Russia’s unleashing of the Oreshnik experimental ballistic missile on Ukraine was a propaganda operation designed by the Kremlin, the military, and intelligence agencies to reignite fear in Kyiv and Western capitals that had grown accustomed to Moscow’s nuclear saber-rattling.

President Vladimir Putin said the military fired the Oreshnik on the city of Dnipro in response to Kyiv’s use of U.S.- and British-made long-range weapons on Russian soil.

Four Russian officials told The Moscow Times that the Oreshnik strike and its ensuing media coverage were carefully crafted with the involvement of officials, military personnel, intelligence agencies and Kremlin PR experts.

All four sources spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

"There were brainstorming sessions about how to respond and put the Americans and the British in their place for allowing Zelensky to use long-range weapons. And how to scare Berlin and other Europeans into submission," said one Russian official.

The result was a military propaganda campaign designed to exaggerate the capabilities of the Russian military-industrial complex and the might of a new weapon.

"This show, which was staged and presented to the public, consisted of several phases. The main ones were the actual Oreshnik strike, the dissemination of footage on social media, and its coverage in foreign media," another Russian official said.

The campaign involved Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova and Alexei Gromov, a high-ranking Kremlin official who oversees the Foreign Ministry and other press offices as well as controls state TV news agenda and narratives.

Gromov was reportedly the person who called Zakharova during a morning briefing with journalists and, on speakerphone, forbade her from commenting on the “ballistic missile strike on a military factory in Dnipro.”

"Some of those who were in the brainstorming sessions were particularly proud of that stunt," a Russian official said.

The campaign’s climax came when Putin threatened to strike "decision-making centers" in Kyiv with the Oreshnik at a summit of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Russia’s answer to NATO with fellow former Soviet republics.

"The summit was supposed to address member-state issues. However, the boss [Putin] essentially hijacked the public agenda and used it to threaten Zelensky's allies," an official familiar with preparations for the summit said.

"I suspect that for the other summit participants, the heads of CSTO states, this came as a surprise. They essentially became side dishes to our main course: a psychological warfare act against the West," the official added.

While Moscow had been preparing for the possibility of Ukraine being authorized to strike deep inside Russia’s borders with Western weapons, the Biden administration’s approval for Kyiv to use ATACMS missiles nevertheless alarmed the Kremlin and caught it off-guard.

ATACMS can be launched suddenly, requiring only minutes for deployment, making it possible for Ukraine to inflict significant damage on Russian military equipment, headquarters, personnel and arms depots, Pavel Aksyonov, a military analyst at BBC Russian, told The Moscow Times.

Moreover, the Biden administration's greenlighting showed that Kyiv and its Western allies still have many tools for escalation up their sleeves.

For Putin — whose army continues to slowly advance against Ukraine’s resource-strained army through the December mud of Donbas despite suffering dramatic daily losses — the options for reciprocal escalation are much more limited.

The Kremlin's threats to use nuclear weapons, which it had skillfully used for years to intimidate European politicians, are no longer as effective as they once were, with experts and Western leaders alike calling to ignore them.

This is why Kremlin spin doctors recommended launching a massive PR campaign around the Oreshnik.

However, Russia lacks a substantial stockpile of Oreshnik systems, and Putin himself admitted that the strike on Dnipro was a test.

Realistically, it would take years to mass-produce the Oreshnik given the bureaucratic inefficiencies and lagging innovation that plague Russia's defense sector, a former Russian defense engineer told The Moscow Times.

"Even relatively simple, non-missile-related projects can take five to seven years to develop," the engineer said on condition of anonymity. "This strike on Ukraine seems to have been [the Oreshnik's] first test. There wouldn't be a lot of data to justify launching it into mass production."

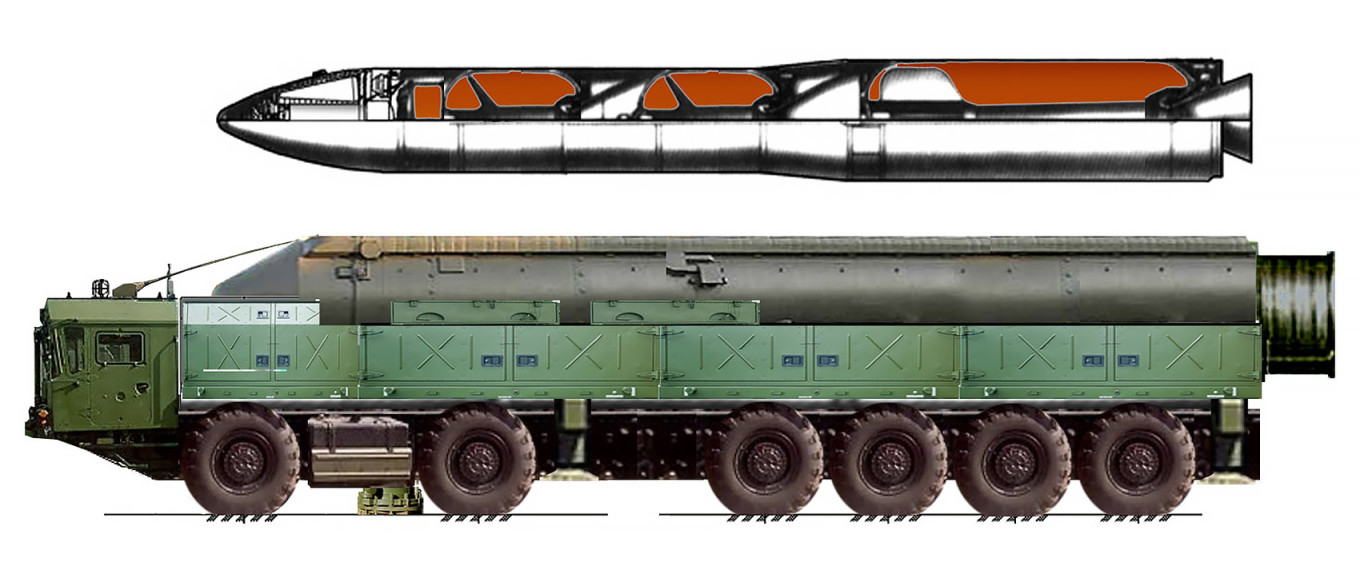

The engineer added that Russia already has missiles similar to the Oreshnik in its arsenal, such as its base model, the RS-26 Rubezh.

The engineer also suggested that deploying an experimental weapon in a real combat scenario was likely more about influencing public opinion than showcasing new military capabilities.

The Oreshnik strike, which was followed by days of commentary from Russian officials, politicians and bloggers, was nothing more than a PR stunt, military analyst Aksyonov said.

"Putin waved the nuclear stick around for too long. He needed something new. So [he brought out] the Oreshnik. It hasn’t destroyed anything, it won’t be available for the army anytime soon, but everyone is afraid," Aksyonov said.

"People thought Putin had no tools for escalation. But then came Iranian ballistic missiles, then North Korean ones, and even North Korean soldiers,” Aksyonov said. “It turned out he does have methods of escalation – but nowhere near as many as the West.”

Mack Tubridy contributed reporting to this article.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.