The first day was very hard. I felt as if I would die right there in the torture room.

Six people worked on me: two interrogators in three shifts. They took me out of the cell at any time of the day, regardless of what I was doing, often at lunchtime so that I didn't have time to eat. If they locked me in the cell for 20-30 minutes, it was not so that I could rest or eat, but for their own needs — to have something to eat and a smoke. I was tortured in this inhuman regime for two weeks. In the first days it was unbearably painful. I screamed and howled. When my mouth was covered with a towel, I spasmed convulsively in pain. And then, after three or four days, the nerves in my heels were destroyed and it stopped hurting. I could just hear the thud of the impact. When I closed my eyes, it was like the sound wasn’t coming from my body.

The excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.