Over many centuries goose was the main dish on the Christmas table in Russia and a symbol of holiday gluttony.

Duck, on the other hand, was considered an an impractical choice. What could you get out of a duck for the Christmas meal? A breast and two legs — and that’s it.

That said, duck is one of the few products that can be used to make absolutely everything: an appetizer, main course, salad, soup and even dessert (foie gras with biscuits, for example). It can be stewed, braised, roasted, boiled, steamed, and baked. Perhaps that's the reason the duck gradually took over our Christmas?

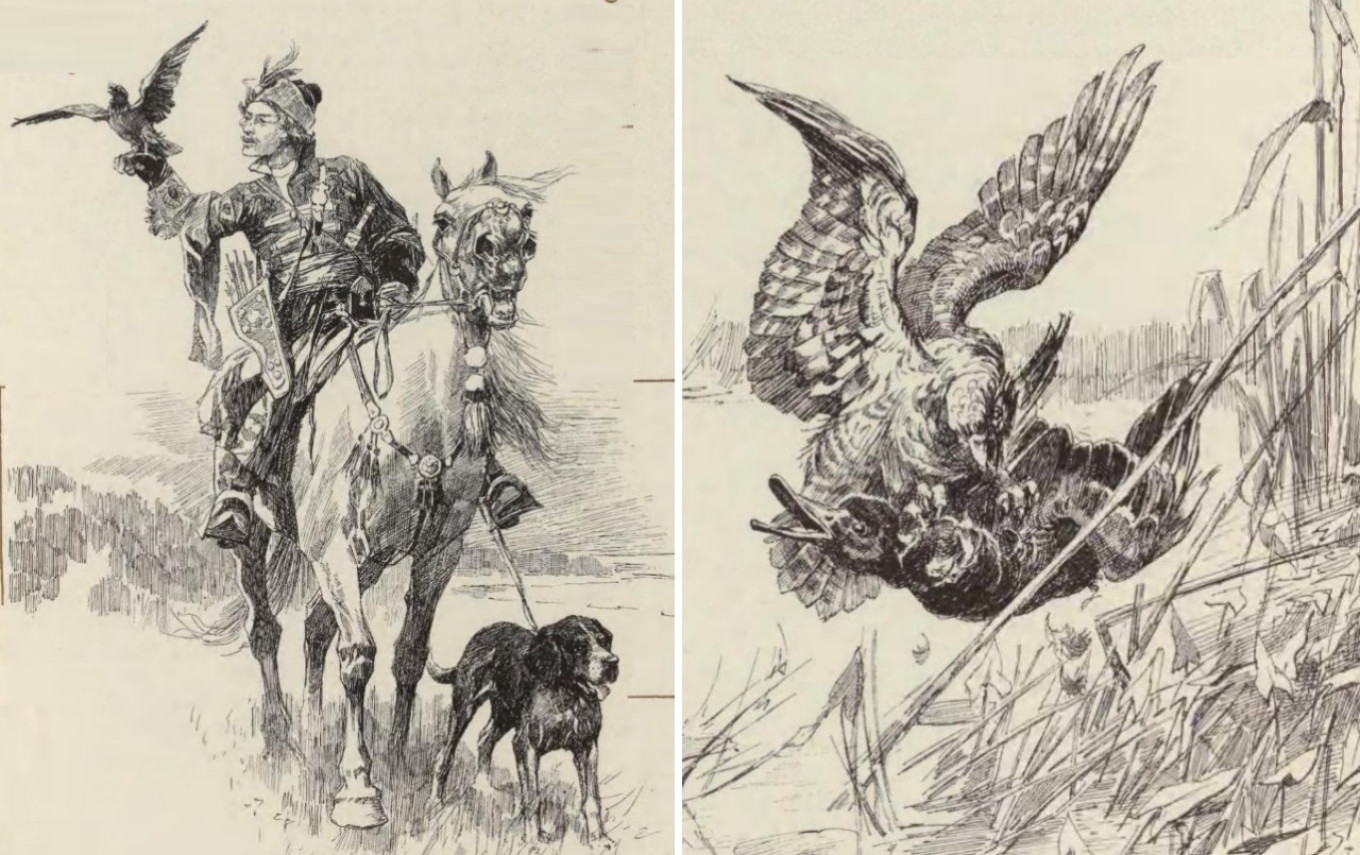

The duck situation in Russia is not straightforward. How can you determine whether a wild or domestic duck should be used in a recipe? If there is no clear instruction, then see what season the recipe is for. If it's a winter recipe, then it's not made with a wild duck. Wild ducks, unlike bustards or grouse, fly south in winter.

In fact, the “Domostroi” (1550s) does not mention duck at Christmas, although the menu lists just about every other bird in great detail:

“On the Great Feast of the Nativity of Christ it is right to serve: swans and swan giblets, roasted geese, black grouse, partridges, hazel grouse, piglet roasted on a spit, lamb in aspic, chicken bouillon, corned beef with garlic and spices, elk...”

According to the “Domostroi,” duck could be eaten “on the first day the fast is broken” (that is, Easter) and in summer (“from Peter's Day”). Why is it not eaten in the fall and winter, when, it would seem, it should be fat and tasty?

A similar situation is observed in the “Inventory of the Tsar's dishes” (1610-13). There, duck dishes are suggested for the “Great Holiday” (Easter) — duck roasted on a spit — and again for a religious holiday in August — also duck roasted on a spit. But from autumn to spring, duck is completely absent from the menu.

From all this we can safely conclude that before the 17th century in Russia, ducks were only hunted, not domesticated. It’s easy to explain — even chickens hadn’t been fully domesticated. Breeding and selection only began in the 18th century. Before that hens did not lay eggs regularly on peasant farms, and the eggs were almost half the size of today’s chicken eggs. In this context, no one even considered domesticating ducks.

So before the 17-18th centuries, there were only wild ducks — and they flew south for Christmas. They usually flew off when the surface of lakes and rivers froze over, but often there were periods of thaw and warm weather on and off for many weeks before winter set in. So freezing duck carcasses in the late fall and early winter before Christmas was a matter of chance. Peasants didn’t have icehouses, so a duck could only be kept by a rich landowner or monastery.

But why would they? Why go to all the effort when there was plenty of other game in winter: several varieties of grouse, bustards, and partridges... Although of course some people managed to serve duck during the winter months, it's wasn't a common dish on the Christmas table.

We can confirm this with a number of historical sources. For example, the traveler Paul of Aleppo, who visited Russia in 1654-56, only wrote about domestic ducks in Ukraine (which he calls the “Cossack lands”). He seems to correctly note the transitional situation with both semi-wild ducks and chickens and already fully domesticated ones: “Nothing surprised us so much as the abundance of their stock and birds, namely: chickens, geese, ducks and turkeys that can be found in great numbers in fields and forests, feeding far from towns and villages. They lay their eggs among the woods and in hidden places... As for their domestic animals and livestock, there are ten kinds of animals in every owner's house: horses, cows, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, geese, ducks, turkeys, and pigeons, for which there is room above the ceilings of the houses.” But Paul of Aleppo does not mention any ducks in the houses of Muscovy.

But Balthasar Coyett, who visited Moscow as part of the Dutch embassy in 1675-76, witnessed the transition of the duck from wild to domestic status. Passing through Totma (near Vologda), he got acquainted with village life: “When one enters the upper rooms in villages, they are full of women, children, cows, sheep, pigs, geese, ducks and chickens. But as soon as someone enters, immediately the big animals are driven outside.” So already by the end of the 17th century ducks were common in Russian villages.

Naturally, the process of domestication of the duck in Russia was not a one-step process: we will not find the year when one day there were only wild duck and the next day they were already domesticated. And of course the process occurred at different times in different regions. For example, we can see this in a letter Tsar Fyodor wrote in May 1590 to Maxim and Nikita Stroganov in the town of Sol Vychegodskaya. He wrote that he wanted to find “thirty plowmen to live in Siberia.” “And every man,” he continued, “should have three good geldings, three cows, two goats... two ducks, and a year's worth of grain.”

But again, this process was not universal. Even in the 17th century it was still easy to confuse wild and domesticated ducks. In the files of the archive of the Ministry of Justice there is a record for 1687 containing a complaint by Ivan Bocharnikov against a certain Patan Vyglazovsky, who was accused of killing a domestic duck that he thought was wild. So the domesticated duck history in Russia is not very long at all.

But to be honest, ducks are not the easiest birds to cook. They aren’t very meaty. And the legs and breast need to be cooked at different temperatures, so it takes a great deal of attention and care to roast a whole bird. Ducks have large internal cavities and a lot of fat. The special flavor of duck makes it a great addition to the holiday table, but a whole bird is not enough for more than two or three people. That's why we prefer to make duck into an appetizer. Here’s our favorite.

Duck Breast Terrine

Ingredients

- 300 g (10.5 oz) ham

- 2 whole skinless duck breasts (approx. 500 g or 1.1 lb)

- 40 ml (3 Tbsp) cognac

- 2 small garlic cloves

- 1/3 tsp thyme leaves

- 2 Tbsp meat stock

- 5 g (0.88 oz) gelatin (about ¾ of one US gelatin packet)

- 150 g (5 oz) pitted olives

- salt, freshly ground black pepper

- a few slices of raw smoked bacon

- terrine mold with lid

Instructions

- Cut the duck breast and ham into 1-cm (1/2 inch) cubes.

- Put the meat cubes in a bowl, pour in the stock, add the gelatine, season with black pepper, salt, brandy, garlic and thyme.

- Mix well; cover and leave in the refrigerator for 10-12 hours. It can be cooked immediately without marinating, but it tastes better when marinated.

- Preheat the oven to 150°C /300°F.

- Fill the terrine mold with the meat mixture and olives.

- Cover the top with bacon, press down and cover with the lid.

- Put the terrine mold in a baking dish and pour in boiling water to 1/3 from the top of the terrine.

- Carefully place in the oven.

- Cook for 1.5-2 hours.

- Take the terrine out of the oven and out of the baking dish.

- Remove the lid and cover the terrine with cling film.

- Put something hard (plastic, cardboard) on the cling film and place a weight on top.

- Let it cool and then put in the refrigerator for 24 hours.

- The next day, take the terrine out of the fridge and leave for 2 hours before serving. Serve with good bread and gherkins

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.