LVIV, Ukraine — Alisa* is on the train back to Ukraine for the first time since the full-scale invasion. She lives in Prague with her two children, and is returning to Lviv to see her mother.

“It’s not safe here,” she shrugs. “But nowhere is safe."

Marta* from Cherniv looks out at the flat landscape — fields of spent wheat, birch trees and industrial wagons that scarcely change after we pass the gold-domed church at the Ukrainian border.

“Poland, Ukraine, Czechia: The countryside may look the same,” says Marta, “but your own land feels different.”

Three trains a day run from Przemysl on the Polish border to Lviv, and onward to Kyiv and towns in Ukraine’s war-torn east.

Lviv is humming with the pre-Christmas atmosphere of any European city in late November. A woman is carrying a giant advent calendar of German beer cans. Frank Sinatra croons in a café selling the city’s signature croissants, while local teenagers are charging their phones on a generator. The first snowflakes are falling.

An air alert in the middle of the day is met with a shrug. As the siren wails, an app on my cellphone booms: “Your overconfidence is your weakness! Make your way to the nearest shelter.” But the lobby is still full of people sipping cappuccinos and outside the streets are bustling.

Yet a sense of unease can be felt beneath the surface. Sofia, a 19-year-old economics student, is worried about Russia’s new Oreshnik ballistic missile, which hit Dnipro the previous day.

“They say it breaks into six pieces. Now I’m six times as scared,” she says.

Sofia says she hopes the war will end before her 24-year-old brother is mobilized into the army. The age of conscription in Ukraine is 25, and men between the ages of 18 and 60 are barred from leaving the country under martial law.

Between 7:00 p.m. and the beginning of curfew at midnight, Lviv’s bars come alive. Foreign volunteers who are in town to build drones, cook soup for soldiers and walk stray dogs mix with locals as well as Ukrainians from other regions who come here to unwind.

Anton, a police officer from a suburb of Kyiv, is here for the weekend with his wife. They have many questions about life outside the warzone.

I ask Anton what he thinks of the capture of military-age men by the unmarked recruitment vans that patrol the streets at night.

“I think it’s cruel,” he says, his voice dropping to a whisper. “But I don’t know that there is an alternative. Not at this time.”

Twenty-one-year-old Denis from Odesa and his friend Yasha from Kharkiv are drinking in the same bar. Yasha, who has bushy eyebrows and a clownish sense of humor, is enrolled at a local university but says he never goes to class.

“When the war started, my mum and sister crossed the border into Romania. My dad and I came here,” Denis says. “We joined the National Guard, but I haven’t had to fight yet.”

He frowns. “I get scared that I am not enough of a patriot. I want to help my country. But I don’t want to die.”

The moment passes, and Denis goes back to showing off his new tattoo, which reads CHANEL NO.5.

I spend the next day at Lviv’s central train station, a crossroad for the various organizations helping arrivals from eastern Ukraine. It seems busy to me, with groups of soldiers in transit as well as families. The many who are wounded are being helped into taxis to nearby hospitals.

Arthur, an aid worker from the Ptaha NGO, tells me the station is much quieter than at the beginning of the war, despite heavy bombardment now taking place at the other end of the line.

“We used to help 20 people a day, now sometimes only one or two,” he says. Psychotherapist Valentyn Bordun says Ptaha has met as many as 700,000 people at the train station since February 2022. The team is busy wrapping hundreds of St. Nicholas’ Day gifts for displaced children.

Arthur believes the reduced flow of people is partly due to the Ukrainian government cutting funding for refugees who spend more than 30 consecutive days abroad. There is an assumption that the government in the second country will start paying benefits.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” Valentyn explains. “Sometimes refugees go to Poland, use up the 30-day window and all their money, and don’t manage to get Polish benefits or a job. And so they come back to Ukraine even poorer.”

Ukraine offers a monthly stipend of 2,000 hryvnia ($48) for internally displaced people (IDPs), with 3,000 hryvnia ($72) for those with disabilities. It’s enough to live on for a few days. The government says it plans to make payments more efficient in 2025.

We go to meet the midday train arriving from the frontline city of Zaporizhzhia. An elderly man on crutches clambers down from the high steps of the Soviet-era wagon and makes his way through the station. A woman who has arranged to meet the volunteers before traveling onward to Germany receives medical aid, but is surprised to learn that she will have to cover the cost of her journey herself.

A man approaches the volunteers in the station, chattering excitedly in Russian. “My name is Stepan, I’m 70 years old. I came here from Kherson. I left my family behind, there was bombing every day —”

“Sorry,” a volunteer interrupts, “There is not enough money. And the center downstairs is for women and children.” He gives him directions into town.

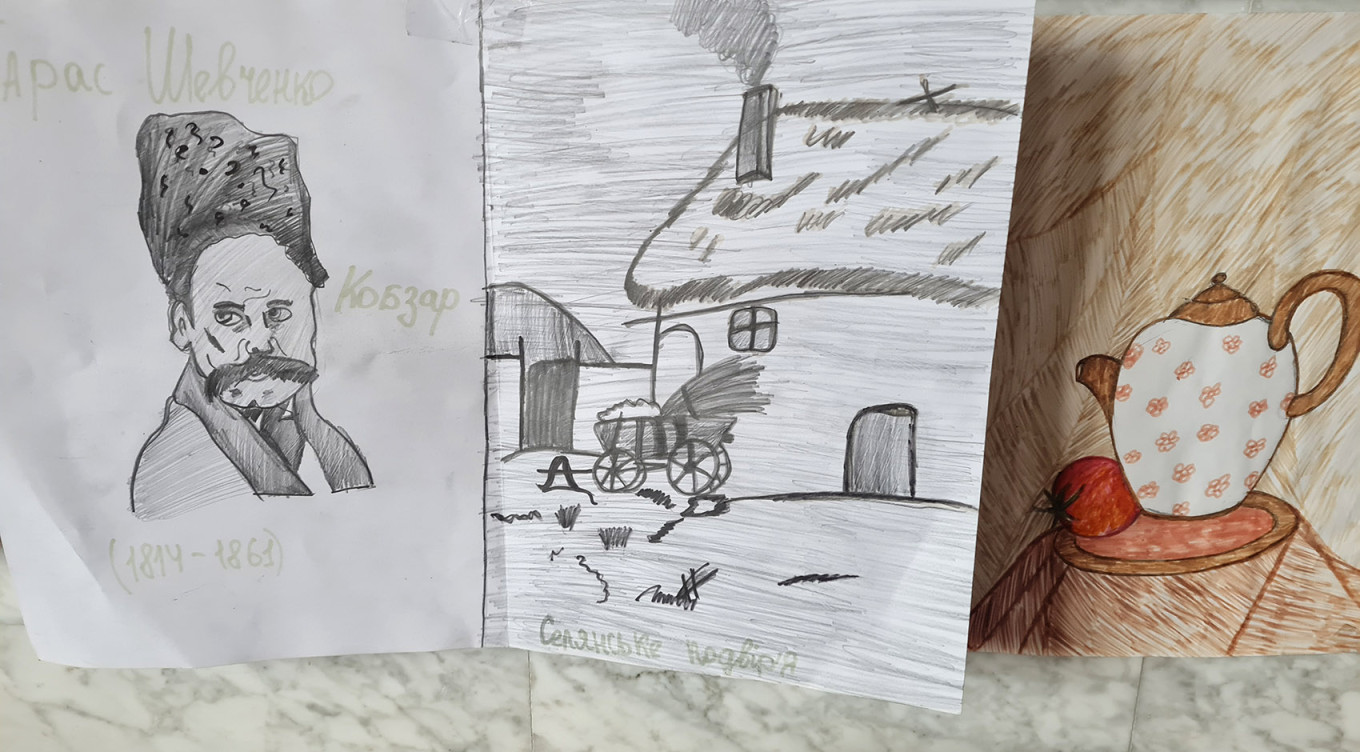

At the center for families, run by Unicef’s Spilno program, children are drawing pictures and making bracelets. A girl is riding a toy motorbike, crashing into her friends on purpose. Her pregnant mother is sleeping.

“The hardest day we had here was in July, when we had to go to the shelter for six hours,” says a worker from Spilno, who grew up in Lviv. “And sometimes it is hard hearing what people have been through after their homes were destroyed. But I like working with the kids, they bring me joy.”

Not everyone at the train station is heading west: Arthur notes that 100,000 people have returned to Russian-occupied areas of the Donbas since fleeing at the start of the war.

He says the Ukrainian government should be offering more money to people from territories that Russia captured early in the full-scale invasion. IDPs from the industrial, largely Russian-speaking regions of eastern Ukraine often struggle to find work in western Ukraine due to language barriers and a lack of transferable skills.

“People hear that the Russian authorities are rebuilding things, and they go back,” he says. Russia has invested heavily in propaganda to promote the reconstruction of Mariupol, a city it razed to the ground.

Some of those working with displaced people in Lviv are themselves former IDPs.

I meet Alex from Kharkiv, who founded the International Volunteers Center at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Like many who settled in western Ukraine after evacuation, he doesn’t see himself returning. The rest of his family are scattered across Europe.

“There are only graves left there for me now,” he said.

He pauses to reconsider the question of return.

“It depends,” he says. “Say the war were to end tomorrow, and the foreign businesses trusted us enough to come back, if there was American reconstruction. Then I might go back. But I’m used to Lviv now. Suppose the war takes another five years? I will already have spent a quarter of my life as a refugee.”

I ask Alex what terms Ukraine would accept to win the war.

After a long silence in which he looks as if he is about to cry, he finally answers: “Security guarantees, sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

*Names have been changed at the individuals’ request.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.